This guide is part of MI-AFP course of functional programming but brings and summarizes broader ideas what to consider when developing an open-source project, i.e., not necessarily in Haskell or Elm. We try to cover all important aspects and use references to existing posts and guides with more complete descriptions and explanations. If you find anything wrong or missing, feel free to contribute in open-source matter 😉

When you have ideas or some assignment what to program, you can easily create project and start coding right away. That might go well for some smaller project but sometimes even for tiny utility script you might end up shortly in "no idea" zone. Usually, it is better if you think first about what you want to accomplish, how it can be done, and then setup some productive enviroment for work itself.

At first, do a mindmap (it is really helpful tool for creativity) or a list of things that your project should do in terms of functionality and its behaviour and look. In software engineering, there are functional and non-functional requirements. Functional are trivital, just list what the app should do, e.g., communicate with GitHub API to list labels of given repository.

On the other hand, non-functional requirements might be more complicated to summarize. They cover many areas and some can be, for instance, it will be in form of web application, it will use relational database, it will have internationalization, and so on. In general, for requirements, you should think about FURPS:

- Functionality - Capability (Size & Generality of Feature Set), Reusability (Compatibility, Interoperability, Portability), Security (Safety & Exploitability)

- Usability (UX) - Human Factors, Aesthetics, Consistency, Documentation, Responsiveness

- Reliability - Availability (Failure Frequency (Robustness/Durability/Resilience), Failure Extent & Time-Length (Recoverability/Survivability)), Predictability (Stability), Accuracy (Frequency/Severity of Error)

- Performance - Speed, Efficiency, Resource Consumption (power, ram, cache, etc.), Throughput, Capacity, Scalability

- Supportability (Serviceability, Maintainability, Sustainability, Repair Speed) - Testability, Flexibility (Modifiability, Configurability, Adaptability, Extensibility, Modularity), Installability, Localizability

Also, you need to consider your own expectations:

- What do you want to learn

- Are you going to work in team or alone

- Do you want to publish it or is it just private work

- etc.

Hmm, you have requirements... so you can start to work. Well you can, but maybe it is good idea to now take your list of requirements and do a bit of reasearch what solutions already exist. Not only that you might find out that you would totally "reivent the wheel" and the software you want to develop is already here and you would just waste your precious time, but you might get inspired and learn from other's mistakes.

- Find (for example using Google) similar existing solutions if there are any

- Take a look at each and write down what your like and dislike and how much it fulfils your requirements

- If some fulfils its completely and you like it, you don't need this project probably

- Adjust your requirements based on research and/or make summary list what to avoid in your app (what you didn't like in the existing solutions)

Before you start, you need to consider what you will use. What programming language(s) are you going to code in, what framework will you use and what external libraries. That will also highly affect tools, the architecture, and overall structure of your project. These technologies are filtered mostly by:

- non-functional requirements (such as type of application, speed, accessibility, etc.),

- what are you able to work in (or able/keen to learn it),

- what are you allowed to used (licenses or internall restrictions).

If there are still more options remaining, do the research how is the specific technology widespread and how it suits your task. A bigger and more active community around the technology means better for your project since there will be people to answer your questions eventually. Important last word about this, sometimes it is healthy to get our of your comfort zone and try something new that you are not totally familiar with, spend time to learn and try it (if you can)...

Finally you know what are you going to code and what technologies will be used. That is sufficient to easily setup the environment for you to code efficiently:

- IDE - the central point where you will work, there are again many options based on the technologies you want to use - IntelliJ IDEA, VS Code, Visual Studio, PyCharm, KDevelop, NetBeans, Eclipse, etc.

- Plugins for technologies - IDE usually can be enhanced with plugins specialized for your programming language(s) and framework(s), usually it consists of syntax highliting, linter, auto completion, preconfigured action, or code snippets

- VCS (see below) - ideally integrated within IDE

- Build & test automatization - it is nice to be able to build, run, or test the application without leaving IDE and ideally with single action

Don't forget, that this is highly subjective and depends really on you what you prefer. Some people are really happy with Vim and its plugins. Some prefer other simpler editors with UI similar to Notepad++. But most of programmers like full-fledged IDE providing all what they need easily.

Important part of a productive environment (and not just for team, even if you are the only developer) is something called Version Control System. As the name is well-descriptive, it allows you to keep track of changes of your work and in the most tools not just in single line but in branches that can be merged afterwards. It allows you also to go back when needed, check who made what changes and when, tag some specific revisions and many more.

The most famous version control systems these days are Git and SVN (subversion). Frequently, you can stick with rule that SVN is more suitable for larger and binary files (although there is Git LFS) or when good integration for specific tool is supplied (for example, Enterprise Architect). The core difference is in approach that SVN is centralized and you need to lock part that you want to change, this is where Git will require you resolve merge conflicts. Merging and branches in SVN are more complicated than in Git (this many be subjective).

For more see: https://www.perforce.com/blog/vcs/git-vs-svn-what-difference

Of course, you can use Git only locally or deploy your own basic Git server to have backups and you will have your work versioned and backuped. But to gain the most of it, using public web-based hosting services for Git is essential. There are more but for the widely used, we can enumerate: GitHub, GitLab, and BitBucket. The main advantage is in public sharing of open-source project for free and easily opening them to contributions.

Aside from the basic Git functionality, related features to support the software development process are supplied. One of the key features are issues for reporting bugs, sharing ideas, and discussing related stuff. Others are Pull Requests (or Merge Requests) with reviews that allow to control contributions from externals into the project as well as merge of internal branches of multiple developers. Moreover, many functions for project management (e.g., kanban boards, labels, assignments, and time tracking) and documentation (wiki pages, web-based editors, documentation sites integrations, etc.) are available.

Another important advantage is that there are more services that can be integrated with these hostings such as CI, code analytics, deployment environments, project management systems, etc. As a disadvantage one can see providing own work publically or to some company. For that, there are private repositories (sometimes paid) or you can create own deployment of GitLab on your server or for organisation and then share the work publically but under full control.

Git allows you to develop in branches and make units of change called commits. A very good practice is to setup guidelines for you, your team, and/or external contributors how to split work into branches and how to compose commit messages. There is so-called Gitflow Workflow that describes naming and branching of code in universal and nice way. Relating branches and Pull Requests to certain issues seems to be useful for tracking.

Important also is to have atomic commits so one commit is only one change of your code. That helps you when going through the changes in time and cherrypicking some of them or alternating them. A good description of commit is vital as well. There is always a short message but then you can include a more elaborate description if needed. But it should be always clear from the message what the commit changed in the project and even when you don't know the previous or following messages. Messages such as "Bugfix app", "Web improvement", "Another enhancement", "Trying again", are really bad!

Imagine your have a great piece of software that can help a lot of people, it is somewhere but noone knows what it is and how to use it. To help with that, you need to provide a documentation. Of course, you should always use "standard" way of installation for given programming language and platform as well as follow conventions how to use the app, but even dummy user should be able to get the information somewhere.

Your documentation should always cover:

- What is your project about

- How to install and use the application (as easy as possible)

- Configuration details and more options ("advanced stuff")

- API (if library or service)

- How to contribute (if opensource)

For documentation, you can write your own, you can try to fit in single README file (for smaller projects) or use some service such as GitHub Pages, ReadTheDocs, or GitBook (there are many more). There are more views on your project - user, administrator (for example in case of web application), and developer. You should provide documentation for all of them with some expectations about their knowledge and experience. For developers, standard documentation directly in the code can be very useful.

Quality of your code (as well as other parts of your project including documentation, communication, and quality assurance itself) is important for others and you too. Maintaining code that is well-writen using standard consistent conventions, is properly tested (i.e. works as it should), and is easy to read and handle, is a way easier. You should invest the time to assure quality of your project and it will definitely pay back.

When talking about quality of code, the first that comes to mind of most people is testing. Of course, you should properly test your software with unit and integration tests. For the selected programming language(s) and framework(s) there should be some existing testing frameworks and guidelines how to write tests, how to make mocks, spies, and other tricks in testing. Often, people measure "coverage" which percentage of statements covered by your tests. It can be useful to check whether changes in your code increase or decrease the coverage.

But be careful, 100 % coverage does not mean that your code is working correctly. You can get such coverage easily with stupid tests that will be passed even by totally bugged implementation. When writing tests you should follow:

- All main parts/units are tested (separately, unit tests)

- Communication between units is tested (integration tests)

- There are also "negative" tests, not only positive - i.e. don't test only that things work when they should work but also that they don't work if the shouldn't

- If external services (for example some REST API) is used, never test with live version - use mocks or records of the communication

Interesting testing approach that is lately often used since more and more web applications are being developed is called end-to-end tests. It tests whole application as user would use it. In case of CLI, it tries to use the app using the CLI and checks the outputs. In case of web application, it uses real (or "headless") browser and clicks or fills some forms in it and again checks how the page behaves. It takes some time to setup such tests and start writing the cases, but again - it pays off in bigger projects since usually the tests are well-reusable.

By code quality we mean things covered by static code analysis. Tests use your app running (i.e. dynamic) but static analysis just checks the programming code without any execution. There are many tools for that and they mainly cover:

- Conformity with conventions and rules for writing code (naming variables, indentation, structuration of files, ...)

- Repetitions in code (i.e. violations against DRY principle)

- Using vulnarable code and libraries or deprecated constructs

- Not handling exceptions correctly

- Incorrect working with types

- etc.

Moreover, some tools can be integrated with GitHub or GitLab and check all your pushed commits easily.

Programming alone has a few serious risks especially when you get lazy:

- skipping the documentation or making it useless

- writing code in a way that only you (at least you should!) understand it

- incorporate nasty bugs

- making dummy tests or none at all

To avoid that, you need some people to do reviews for you and do the review for others (for example, contributors to your project or team members). Moreover, pair programming is also a good practice of extreme programming. Try to be in positive mood both when writing review and being reviewed, in both cases you can learn a lot from others who has different experience in software development.

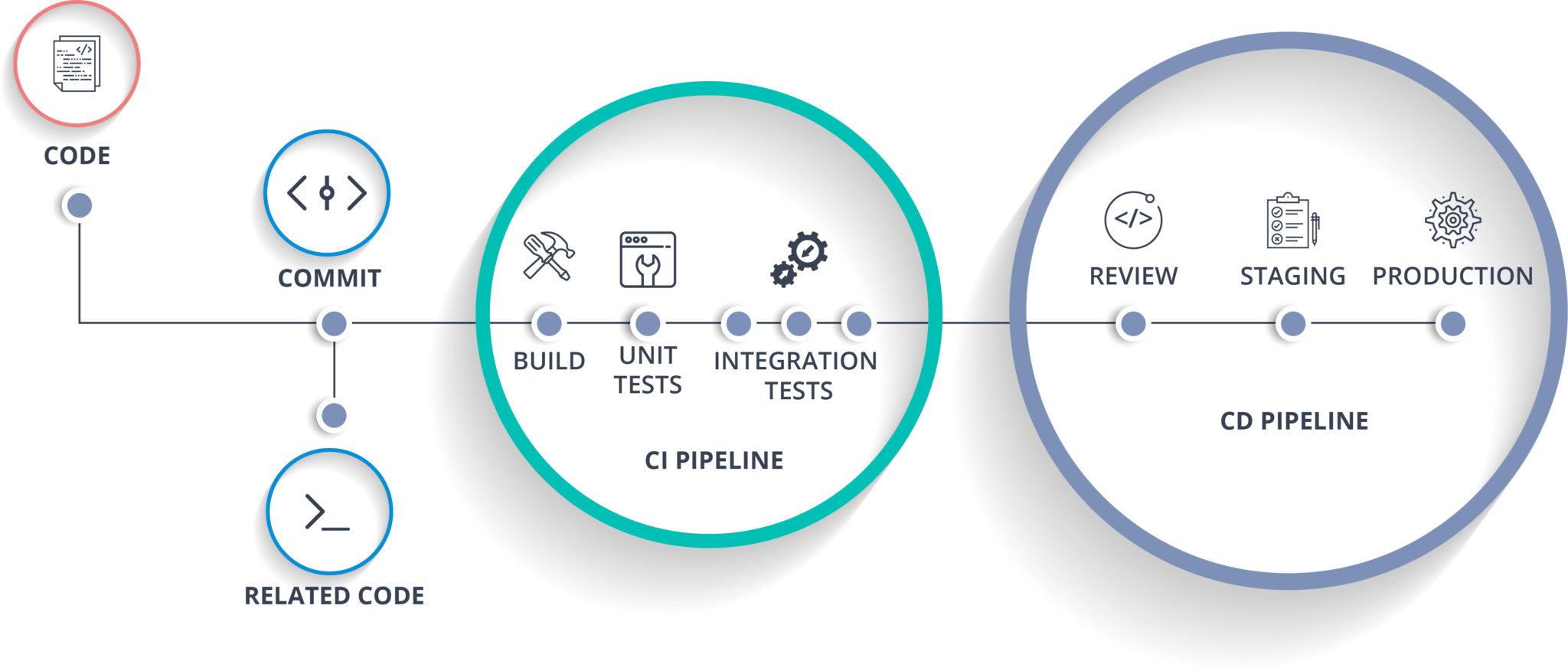

As already being said few times, there are services that can be easily integrated with GitHub or GitLab in order to do something with your project automatically when you push commits, create pull request, release new version, or do some other action. The "something" can be actually anything and you can write such "CI tool" even by yourself.

- Continuous Integration - This term is used usually when your software is built (all parts are integrated), and tested with automatic tests or at least attempt to execute it is done. The result is that at that moment your code is (at least somehow) working. It is nice to see in your commits history which were working and which were not. For this, you can use Travis CI, Semaphore CI, AppVeyor, and many others.

- Continuous Inspection - Services that does static inspection of your code, they can verify dependencies of your project, evaluate coverage, and others. One of the examples is SonarQube, but again there are many similar services.

- Continuous Delivery - If your code passed the build and test phases, it can be deployed somewhere. The deployment can have many realizations, from actual deployment on some web hosting or app server (realized, for example, by service like Heroku or AWS), though publishing new documentation on ReadTheDocs, to uploading installation packages to some registry. All depends what you need, want, and how you will set it up.

When you want to publish something, in our case usually programming code, you are required to state under what terms is your work published, can be used, edited, or distributed. There are many licenses for open-source and you should not write your own, try to find existing and suitable first. Very good site that can help you is choosealicense.com. More complete one is located at opensource.org/licenses.

Also, if you create some graphics, you should consider Creative Commons license that is usually well-suitable for things like diagrams, images, textures, or posters. When your project is build from separated modules, those modules can be even licensed under different terms. For example, your library can be published under MIT and GUI app wrapping the library under GPL. Sometimes such licensing might be good, but having small app divided and licensed with many different licenses might cause headache to anyone who would like to use it.

On the other hand, as you usually use libraries and other projects made by different people than you are (or even yours!), you need to take into account the licenses of such included and used software, graphics, and anything. If someone states that you cannot use their work in conditions you are using, then you need to find another solution. Problems are also with so-called "Share-Alike", i.e., you need to license your code under the same license (for instance, GPL works like that). That limits your options when picking a correct license...

If you develop open-source project, you need to open for contributions of other people. Sometimes this requires a time to review new code, teach people, and have a lot of patience with them. You can take advantage of it, and if you want, ask active contributors to help you with the project maintaining. That is how world of open-source works and as everything it has advantages and disadvantages. It is always up to you, what do you want to do with your own project... Good luck!