| title | author | publish_on | type | canonical_url | image | excerpt | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Plant physiologists used high throughput computing to remedy research “bottleneck” |

Sarah Matysiak |

|

user |

|

The Spalding Lab uses high throughput computing to study plant physiology. |

HTC resources increased the efficiency of the Spalding group's data analyses, which enabled an increase in the scope of their research.

Enhancing his research with high throughput computing was a pivotal moment for University of Wisconsin–Madison molecular plant physiologist Edgar Spalding when his research group adopted it in 2006. Over the past five years, the research group has used more than 200,000 computing hours, including to facilitate "the development of the measurement algorithm and the automatic processing of tens-of-thousands of images" of maize seedling root growth, Spalding says.

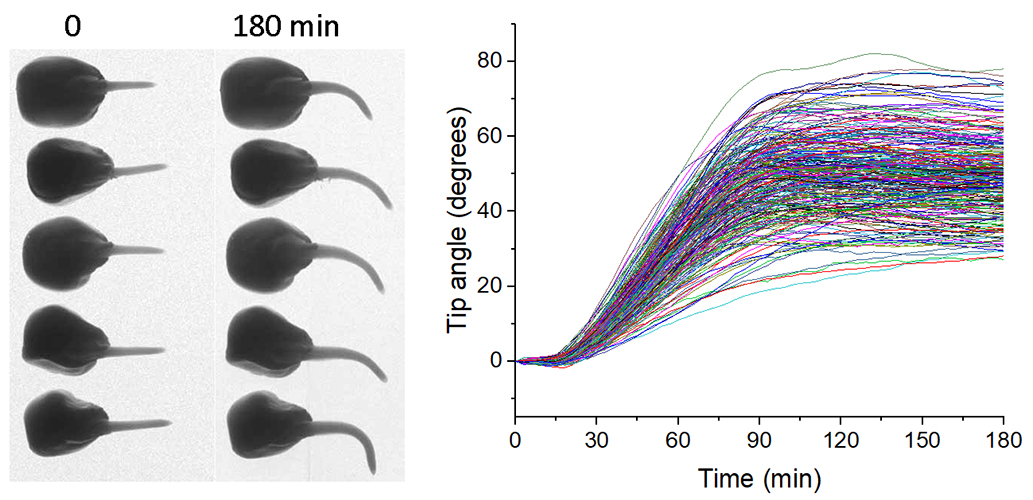

The graph shows the average gravitropic response of each of the maize types. Statistical genetics techniques mapped variation in these curves (the phenotype) to genes that control the process. HTCondor scheduling software and computing resources at CHTC were used to develop the measurement algorithm and to process the tens of thousands of images automatically.Spalding’s research group was studying Arabidopsis plant populations with genetically diverse members and tracking their response to light or gravity due to a mutation — one seedling at a time. Since Arabidopsis seedlings are only a few millimeters tall, Spalding says his research group found that obtaining high-resolution digital images was the best approach to measure the direction of their growth. A computer collected images every few minutes as the seedlings grew. “If we could characterize this whole genetically diverse population, we could use the powerful techniques of statistical genetics to track down the genes affecting the process. That meant we now had thousands and thousands of images to measure,” Spalding explains.

The thousands of digital images to measure created a bottleneck in Spalding’s research. That was before he led an effort with the Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC) Director Miron Livny, other plant biologists, and computer scientists to develop a proposal for a competitive National Science Foundation (NSF) grant that would produce cyberinfrastructure to support plant biology research. Though the application wasn’t successful, the connections Spalding made from that meeting were meaningful nonetheless.

Speaking with Livny at the meeting — from whom he learned about the capabilities of the HTC approach that was pioneered on our campus — helped Spalding realize the inefficiencies of his group in analyzing thousands of seedlings. “[O]ur research up until that point had been focused on one seedling at a time. Faced with large numbers of seedlings to do a broader scale of investigation meant that we had to find computing methodologies that matched our new data type, which was tens of thousands of images instead of a couple of dozen. That drove our need for a different way of computing,” Spalding describes.

When asked about which accomplishment using HTC was most impactful, Spalding said “The way we measure yield-related features from maize ears and several thousand kernels has had a large impact.” Others from around the world began asking for their help with making similar measurements. “In many cases, we can use our workflow [algorithms] running on CHTC to process their images of maize ears and kernels and return data that helps them answer their scientific or crop breeding questions,” Spalding says.

Since the goals of the experiments determine the type of data the researchers collect, they did not need to adjust the type of data they collected. Rather, adopting the HTC approach changed the way they created tools to analyze the data. Today, Spalding says his research group continues to use HTC in three ways: “from tool development to extracting the features from the images with the tool that you developed to applying it in the challenge of statistically matching it to elements of the results to elements of the genome.” As his team became more experienced in writing new algorithms to make measurements, they realized that HTC was useful in developing new methodologies; it was more than just more automation and increased computing capacity.

In other words, HTC is useful as both a development resource and a production resource. Making measurements on seedlings and then matching processes to the genome elements that control those processes involved an ever-growing amount of computing capacity. “We realized that statistical modeling of the measurements from the biology to the genetic information in the population also benefited from high throughput computing.” HTC in all these cases, Spalding elaborates, “was beneficial and changed the way we work. It changed the nature of the questions we asked.” In addition to these uses of HTC, the research group’s uses of machine learning (ML) also continue to become a bigger part of the tool development stage and in driving the methods to train a model to recognize a feature in a seedling.

Spalding has also shared his HTC experience with the attendees of the annual OSG School. Spalding emphasizes that students “should not hold back on doing something because they think computing will be a bottleneck. There are ways to bring the computing they need to their problem and they should not shy away from a question just because they think it might be difficult to compute. There are people like the CHTC staff that can remove that bottleneck if the person’s willing to learn about it.”

“Engaged and motivated collaborators like Spalding and his group is what guides CHTC in advancing the state of the art of HTC and drives our commitment to bring these advances to researchers on the UW-Madison campus and around the world,” says Livny.