Congratulations! You're here because you want to join the millions of open source developers contributing to mountebank. The good news is that contributing is an easy process. In fact, you can make a difference without writing a single line of code. I am grateful for all of the following contributions:

- Submitting an issue, either through github or the support page

- Commenting on existing issues

- Answering questions in the support forum

- Letting me know that you're using mountebank and how you're using it. It's surprisingly hard to find that out with open source projects, and provides healthy motivation. Feel free to email at brandon.byars@gmail.com

- Writing about mountebank (bonus points if you link to the home page)

- Creating a how-to video about mountebank

- Speaking about mountebank in conferences or meetups

- Telling your friends about mountebank

- Starring and forking the repo. Open source is a popularity contest, and the number of stars and forks matter.

- Convincing your company to let me announce that they're using mountebank, including letting me put their logo on a web page (I will never announce a company's usage of mountebank without their express permission or a pre-existing public writeup).

- Writing a client library that hides the REST API under a language-specific API

- Writing a build plugin for (maven, gradle, MSBuild, rake, gulp, etc)

- Writing a custom protocol implementation

Still want to write some code? Great! You may want to keep the source documentation handy, and you may want to review the issues.

I have two high level goals for community contributions. First, I'd like contributing to be as fun as possible. Secondly, I'd like contributions to follow the design vision of mountebank. Unfortunately, those two goals can conflict, especially when you're just getting started and don't understand the design vision or coding standards. I hope this document helps, and feel free to make a pull request to improve it! If you have any questions, I am more than happy to help at brandon.byars@gmail.com, and I am open to any all suggestions on how to make code contributions as rewarding an experience as possible.

The code in mountebank is now a few years old, and consistency of design vision is important to keeping the code maintainable. The following describe key principles:

I consider the REST API the public API from a semantic versioning standpoint, and I aspire never to have to release a breaking change of mountebank. In my opinion, the API is more important than the code behind it; we can fix the code, but we can't change the API once it's been documented. Therefore, expect more scrutiny for API changes, and don't be offended if I recommend some changes. I often agonize over the names in the API, and use tests to help me play with ideas.

Before API changes can be released, the documentation and contract page need to be updated. The contract page is, I hope, friendly for users, but a bit unfriendly for maintainers. I'd love help fixing that.

Most of mountebank is protocol-agnostic, and I consider central to its design. In general, every file outside of the protocol folders (http, tcp, etc) should not reference any of the request or response fields (like http bodies). Instead, they should accept generic object structures and deal with them appropriately. This includes all of the core logic in mountebank, including predicates, behaviors, and response resolution. To help myself maintain that mentality, I often write unit tests that use a different request or response structure than any of the existing protocols. This approach makes it easier to add protocols in the future and ensures that the logic will work for existing protocols.

Many development decisions implicitly frame a tradeoff between the developers of mountebank and the users. Whenever I recognize such a tradeoff, I always favor the users. Here are a few examples, maybe you can think of more, or inform me of ways to overcome these tradeoffs in a mutually agreeable manner:

- The build and CI infrastructure is quite complex and slow, but I'd prefer that over releasing flaky software

- I aim for fairly comprehensive error handling with useful error messages to help users out

- Windows support can be painful at times, but it is a core platform for mountebank

I do everything I can to resist code entropy, following the "no broken windows advice given by the Pragmatic Programmers. Like any old codebase mountebank has its share of warts. The following help to keep the code as clean as possible:

While all pull requests are welcome, the following make them easier to consume quickly:

- Smaller is better. If you have multiple changes to make, consider separate pull requests.

- Provide as much information as possible. Consider providing an example of how to use your change in the pull request comments

- Provide tests for your change. See below for the different types of testing in mountebank

- Provide documentation for your change.

The following steps will set up your development environment:

npm installnpm install -g grunt-cligrunt airplane

Note that running ./build (Linux/Mac) or build (Windows) will run everything for you even without

an npm install, and is what CI uses. The grunt airplane command is what I use before committing.

You can also run grunt, which more accurately models what happens in CI, but there are some tests

that may pass or fail depending on your ISP. These tests that require network connectivity and verify

the correct behavior under DNS failures. If your ISP is kind enough to hijack the NXDOMAIN DNS response

in an attempt to allow you to conveniently peruse their advertising page, those tests will fail.

When you're ready to commit, do the following

- Look at your diffs! Many times accidental whitespace changes get included, adding noise to what needs reviewing.

- Use a descriptive message explaining "why" instead of "what" if possible

- Include a link to the github issue in the commit message if appropriate

Try to avoid using the new and this keyword, unless a third-party dependency requires it. They

were traditionally poorly implemented in JavaScript, so I opted for a more functional code style.

In a similar vein, prefer avoiding typical JavaScript constructor functions and prototypes.

Instead prefer modules that return object literals. If you need a creation function, prefer the name

create, although I've certainly abused that with layers and layers of creations in places that I'm none

too proud about.

The code was written using ES4 and left that way for a long time to support node v4 and earlier. Now that node v4 is no longer supported, prefer using ES2015 features.

In the early days, the mb process started up quite quickly. Years later, that was no longer true,

but it was like boiling a frog, the small increase that came from various changes were imperceptible

at the time. The root cause was adding package dependencies - I had a pattern of making the require

calls at the top of each module. Since that was true for internal modules as well, the entire app,

including all dependencies, was loaded and parsed at startup, and each new dependency increased the

startup time.

The pattern now is, where possible, to scope the require calls inside the function that needs them.

In the spirit of being as lazy as possible towards maintaining code quality, I rely on linting heavily. You are welcome to fix any tech debt that you see in SaaS dashboards:

There are several linting tools run locally as well:

- eslint - I have a strict set of rules. Feel free to suggest changes if they interfere with your ability to get changes committed, but if not I'd prefer to keep the style consistent.

- custom code that looks for unused packages and

onlycalls left in the codebase

I almost never manually QA anything before releasing, so automated testing is essential to maintaining a quality product. There are four levels of testing in mountebank:

These live in the test directory, with a directory structure that mostly mimics the production

code being tested (except in scenarios where I've used multiple test files for one production file,

as is the case for predicates and behaviors). My general rule for unit tests is that they run

in-process. I have no moral objection to unit tests writing to the file system, but I aim to keep

each test small in scope. Your best bet is probably copying an existing test and modifying it.

Nearly all (maybe all) unit tests are protocol-agnostic, and I often use fake protocol requests

during the setup part of each test.

These live in the functionalTest directory, and are out-of-process tests that verify three types

of behavior:

- Protocol-specific API behavior, in the

functionalTest/apidirectory. Each of these tests expectsmbto be running and calls its API. - Command line behavior, in the

functionalTest/commandLinedirectory. Each of these tests spins up a new instance ofmband verifies certain behaviors - Website integrity, in the

functionalTest/htmldirectory. These expectmbto be running and validate that there are no broken links, that each page is proper HTML, that the feed works, that the site map is valid, and that the documentation examples are valid. That last point is unique enough that I consider it to be an entirely different type of test, described next.

The functionalTest/html/docsIntegrityTest.js file looks for special HTML

tags that indicate the code blocks within are meant to be executed and validated within the docs.

At first I wrote these tests as a check on my own laziness;

I know from experience how hard it is to keep the docs up-to-date. They proved quite useful,

however, as a kind of BDD style outside-in description of the behavior, motivating me to rewrite

the framework to make it easier to maintain. I'd like in the future to open source the docs tester

as a separate tool.

You start by writing the docs, with the examples, in the appropriate file in src/views/docs.

Wrap a series of steps in a testScenario tag with a name attribute to disambiguate it from

other scenarios on the same page (multiple test scenarios on the same page are run in parallel).

A step is a request/response pair, where the response is optional,

and is wrapped within a step tag. The request and response must be within a code element, and

are usually also wrapped in a pre block if they are meant to be visible on the page. To validate

the response, wrap the response code block within an assertResponse code block.

The simplest example is on the overview page, documenting the hypermedia on the root path of the API.

You can see the actual documentation on the website.

It makes a request to GET / and validates the response headers and JSON body:

<testScenario name='home'>

<step type='http'>

<pre><code>GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:<%= port %>

Accept: application/json</code></pre>

<assertResponse>

<pre><code>HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Vary: Accept

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 226

Date: <volatile>Sun, 05 Jan 2014 16:16:08 GMT</volatile>

Connection: keep-alive

{

"_links": {

"imposters": { "href": "http://localhost:<%= port %>/imposters" },

"config": { "href": "http://localhost:<%= port %>/config" },

"logs": { "href": "http://localhost:<%= port %>/logs" }

}

}</code></pre>

</assertResponse>

</step>

</testScenario>The actual response is string-compared to the expected response provided in the assertResponse code

block. To make the expected responses both easier to read from a documentation standpoint and

avoid problems of dynamic data, the following transformations are applied before the comparison:

- Any JSON listed is normalized, so you don't have to worry about whitespace within JSON

- You can wrap any data that differs from response to response in a

volatiletag, as shown with theDateheader above - If you want to display something other than what's tested, you can use the

changeelement - If you don't want to document the entire response to focus in on the key elements, you can set

the

partialattribute on theassertResponseelement totrue. The proxies page makes heavy use of this feature.

You can see an example using the change element on the getting started

page. The docs indicate that the default port is 2525, and so it intentionally displays all the

example requests with that port, even though it may use a different port during test execution:

<step type='exec'>

<pre><code>curl -X DELETE http://localhost:<change to='<%= port %>'>2525</change>/imposters/4545

curl -X DELETE http://localhost:<change to='<%= port %>'>2525</change>/imposters/5555</code></pre>

</step>The two examples just shown include two types of steps. The following are supported:

httpis the most common one, representing HTTP requests and responses.execis used for command line executions like the one shown abovesmtpis used for SMTP examples, as on the mock verification page. It expects aportattribute indicating the port of the imposter smtp servicefileis used to create and delete a file, as on the lookup examples on the behavior page. It expects afilenameattribute. If thedeleteattribute is set to "true", the file is deleted.

As the doc tests get unwieldy to work with at times, I will often comment out all files except the

one I'm troubleshooting in functionalTest/html/docsIntegrityTest.js.

I only have a few of these, to ensure a flat memory usage under normal circumstances and to ensure that the application startup time doesn't increase over time (as was happening as more package dependencies were added). Performance testing is a key use case of mountebank, so if you have experience writing performance tests and want to add some to mountebank, I'd be eternally grateful. These are run in a special CI job and not as part of the pre-commit script.

I was somewhat of a JavaScript newbie when I started mountebank, and even now, I don't actually code for a living so I find it hard to keep my skills up-to-date. If you're a pro, feel free to skip this section, but if you're like me, you may find the tips below helpful:

- mocha decorates test functions with an

onlyfunction, that allows you to isolate test runs to a single context or a single function. This works on bothdescribeblocks and onitfunctions. You'll notice that I use apromiseItfunction for my asynchronous tests, which just wraps theitfunction with promise resolution and error handling.promiseItalso accepts anonlyfunction, so you can dopromiseIt.only('test description', () => {/*...*/}); - Debugging asynchronous code is hard. I'm not too proud to use

console.log, and neither should you be. - The functional tests require a running instance of

mb. If you're struggling with a particular test, and you've isolated it using theonlyfunction, you may want to runmbwith the--loglevel debugswitch. The additional logging exposes a number of API and socket events.

A combination of only calls on tests with console.logs alongside a running instance of mb

is how I debug every test where it isn't immediately obvious why it's broken.

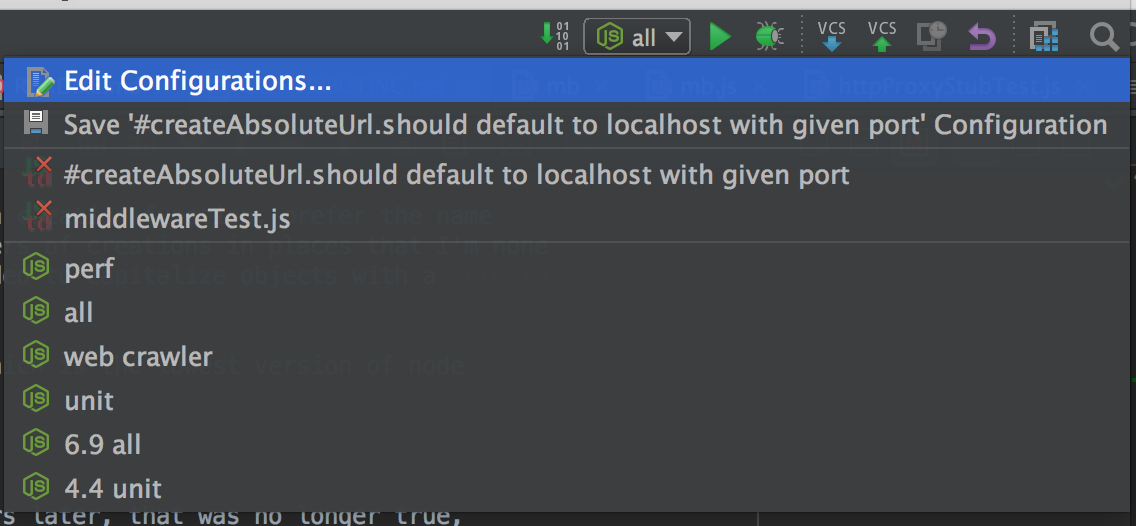

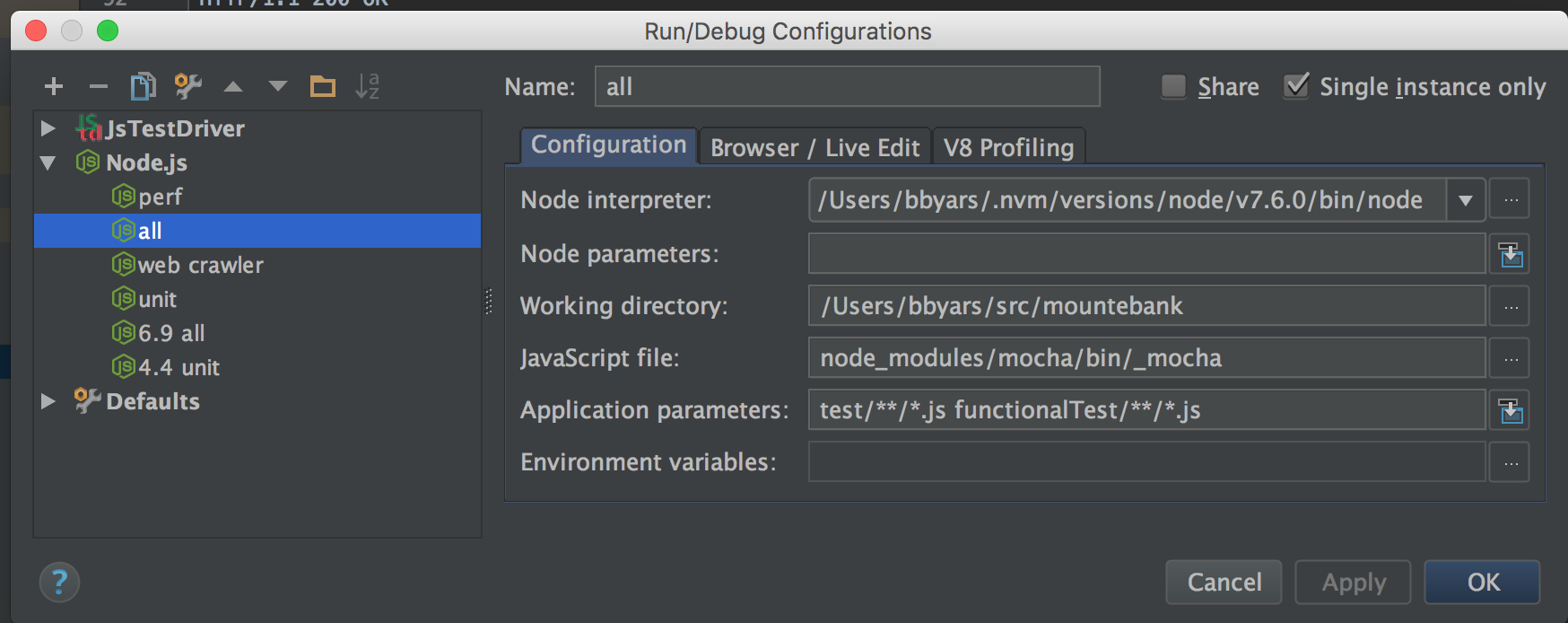

I use IntelliJ to develop. I've found it convenient to set up the ability to run tests through the IDE, and use several configurations to run different types of tests:

The screenshot below shows how I've set up the ability to run unit and functional tests as part of

what I've called the all configuration:

That configuration assumes mountebank is running in a separate process. I also have a configuration that removes the

functional tests from the 'Application Parameters' line, which runs the unit tests without any expectation of

mountebank running. Combined with the only function described in the Debugging section above, I'm able to

do a significant amount of troubleshooting without leaving the IDE.

I use nvm to install different versions of node to test against.

The pipeline is orchestrated in CircleCI, although it uses TravisCI and Appveyor for OSX and Windows tests. I've had bugs in different operating systems, in different versions of node, and in the packages available for download. The CI system tests as many of those combinations as I reasonably can.

Every successful build that isn't a pull request deploys to a test site that will have a link to the artifacts for that prerelease version.

Very few of you will have to worry about this, but in case you're curious, here's the process. CircleCI does most of the heavy lifting.

- Make sure the previous builds pass across all operating systems, install types, and node versions

- Review major / minor version.

- Update the releases.json with the latest release

- Add

views/releases/vx.x.xwith the release notes. Make sure to use absolute URLs so they work in aggregators, etc - Make sure all contributors have been added to

package.json - commit

- push

- wait for the build to pass

git tag -a vXX.YY.ZZ -m 'vXX.YY.ZZ release'git push --tags- update version in package.json to avoid accidental version overwrite for next version

The source documentation is always available at Firebase.

I'm also available for questions. Feel free to reach me at brandon.byars@gmail.com