Figure 4: Each country’s log2 enrichment (LOE) and its 95% confidence interval (left),

and the absolute difference between observed (triangle) and expected (circle) number of honors (right).

Positive value of LOE indicates a higher proportion of honorees affiliated with that country compared to authors.

Countries are ordered based on the proportion of authorships in the field.

@@ -333,31 +352,31 @@ Discussion

The implication would be that scientific societies exist to reflect what the field could be, not just what it is.

However, we are limited to measuring the field as it is.

Furthermore, authorships, which we use to assess the field’s composition, are also affected by systemic barriers to participation.

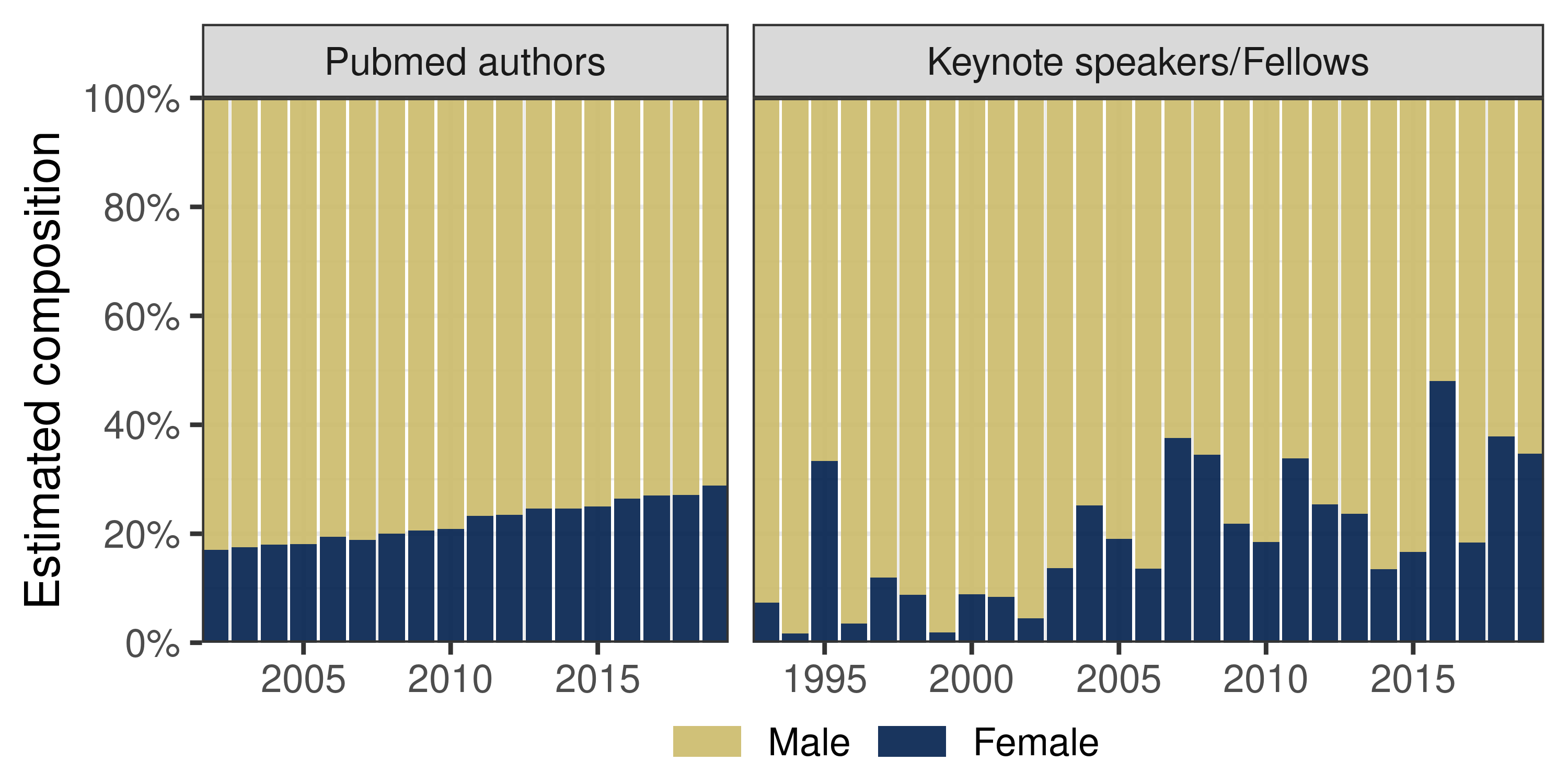

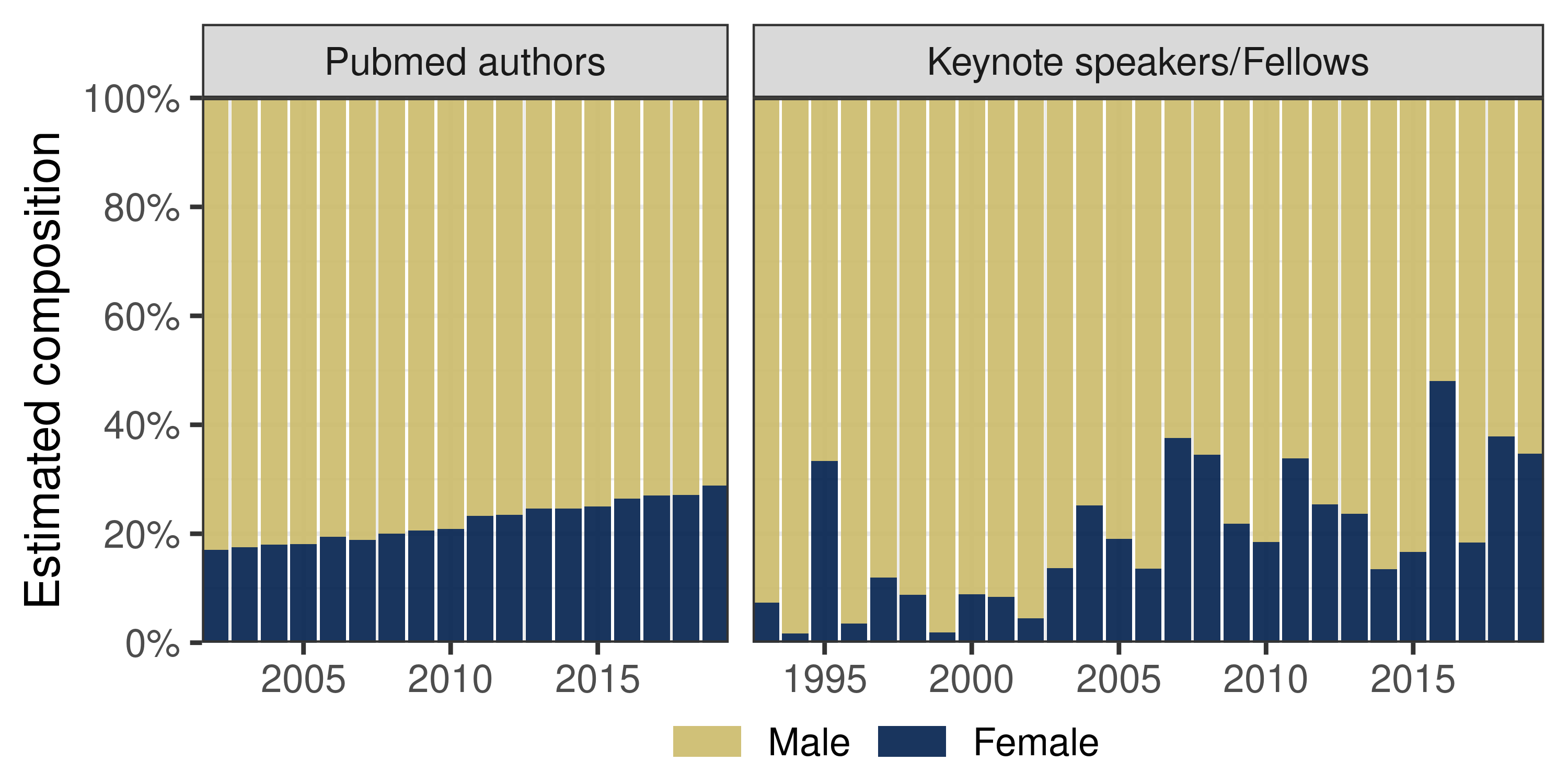

-We estimated the composition of the field using last author status, but in neuroscience (Shen et al., 2018) and other disciplines (Holman et al., 2018), women are underrepresented in this position.

+We estimated the composition of the field using last author status, but in neuroscience (Shen et al., 2018) and other disciplines (Holman et al., 2018), women are underrepresented in this position.

Such an effect would cause us to underestimate the number of women in the field.

-Similarly, other studies have showed that underrepresented groups are less likely to be last authors (Marschke et al., 2018), and Hispanic and Black scientists were underrepresented in academic publishing in general (Hopkins et al., 2012).

+Similarly, other studies have showed that underrepresented groups are less likely to be last authors (Marschke et al., 2018), and Hispanic and Black scientists were underrepresented in academic publishing in general (Hopkins et al., 2012).

Thus, systemic barriers that reduce representation within our estimation of the field would reduce apparent disparities in honor distributions as long as those systemic barriers did not also have a particular influence on the honoree selection process as well.

An important ethical question to ask when measuring representation is what the right level of representation is.

Societies should examine their processes to determine whether the process of selecting honorees should be equal or equitable.

For example, we found similar representation of women between authors and honorees, which suggests honoree diversity is similar to that of authors and that there may be equality during the honoree selection process.

However, if fewer women are in the field because of systemic factors that inhibit their participation, reaching equality is not equivalent to reaching equity.

-In addition to holding fewer corresponding authorship positions, on average, female scientists of different disciplines are cited less often (Dworkin et al., 2020), invited by journals to submit papers less often (Holman et al., 2018), suggested as reviewers less often (Lerback and Hanson, 2017), and receive significantly worse review scores (Fox and Paine, 2019).

-Meanwhile, a review of women’s underrepresentation in math-intensive fields argued that today’s underrepresentation is not explained by historic forms of discrimination but factors surrounding fertility decisions and lifestyle choices, whether freely made or constrained by biology and society (Ceci and Williams, 2011).

-A recent analysis of gender inequality across different disciplines showed that, although both gender groups have equivalent annual productivity, women scientists have higher dropout rates throughout their scientific careers (Huang et al., 2020).

+In addition to holding fewer corresponding authorship positions, on average, female scientists of different disciplines are cited less often Larivière et al. (2013), invited by journals to submit papers less often (Holman et al., 2018), suggested as reviewers less often (Lerback and Hanson, 2017), and receive significantly worse review scores (Fox and Paine, 2019).

+Meanwhile, a review of women’s underrepresentation in math-intensive fields argued that today’s underrepresentation is not explained by historic forms of discrimination but factors surrounding fertility decisions and lifestyle choices, whether freely made or constrained by biology and society (Ceci and Williams, 2011).

+A recent analysis of gender inequality across different disciplines showed that, although both gender groups have equivalent annual productivity, women scientists have higher dropout rates throughout their scientific careers (Huang et al., 2020).

Therefore, although we found that ISCB’s honorees and keynote speakers appear to have similar gender proportion to the field as a whole, the gender proportions have not reached parity.

To the extent that this gap is due to systemic barriers, the process may have reached equality but not equity.

It is also possible to have processes that reach neither equality nor equity.

We find that honorees include significantly fewer people of color than the field as a whole, and Asian scientists are dramatically underrepresented among honorees.

Because invitation and honor patterns could be driven by biases associated with name groups, geography, or other factors, we cross-referenced name group predictions with author affiliations to disentangle the relationship between geographic regions, name groups and invitation probabilities.

We found that disparities persisted even within the group of honorees with a US affiliation.

-Societies’ honoree selection process failing to reflect the diversity of the field can play a part in why minoritized scientists’ innovations are discounted (Hofstra et al., 2020).

+Societies’ honoree selection process failing to reflect the diversity of the field can play a part in why minoritized scientists’ innovations are discounted (Hofstra et al., 2020).

Although we estimate the fraction of non-White and non-Asian authors to be relatively similar to the estimated honoree rate, we note that both are represented at levels substantially lower than in the US population.

-Societies, both through their honorees and the individuals who deliver keynotes at their meetings, can play a positive role in improving the presence of female STEM role models, which can boost young students’ interests in STEM (Ceci and Williams, 2011) and, for example, lead to higher persistence for undergraduate women in geoscience (Hernandez et al., 2018).

-Efforts are underway to create Wikipedia entries for more female (Wade and Zaringhalam, 2018) and black, Asian, and minority scientists (O’Reilly, 2019), which can help early-career scientists identify role models.

+

Societies, both through their honorees and the individuals who deliver keynotes at their meetings, can play a positive role in improving the presence of female STEM role models, which can boost young students’ interests in STEM (Ceci and Williams, 2011) and, for example, lead to higher persistence for undergraduate women in geoscience (Hernandez et al., 2018).

+Efforts are underway to create Wikipedia entries for more female (Wade and Zaringhalam, 2018) and black, Asian, and minority scientists (O’Reilly, 2019), which can help early-career scientists identify role models.

Societies can contribute toward equity if they design policies to honor scientists in ways that counter these biases such as ensuring diversity in the selection committees.

The central role that scientists play in evaluating each other and each other’s findings makes equity critical.

Even many nominally objective methods of assessing excellence (e.g., h-index, grant funding obtained, number of high-impact peer-reviewed publications, and total number of peer-reviewed publications) are subject to the bias of peers during review.

-These could be affected by explicit biases, implicit biases, or pernicious biases in which a reviewer might consider a path of inquiry, as opposed to an individual, to be more or less meritorious based on the reviewer’s own background (Hoppe et al., 2019).

+These could be affected by explicit biases, implicit biases, or pernicious biases in which a reviewer might consider a path of inquiry, as opposed to an individual, to be more or less meritorious based on the reviewer’s own background Murray et al. (2019).

Our efforts to measure the diversity of honorees in an international society suggests that, while a focus on gender parity may be improving some aspects of diversity among honorees, contributions from scientists of color are underrecognized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation whose support makes the study possible (GBMF4552 to D.S.H. and GBMF4552 to C.S.G.).

@@ -465,11 +484,11 @@

Data and Code Availability

Our Wikipedia name dataset is dedicated to the public domain under CC0 License at https://github.com/greenelab/wiki-nationality-estimate, with source code to construct the dataset available under a BSD 3-Clause License.

All original code has been deposited at Zenodo and is publicly available as of the date of publication.

DOIs are listed in the key resources table.

-Specifically, our analysis of authors and ISCB-associated honorees is available under CC BY 4.0 at https://github.com/greenelab/iscb-diversity, with source code also distributed under a BSD 3-Clause License (Le et al., 2021).

+Specifically, our analysis of authors and ISCB-associated honorees is available under CC BY 4.0 at https://github.com/greenelab/iscb-diversity, with source code also distributed under a BSD 3-Clause License (Le et al., 2021).

Rendered Python and R notebooks from this repository are browsable at greenelab.github.io/iscb-diversity.

Our analysis of PubMed, PubMed Central, and author names relies on the Python pubmedpy package, developed as part of this project and available under a Blue Oak Model License 1.0 at https://github.com/dhimmel/pubmedpy and on PyPI.

No additional information is required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper.

-This manuscript was written openly on GitHub at github.com/greenelab/iscb-diversity-manuscript using Manubot (Himmelstein et al., 2019).

+

This manuscript was written openly on GitHub at github.com/greenelab/iscb-diversity-manuscript using Manubot (Himmelstein et al., 2019).

The Manubot HTML version is available under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) License at greenelab.github.io/iscb-diversity-manuscript.

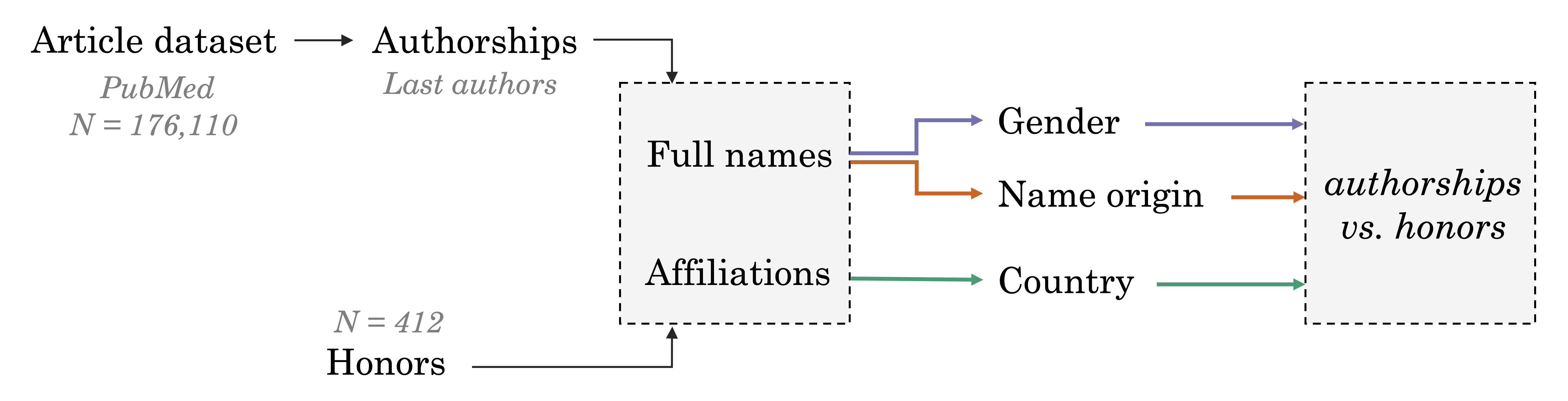

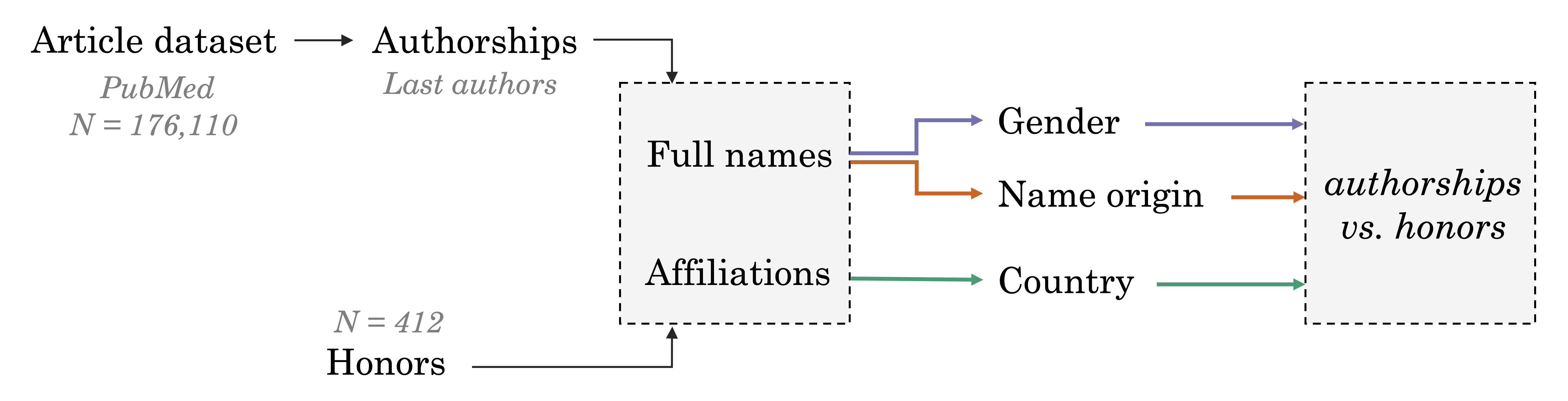

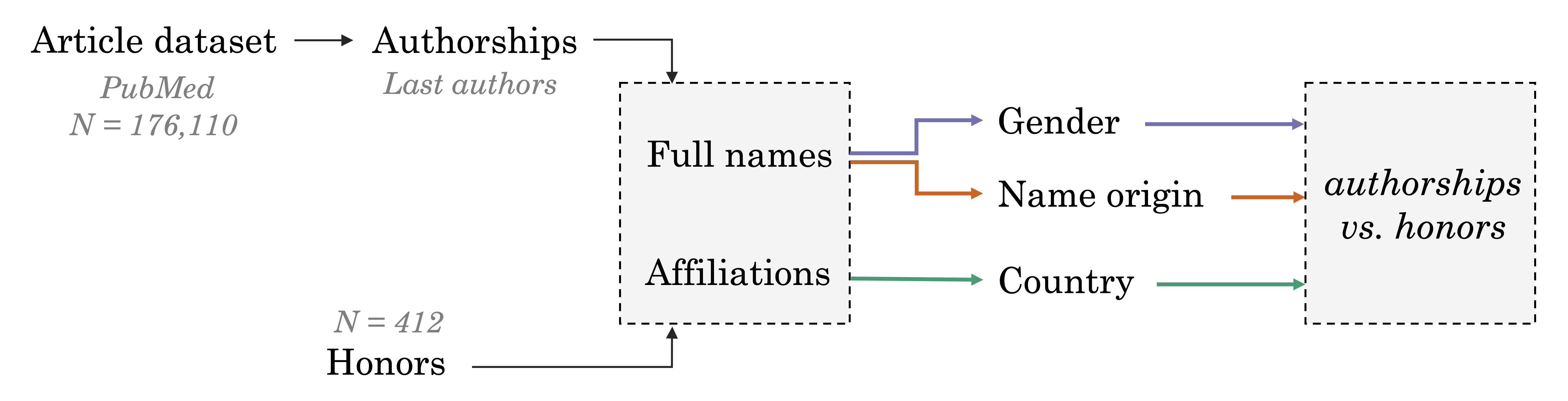

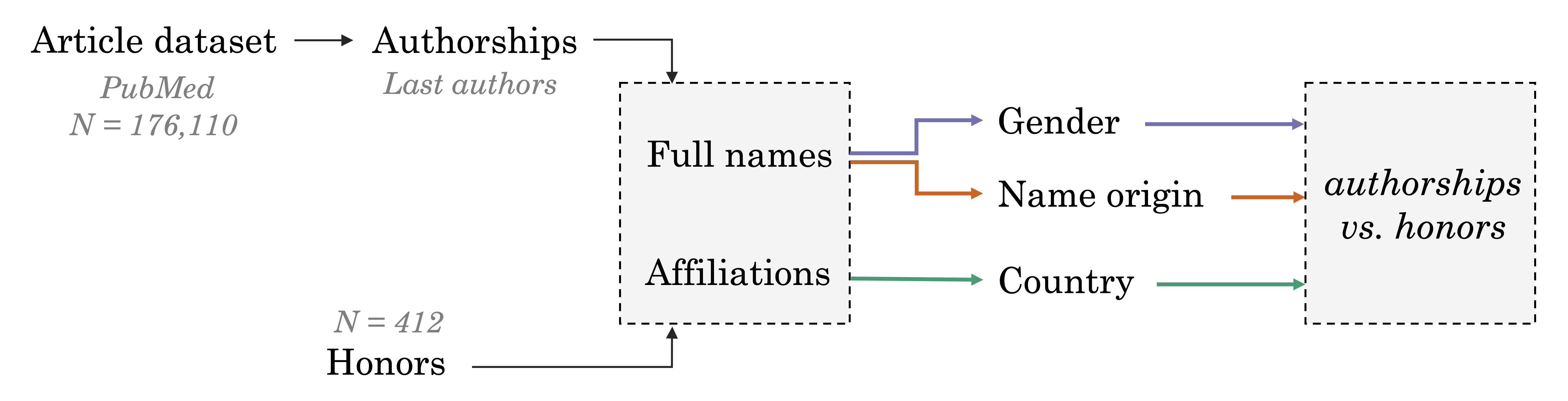

Method details

Honoree Curation

@@ -528,7 +547,7 @@ Countries of Affiliations

Because we could not find affiliations for the 1997 and 1998 RECOMB keynote speakers’ listed for these years, they were left blank.

If an author or speaker had more than one affiliation, each was inversely weighted by the number of affiliations that individual had.

Estimation of Gender

-We predicted the gender of honorees and authors using the https://genderize.io API, which was trained on over 100 million name-gender pairings collected from the web and is one of the three widely-used gender inference services (Santamaría and Mihaljević, 2018).

+

We predicted the gender of honorees and authors using the https://genderize.io API, which was trained on over 100 million name-gender pairings collected from the web and is one of the three widely-used gender inference services (Santamaría and Mihaljević, 2018).

We used author and honoree first names to retrieve predictions from genderize.io.

The predictions represent the probability of an honoree or author being male or female.

We used the estimated probabilities and did not convert to a hard group assignment.

@@ -542,10 +561,10 @@

Estimation of Gender

Of the remaining authors, genderize.io failed to predict gender for 10,003 of these fore names.

We note that approximately 42% of these NA predictions are hyphenated names, which is likely because they are more unique and thus are more difficult to find predictions for.

-This bias of NA predictions toward non-English names has been previously observed (Wais, 2016) and may have a minor influence on the final estimate of gender compositions.

+This bias of NA predictions toward non-English names has been previously observed (Wais, 2016) and may have a minor influence on the final estimate of gender compositions.

Estimation of Name Origin Groups

We developed a model to predict geographical origins of names.

-The existing Python package ethnicolr (Sood and Laohaprapanon, 2018) produces reasonable predictions, but its international representation in the data curated from Wikipedia in 2009 (Ambekar et al., 2009) is still limited.

+The existing Python package ethnicolr (Sood and Laohaprapanon, 2018) produces reasonable predictions, but its international representation in the data curated from Wikipedia in 2009 (Ambekar et al., 2009) is still limited.

For instance, 76% of the names in ethnicolr’s Wikipedia dataset are European in origin.

To address these limitations in ethnicolr, we built a similar classifier, a Long Short-term Memory (LSTM) neural network, to infer the region of origin from patterns in the sequences of letters in full names.

We applied this model on an updated, approximately 4.5 times larger training dataset called Wiki2019 (described below).

@@ -565,10 +584,10 @@

Estimation of Name Origin Groups

We used regular expressions to parse out the person’s name from this structure and checked that the expression after “is a” matched a list of nationalities.

We were able to define a name and nationality for 708,493 people by using the union of these strategies.

This process produced country labels that were more fine-grained than the broader patterns that we sought to examine among honorees and authors.

-We initially grouped names by continent, but later decided to model our categorization after the hierarchical taxonomy used by NamePrism (Ye et al., 2017).

+We initially grouped names by continent, but later decided to model our categorization after the hierarchical taxonomy used by NamePrism (Ye et al., 2017).

The NamePrism taxonomy was derived from name-country pairs by producing an embedding of names by Twitter contact patterns and then grouping countries using the similarity of names from those countries.

The countries associated with each grouping are shown in supplementary figure S1.

-NamePrism excluded the US, Canada and Australia because these countries have been populated by a mix of immigrant groups (Ye et al., 2017).

+NamePrism excluded the US, Canada and Australia because these countries have been populated by a mix of immigrant groups (Ye et al., 2017).

In an earlier version of this manuscript, we also used category names derived from NamePrism, but a reader pointed out the titles of the groupings were problematic;

@@ -581,7 +600,7 @@

P

Table 1 shows the size of the training set for each of the name origin groups as well as a few examples of PubMed author names that had at least 90% prediction probability in that group.

We refer to this dataset as Wiki2019 (available online in annotated_names.tsv).

-

+

Table 1: Predicting name-origin groups of names trained on Wikipedia’s living people.

The table lists the 10 groups and the number of living people for each region that the LSTM was trained on.

Example names shows actual author names that received a high prediction for each region.

@@ -679,7 +698,7 @@ Affiliation Analysis

For each country, we computed the expected number of honorees by multiplying the proportion of authors whose affiliations were in that country with the total number of honorees.

We then performed an enrichment analysis to examine the difference in country affiliation proportions between ISCB honorees and field-specific last authors.

We calculated each country’s enrichment by dividing the observed proportion of honorees by the expected proportion of honorees.

-The 95% confidence interval of the log2 enrichment was estimated using the Poisson model method (Sahai and Khurshid, 1996).

+The 95% confidence interval of the log2 enrichment was estimated using the Poisson model method (Sahai and Khurshid, 1996).

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the levels of representation by performing the following logistic regression of the group of scientists on each name’s prediction probability while controlling for year:

\[g = \beta_0 + \beta_1 prob + \beta_2 y + \epsilon.\]

@@ -697,13 +716,13 @@

Iterative Research Process

Parallel analyses for the other versions are available in supplementary figure S3.

In our first version of the analysis pipeline, we sought to characterize the distribution of authorships in the field using field-specific journals.

This resulted in an analysis set of 29,755 authorships.

-We also examined corresponding authors, as we considered that senior authors may occasionally occupy a different position (Larivière et al., 2016), and only fell back to last authors in cases where corresponding author annotations were unavailable.

+We also examined corresponding authors, as we considered that senior authors may occasionally occupy a different position (Larivière et al., 2016), and only fell back to last authors in cases where corresponding author annotations were unavailable.

In the next version of the analysis, we extended the analysis to all 176,110 computational biology PubMed articles, substantially increasing the sample size.

We also extracted names of last authors instead of other potential selections to better capture the honoree population.

Our assumption was that, among the authors of a specific paper, the last author (often research advisors) would be most likely to be invited for a keynote or honored as a fellow.

Also, the availability of information on corresponding authors was limited, and extracting last author became a more consistent approach.

In version 3, instead of weighting all articles equally as in the earlier versions, we used citation count to weight articles to control for the differential impact of research contributions.

-Using citation counts has key limitations: female scientists of different disciplines are cited less often than their male counterparts (Caplar et al., 2017; Dworkin et al., 2020; Fox and Paine, 2019).

+Using citation counts has key limitations: female scientists of different disciplines are cited less often than their male counterparts (Caplar et al., 2017; Dworkin et al., 2020; Fox and Paine, 2019).

Furthermore, the act of being honored, particularly with a keynote at an international meeting, could lead to work being more recognized and cited, which would reverse the arrow of causality.

In version 4, we returned to the equal weight for all articles.

Finally, in all versions of the analysis, rather than applying a hard assignment for each prediction, we analyzed the raw prediction probability values to capture the uncertainty of the prediction model.

@@ -711,120 +730,120 @@

Iterative Research Process

Examining the literature with and without citation weighting, we learned that disparities exist and these disparities are large enough to overcome existing disparities in citation patterns.

References

-

-

-

Ambekar, A., Ward, C., Mohammed, J., Male, S., and Skiena, S. (2009). Name-ethnicity classification from open sources. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

+

+

+(2011). Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC).

-

-

Caplar, N., Tacchella, S., and Birrer, S. (2017). Quantitative evaluation of gender bias in astronomical publications from citation counts. Nature Astronomy 1, 0141.

+

+(2015). Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC).

-

-

Casadevall, A., and Handelsman, J. (2014). The Presence of Female Conveners Correlates with a Higher Proportion of Female Speakers at Scientific Symposia. mBio 5.

+

+(2016). Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC).

-

-

Ceci, S.J., and Williams, W.M. (2011). Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 3157–3162.

+

+Ambekar, A., Ward, C., Mohammed, J., Male, S., and Skiena, S. (2009). Name-ethnicity classification from open sources. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

-

-

Dworkin, J.D., Linn, K.A., Teich, E.G., Zurn, P., Shinohara, R.T., and Bassett, D.S. (2020). The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists (arXiv).

+

+Caplar, N., Tacchella, S., and Birrer, S. (2017). Quantitative evaluation of gender bias in astronomical publications from citation counts. Nature Astronomy 1, 0141.

-

-

Fox, C.W., and Paine, C.E.T. (2019). Gender differences in peer review outcomes and manuscript impact at six journals of ecology and evolution. Ecology and Evolution 9, 3599–3619.

+

+Casadevall, A., and Handelsman, J. (2014). The Presence of Female Conveners Correlates with a Higher Proportion of Female Speakers at Scientific Symposia. mBio 5.

-

-

Ginther, D.K., Schaffer, W.T., Schnell, J., Masimore, B., Liu, F., Haak, L.L., and Kington, R. (2011). Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards. Science 333, 1015–1019.

+

+Ceci, S.J., and Williams, W.M. (2011). Understanding current causes of women's underrepresentation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 3157–3162.

-

-

Ginther, D.K., Kahn, S., and Schaffer, W.T. (2016). Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 Research Awards. Academic Medicine 91, 1098–1107.

+

+Dworkin, J.D., Linn, K.A., Teich, E.G., Zurn, P., Shinohara, R.T., and Bassett, D.S. (2020). The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists (arXiv).

-

-

Hernandez, P.R., Bloodhart, B., Adams, A.S., Barnes, R.T., Burt, M., Clinton, S.M., Du, W., Godfrey, E., Henderson, H., Pollack, I.B., et al. (2018). Role modeling is a viable retention strategy for undergraduate women in the geosciences. Geosphere.

+

+Fox, C.W., and Paine, C.E.T. (2019). Gender differences in peer review outcomes and manuscript impact at six journals of ecology and evolution. Ecology and Evolution 9, 3599–3619.

-

-

Himmelstein, D.S., Rubinetti, V., Slochower, D.R., Hu, D., Malladi, V.S., Greene, C.S., and Gitter, A. (2019). Open collaborative writing with Manubot. PLOS Computational Biology 15, e1007128.

+

+Ginther, D.K., Schaffer, W.T., Schnell, J., Masimore, B., Liu, F., Haak, L.L., and Kington, R. (2011). Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards. Science 333, 1015–1019.

-

-

Hofstra, B., Kulkarni, V.V., Munoz-Najar Galvez, S., He, B., Jurafsky, D., and McFarland, D.A. (2020). The Diversity–Innovation Paradox in Science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 9284–9291.

+

+Ginther, D.K., Kahn, S., and Schaffer, W.T. (2016). Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 Research Awards. Academic Medicine 91, 1098–1107.

-

-

Holman, L., Stuart-Fox, D., and Hauser, C.E. (2018). The gender gap in science: How long until women are equally represented? PLOS Biology 16, e2004956.

+

+Hernandez, P.R., Bloodhart, B., Adams, A.S., Barnes, R.T., Burt, M., Clinton, S.M., Du, W., Godfrey, E., Henderson, H., Pollack, I.B., et al. (2018). Role modeling is a viable retention strategy for undergraduate women in the geosciences. Geosphere.

-

-

Hopkins, A.L., Jawitz, J.W., McCarty, C., Goldman, A., and Basu, N.B. (2012). Disparities in publication patterns by gender, race and ethnicity based on a survey of a random sample of authors. Scientometrics 96, 515–534.

+

+Himmelstein, D.S., Rubinetti, V., Slochower, D.R., Hu, D., Malladi, V.S., Greene, C.S., and Gitter, A. (2019). Open collaborative writing with Manubot. PLOS Computational Biology 15, e1007128.

-

-

Hoppe, T.A., Litovitz, A., Willis, K.A., Meseroll, R.A., Perkins, M.J., Hutchins, B.I., Davis, A.F., Lauer, M.S., Valantine, H.A., Anderson, J.M., et al. (2019). Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Science Advances 5, eaaw7238.

+

+Hofstra, B., Kulkarni, V.V., Munoz-Najar Galvez, S., He, B., Jurafsky, D., and McFarland, D.A. (2020). The Diversity–Innovation Paradox in Science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 9284–9291.

-

-

Huang, J., Gates, A.J., Sinatra, R., and Barabási, A.-L. (2020). Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 4609–4616.

+

+Holman, L., Stuart-Fox, D., and Hauser, C.E. (2018). The gender gap in science: How long until women are equally represented? PLOS Biology 16, e2004956.

-

-

Klein, R.S., Voskuhl, R., Segal, B.M., Dittel, B.N., Lane, T.E., Bethea, J.R., Carson, M.J., Colton, C., Rosi, S., Anderson, A., et al. (2017). Speaking out about gender imbalance in invited speakers improves diversity. Nature Immunology 18, 475–478.

+

+Hopkins, A.L., Jawitz, J.W., McCarty, C., Goldman, A., and Basu, N.B. (2012). Disparities in publication patterns by gender, race and ethnicity based on a survey of a random sample of authors. Scientometrics 96, 515–534.

-

-

Langin, K. (2019). How scientists are fighting against gender bias in conference speaker lineups. Science.

+

+Hoppe, T.A., Litovitz, A., Willis, K.A., Meseroll, R.A., Perkins, M.J., Hutchins, B.I., Davis, A.F., Lauer, M.S., Valantine, H.A., Anderson, J.M., et al. (2019). Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Science Advances 5, eaaw7238.

-

-

Larivière, V., Ni, C., Gingras, Y., Cronin, B., and Sugimoto, C.R. (2013). Bibliometrics: global gender disparities in science. Nature 504, 211–213.

+

+Huang, J., Gates, A.J., Sinatra, R., and Barabási, A.-L. (2020). Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 4609–4616.

-

-

Larivière, V., Desrochers, N., Macaluso, B., Mongeon, P., Paul-Hus, A., and Sugimoto, C.R. (2016). Contributorship and division of labor in knowledge production. Social Studies of Science 46, 417–435.

+

+Klein, R.S., Voskuhl, R., Segal, B.M., Dittel, B.N., Lane, T.E., Bethea, J.R., Carson, M.J., Colton, C., Rosi, S., Anderson, A., et al. (2017). Speaking out about gender imbalance in invited speakers improves diversity. Nature Immunology 18, 475–478.

-

-

Le, T., Himmelstein, D., and Greene, C. (2021). greenelab/iscb-diversity: ISCB analysis v4.0 release (Zenodo).

+

+Langin, K. (2019). How scientists are fighting against gender bias in conference speaker lineups. Science.

-

-

Lerback, J., and Hanson, B. (2017). Journals invite too few women to referee. Nature 541, 455–457.

+

+Larivière, V., Ni, C., Gingras, Y., Cronin, B., and Sugimoto, C.R. (2013). Bibliometrics: global gender disparities in science. Nature 504, 211–213.

-

-

Marschke, G., Nunez, A., Weinberg, B.A., and Yu, H. (2018). Last Place? The Intersection of Ethnicity, Gender, and Race in Biomedical Authorship. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108, 222–227.

+

+Larivière, V., Desrochers, N., Macaluso, B., Mongeon, P., Paul-Hus, A., and Sugimoto, C.R. (2016). Contributorship and division of labor in knowledge production. Social Studies of Science 46, 417–435.

-

-

Martin, G. (2015). Addressing the underrepresentation of women in mathematics conferences (arXiv).

+

+Le, T., Himmelstein, D., and Greene, C. (2021). greenelab/iscb-diversity: ISCB analysis v4.0 release (Zenodo).

-

-

Martin, J.L. (2014). Ten Simple Rules to Achieve Conference Speaker Gender Balance. PLoS Computational Biology 10, e1003903.

+

+Lerback, J., and Hanson, B. (2017). Journals invite too few women to referee. Nature 541, 455–457.

-

-

Murray, D., Siler, K., Larivière, V., Chan, W.M., Collings, A.M., Raymond, J., and Sugimoto, C.R. (2019). Author-Reviewer Homophily in Peer Review. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

+

+Marschke, G., Nunez, A., Weinberg, B.A., and Yu, H. (2018). Last Place? The Intersection of Ethnicity, Gender, and Race in Biomedical Authorship. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108, 222–227.

-

-

O’Reilly, N. (2019). Why we’re creating Wikipedia profiles for BAME scientists. Nature d41586–019–00812–00818.

+

+Martin, G. (2015). Addressing the underrepresentation of women in mathematics conferences (arXiv).

-

-

Ruzycki, S.M., Fletcher, S., Earp, M., Bharwani, A., and Lithgow, K.C. (2019). Trends in the Proportion of Female Speakers at Medical Conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Network Open 2, e192103.

+

+Martin, J.L. (2014). Ten Simple Rules to Achieve Conference Speaker Gender Balance. PLoS Computational Biology 10, e1003903.

-

-

Sahai, H., and Khurshid, A. (1996). Statistics in epidemiology: methods, techniques, and applications (Boca Raton: CRC Press).

+

+Murray, D., Siler, K., Larivière, V., Chan, W.M., Collings, A.M., Raymond, J., and Sugimoto, C.R. (2019). Author-Reviewer Homophily in Peer Review. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

-

-

Santamaría, L., and Mihaljević, H. (2018). Comparison and benchmark of name-to-gender inference services. PeerJ Computer Science 4, e156.

+

+O’Reilly, N. (2019). Why we’re creating Wikipedia profiles for BAME scientists. Nature d41586-019-00812-8.

-

-

Shen, Y.A., Webster, J.M., Shoda, Y., and Fine, I. (2018). Persistent Underrepresentation of Women’s Science in High Profile Journals. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

+

+Ruzycki, S.M., Fletcher, S., Earp, M., Bharwani, A., and Lithgow, K.C. (2019). Trends in the Proportion of Female Speakers at Medical Conferences in the United States and in Canada, 2007 to 2017. JAMA Network Open 2, e192103.

-

-

Sood, G., and Laohaprapanon, S. (2018). Predicting Race and Ethnicity From the Sequence of Characters in a Name (arXiv).

+

+Sahai, H., and Khurshid, A. (1996). Statistics in epidemiology: methods, techniques, and applications (Boca Raton: CRC Press).

-

-

Wade, J., and Zaringhalam, M. (2018). Why we’re editing women scientists onto Wikipedia. Nature d41586–018–05947–05948.

+

+Santamaría, L., and Mihaljević, H. (2018). Comparison and benchmark of name-to-gender inference services. PeerJ Computer Science 4, e156.

-

-

Wais, K. (2016). Gender Prediction Methods Based on First Names with genderizeR. The R Journal 8, 17.

+

+Shen, Y.A., Webster, J.M., Shoda, Y., and Fine, I. (2018). Persistent Underrepresentation of Women’s Science in High Profile Journals. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

-

-

Witteman, H.O., Hendricks, M., Straus, S., and Tannenbaum, C. (2019). Are gender gaps due to evaluations of the applicant or the science? A natural experiment at a national funding agency. The Lancet 393, 531–540.

+

+Sood, G., and Laohaprapanon, S. (2018). Predicting Race and Ethnicity From the Sequence of Characters in a Name (arXiv).

-

-

Ye, J., Han, S., Hu, Y., Coskun, B., Liu, M., Qin, H., and Skiena, S. (2017). Nationality Classification Using Name Embeddings. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

+

+Wade, J., and Zaringhalam, M. (2018). Why we’re editing women scientists onto Wikipedia. Nature d41586-018-05947-8.

-

-

(2011). Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC).

+

+Wais, K. (2016). Gender Prediction Methods Based on First Names with genderizeR. The R Journal 8, 17.

-

-

(2015). Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC).

+

+Witteman, H.O., Hendricks, M., Straus, S., and Tannenbaum, C. (2019). Are gender gaps due to evaluations of the applicant or the science? A natural experiment at a national funding agency. The Lancet 393, 531–540.

-

-

(2016). Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer Science and Business Media LLC).

+

+Ye, J., Han, S., Hu, Y., Coskun, B., Liu, M., Qin, H., and Skiena, S. (2017). Nationality Classification Using Name Embeddings. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

@@ -1096,8 +1115,7 @@

References

}

/* table auto-number */

- table > caption > span:first-of-type,

- div.table_wrapper > table > caption > span:first-of-type {

+ table > caption > span:first-of-type {

font-weight: bold;

margin-right: 5px;

}

@@ -1324,6 +1342,15 @@

References

top: 0.125em;

}

+ /* -------------------------------------------------- */

+ /* references */

+ /* -------------------------------------------------- */

+

+ .csl-entry {

+ margin-top: 15px;

+ margin-bottom: 15px;

+ }

+

/* -------------------------------------------------- */

/* print control */

/* -------------------------------------------------- */

@@ -1455,7 +1482,6 @@

References

/* tablenos wrapper */

.tablenos {

- /* show scrollbar on tables if necessary to prevent overflow */

width: 100%;

margin: 20px 0;

}

@@ -1772,7 +1798,8 @@

References