(credit Peter Dragos)

This document expands on the transaction token pattern and the transaction token protocol architecture. Both the pattern and the architecture were concieved with the ultimate goal of providing a practical grounding for the theory introduced in this document.

We present a loose mathematical formalization of the subject at hand, followed by a worked example. The first section assumes some knowledge of category theory, while the examples provided should be intuitive regardless. Readers unfamiliar with category theory are encouraged to skim the first section and jump to the second, referring back to the first as they grow more comfortable with the primary goal of applying the theory.

The goal of this sketch is to lay out the framework for thinking of protocols as categories. This provides a formalization that may prove useful to formal verification, provide insight into the design and implementation of Cardano dApps, and provide inspiration from development frameworks for smart contracts that reify the abstractions presented within.

However, the key initial goal of this sketch is to translate protocols into a symmetric monoidal categories, or SMCs. SMCs have a pleasant representation as wiring diagrams, which make use of a graphical iconography amenable to equational reasoning, modularity, and composition. The laws required by SMCs are exactly those that are necessary to make such an iconography formal, and is the justification for approaching protocol design in this manner.

Protocols Partitioned into Strict Transaction Families form Categories that can be Presented via Wiring Diagrams

If we constrain ourselves to a strict partitioning of a protocol, the protocol seems to become a Symmetric Monoidal Category (or SMC). This allows a formal graphical presentation via wiring diagrams. If you are completely unfamiliar with wiring diagrams, we refer you to chapter 2 of Seven Sketches __ (chapter one may be useful for background, but is not strictly necessary to gain an intuition if one is comfortable with basic set theory, algebra, and order theory.)

N.B.: different types of diagrams have different mathematical properties. "Wiring diagrams" (proper) are suitable for SMCs, but an alternate formalization may be more sutiable. See additional materials for links to papers and videos on what might prove useful. In particular, this paper on the operad of temporal wiring diagrams seems promising; in allows for the notion of "types" and temporality.

This category has the following constituents:

- Objects are indexed sets formed from a generating set

G_cof "component addresses". This set corresponds exactly to the validators and minting policies introduced by the protocol. While not strictly necessary for the formalization to make sense, we can think of Minting Policies in the following way:- Minting Policies are thought of as locking an infinite number of UTxOs, each with an arbitrary number of tokens of their currency symbol.

- Minting is thought of as consuming one of those UTxOs at the minting policy address.

- Burning is thought of as paying those tokens to an "Always fail" validator.

- We add to

G_ca setW_cthat represents any address that is a validator or minting policy not introduced by the protocol.W_ccontains "everything else" that we may need a semantic understanding of: user wallets, third-party validators or minting policies involved in our transaction families, and so forth. (N.B.: We chooseW_cfor "wallet components", since most protocols will need to define a component representing pubkey addresses). - Morphisms are formed from a generating set,

G_tf, that is in bijection with the transaction families of the protocol. A morphism exists between two objects if there exists a valid transaction between the source and the target. - The identity morphism can be interpreted as "no valid transaction was submitted involving these objects".

- The monoidal product is the disjoint union of objects. I.e., "x⊗y" constitutes an object that can be consumed by a morphism consuming UTxOs at validators x and y.

- The monoidal identity I is the empty indexed set. It is represented in the wiring diagram by the absence of a wire.

- The monoidal product forms parallel transactions with morphisms. I.e., "f⊗g" means that transactions f and g are executed in the same block. The monoidal product of morphisms does not assume a proof that such a scenario exists in practice, only that such a scenario is possible.

N.B.: the definition of the category above omits details about what is meant by "indexed set" and "disjoint union" for the definition of objects and monoidal product, respectively. There is a common construction in category theory to formalize these, but the details are not necessary to built intuition and have thus been left out.

The simplest intuition is as follows. Objects are essentially a mathematical object sufficient to give an uncurried type signature, such as saying that

ftake a tuple of objects of a particular type and produces a tuple of objects of a particular type. The monoidal product can then be interpreted as "if we have two functionsfandg, to run both we need objects of the types from the domain of both."

A "zero morphism" is any morphism that takes the form zero_x : I → x. The monoidal unit is represented in wiring diagrams as the absence of a wire, so a zero morphism has the appearance of "x coming from nothing".

Objects with zero morphisms establish one boundary of the protocol. It captures the notion that in Cardano we cannot prevent a UTxO from "appearing out of thin air" since validation logic only applies to spending a UTxO and not creating one.

Category theory tends to view objects from the perspective of the morphisms between them. From this perspective, certain objects do have a notion of being "non-zero". The example is an object tied to a state token that requires certain initial conditions to be met for the state token to be minted; if properly implemented, these UTxOs cannot just "pop into existence" in a manner that permits them to participate in any transaction. We can always track their existence back to state token initialization policy, and a combination of such a policy along with well-written validators can greatly narrow the scope of UTxOs that will validate.

We also have a notion of a morphism discard_x : x → I. We do not say that every object has a discard morphism, but for those that do we make the following claim:

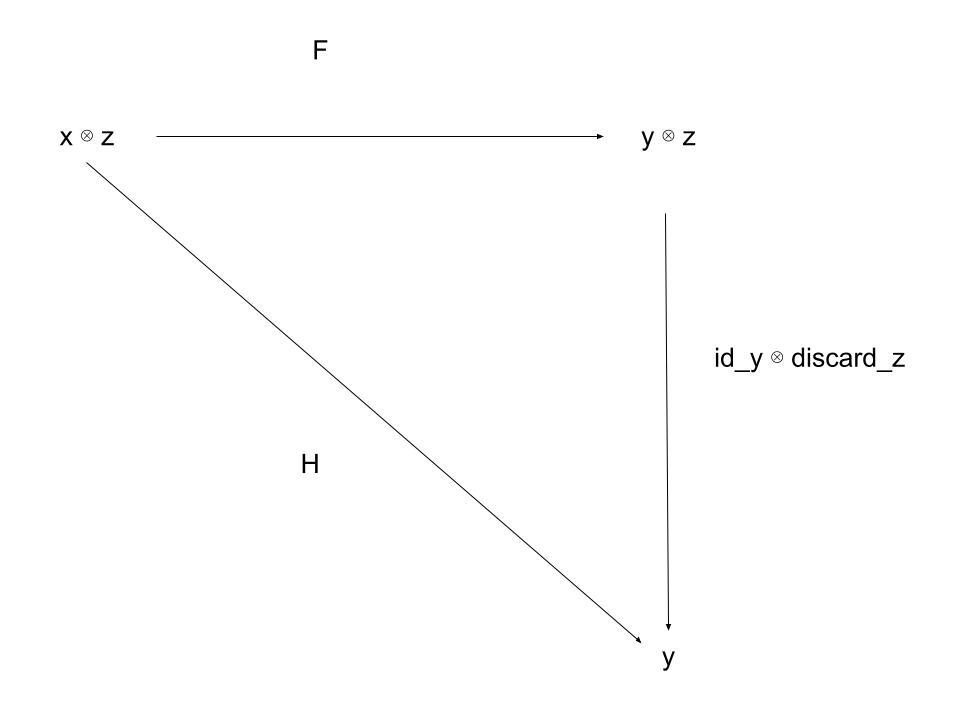

- For every morphism discard_z and morphism F : x ⊗ z → y ⊗ z, there exists a morphism H such that the following diagram commutes:

This establishes the intuition that certain objects can "cease to exist" from the view-point of the protocol, and the discarding of such objects after a transaction is indistinguishable from the discarding within the transaction. This is especially important when considering balancing a transaction: leftover funds may or may not exist, but requiring a separate transaction family for either case is more burdensome than considering such funds to have "disappeared".

In certain cases, it is useful to note whether a given object is discardable. For instance, UTxOs that are tied to state tokens may only be discardable under certain conditions, and must be represented as continuing UTxOs otherwise.

If we wish to think of component addresses as the objects of a symmetric monoidal category, we have to think of the monoidal product of component addresses as objects, too. This is fairly straight forward.

Suppose we have an object x = {V1, V1, V2} and an object y = {V2, V3} (where the brackets denote indexed sets rather than sets). Then we also have an object called x⊗y = {V1, V1, V2, V2, V3}. But since monoidal products are given as functors C x C → C, if we have morphisms f : x → a, g : y → b, we also need the morphism f ⊗ g : x ⊗ y → a ⊗ b.

Since f ⊗ g is a morphism, it is built up from Transaction Family from our morphism generating set G_tf. In terms of the correspondence of the protocol category to the actual on-chain representation of transactions, this would be interpreted as a multiple transactions running in parallel. That is, if f and g are members of G_tf (i.e. transaction families proper), then f ⊗ g represents a situation where both a transaction in the family f and a transaction in the family g were validated in the same block.

In addition, the composition of morphisms is also a morphism. That is, if f : a → b and g : b → c are morphisms, then there exists a morphism h : a → c such that h = f ; g. This is interpreted as the outputs of one transaction being fed unmodified as the inputs to another.

At this level, Transaction Flows are equivalence classes of morphisms, with the equivalence again being semantic. This will become more apparent below.

Since our monoidal product is symmetric, it is important to make some additional clarifications. Again using our example above, we have (by the symmetry law) that:

x⊗y = {V1, V1, V2, V2, V3} = y⊗x = {V2, V3, V1, V1, V2}

and

f ⊗ g : x ⊗ y → a ⊗ b == g ⊗ f : y ⊗ x → b ⊗ a

From the perspective of reification into the architecture, this means that, when passed a txInfoInputs scriptContext :: [TxInInfo], we may need some additional logic to give the semantic meaning of "which inputs go where". Such logic can be captured, for instance, by passing in a mapping as a datum to the transaction that maps the [TxInInfo]of the txInfoInputs field of the ScriptContext to the correct ordering as needed by the TxTMP. The key point for readers to be aware of is this: although our monoidal product is symmetric, there is nothing preventing us from choosing a canonical ordering of inputs and outputs provided that we retain a mechanism to permit reordering when we need it.

This is the "wiring" part of the wiring diagrams that will be shown below; the "reordering" of inputs and outputs becomes identified with the crossing of wires.

In this section, we'll build up our first wiring diagrams. Some of the formalisms we presented above are still loose, but readers should gain an intuition as to why they are usefuland what a full formalization would look like regardless.

We take the LiqwidX Action Queue model as an example with 3 supply and 3 demand queue lanes. We'll first work through the wiring diagrams of the basic action queue that only permits borrowing actions, and then we'll see how we can add batched collateral seizure while re-using some components and augmenting others.

N.B.: This repo is private. If anyone without access makes it this far and wants a more detailed rundown of the protocol in question, reach out to Peter Dragos . LiqwidX is a more featured version of the protocol described in "Transaction Token Pattern".

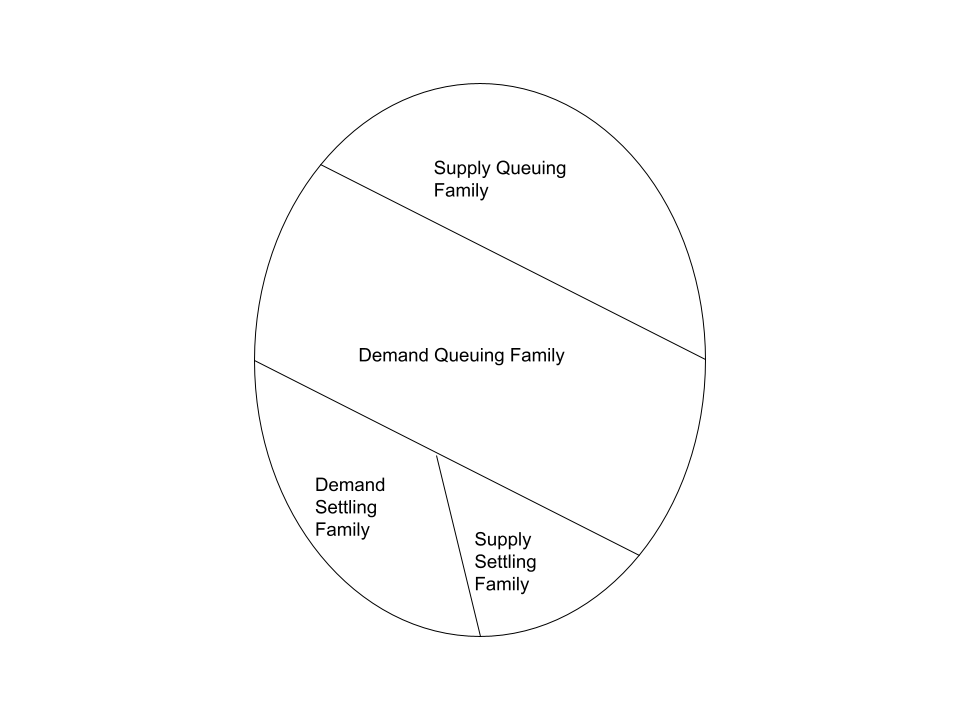

The basic idea is to separate possible actions into "supply" actions which make the system less constrained (such as adding collateral or repaying debts; these actions always succeed) and "demand" actions which make the system more constrained (such as removing collateral or originating more debt; these actions may not succeed if they push the system too far "into the red".)

Supply and demand actions are first "queued" by consuming one of a fixed number of "Queue UTxOs" via a "Queuing Family Transaction", which registers the intent to interact with the system in the Datum of the output Queue UTxOs. The number of Queue UTxOs that the system can handle is referred to as the number of "Queue Lanes". There are separate lanes for Supply and Demand queues.

Once a number of actions are queued, they are consumed by a "Settling Family Transaction". Transactions in this family consume the Queue Lanes and the Vault Manager (which tracks global debt and collateral balances), and apply any updates to the Vault Manager. The output produces fresh Queue UTxOs, an updated Vault Manager UTxO, and in the case of the Demand Queue only, executes permissible transfers from Vaults to User Wallets.

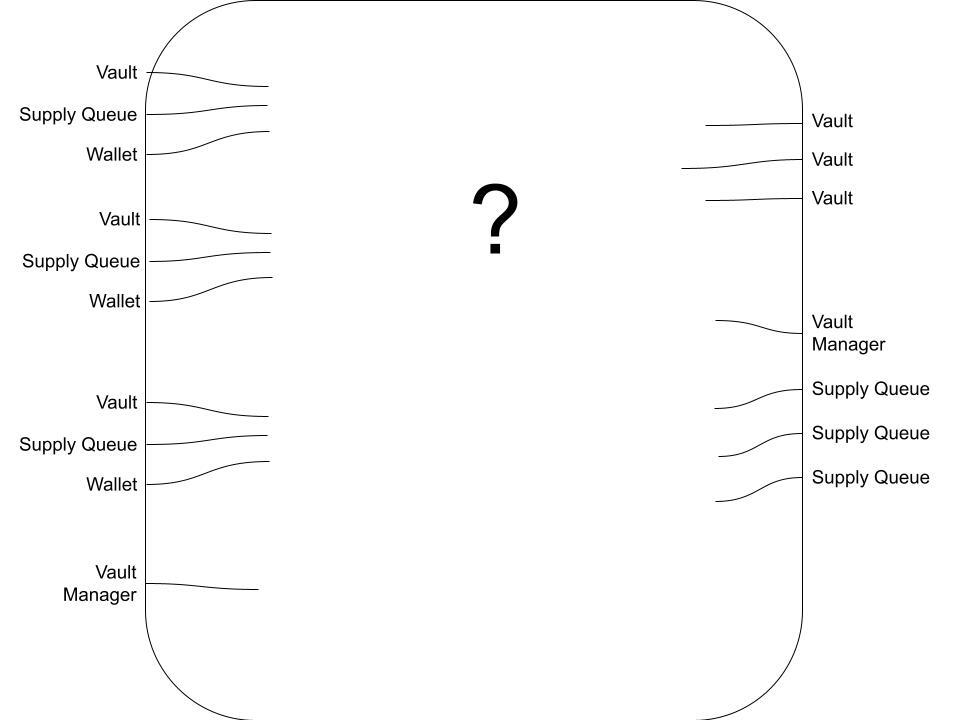

As described, our partitioning looks something like this (ignoring bootstrapping transactions, for now):

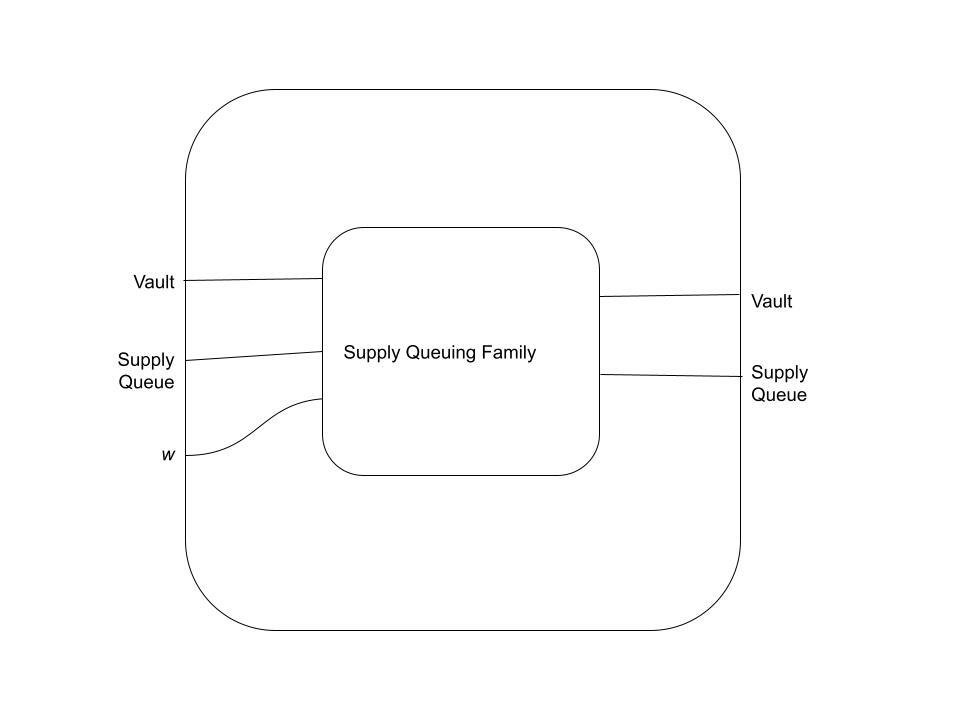

With the proposed setup, we can present a transaction family as a box with lines going into and out of it. The lines on either side of outer box represent components from our generating set G_c. Parallel horizontal lines represent the monoidal product of objects.

The outer box represents the boundaries of the system (in a way that will become more apparent shortly). The inner box represents a morphism that is either a transsaction family (a morphism from the set G_tf) or is built up from multiple transaction families using composition or the monoidal product.

Our first example is the Supply Queuing Family. This family contains transactions that take a Vault UTxO, a Supply Queue UTxO, and a w UTxO, and produce Vault and Supply Queue UTxOs. Here, w is a polymorphic component that is not introduced by our protocol that can be a priori consumed in a Supply Queueing transaction; we are essentially saying "we need to add funds to the system as part of this transaction, but we don't really care where they come from as long as we can unlock them".

Semantically, the operation being represented is as follows:

- Funds are taken from

wand added to the Vault, either increasing the collateral balance or repaying debt. Any leftover funds fromware paid back tow. We don't care aboutwafter this (there's nothing our protocol enforces about the leftover funds), so we don't representwon the right hand side of the diagram; we've discardedw. - An "empty" supply queue UTxO is consumed as input, and the supply queue UTxO is "filled" at the output. This registers an action that is suitable to be batch-processed into the Vault Manager to update global state.

- Note that we don't have any a priori notion that the supply queue will be empty. We can either establish such a notion at the "type" level by distinguishing between empty and full supply queues, or we can simply enforce it as part of the TxTMP of this transaction family.

Our wiring diagram is below. It represents a morphism from the set G_tf from the object Vault ⊗ SupplyQueue ⊗ w to the object Vault ⊗ SupplyQueue:

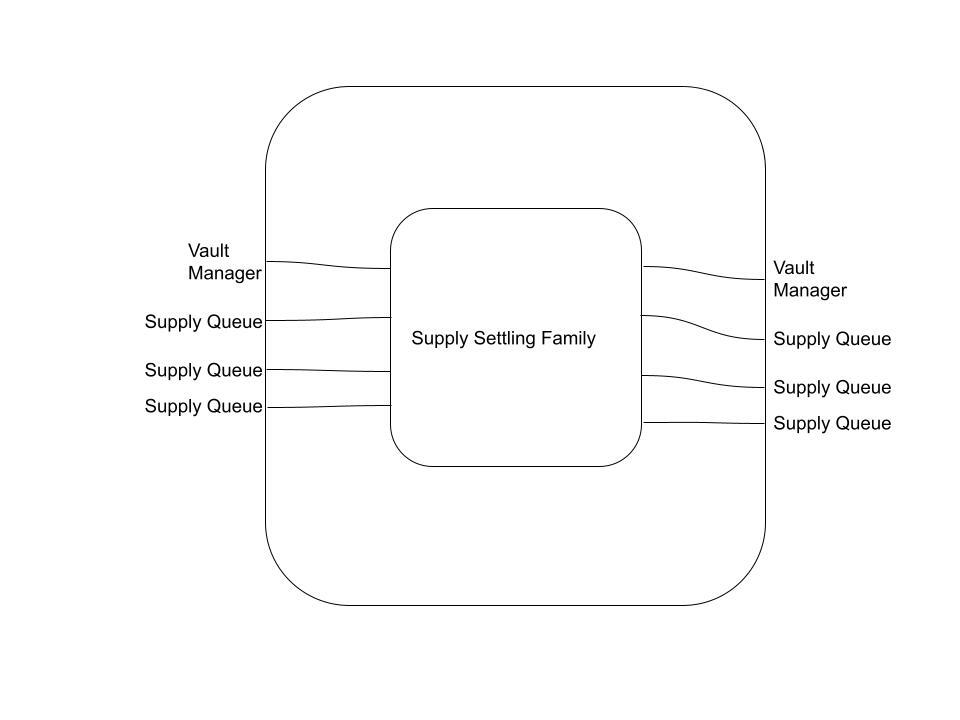

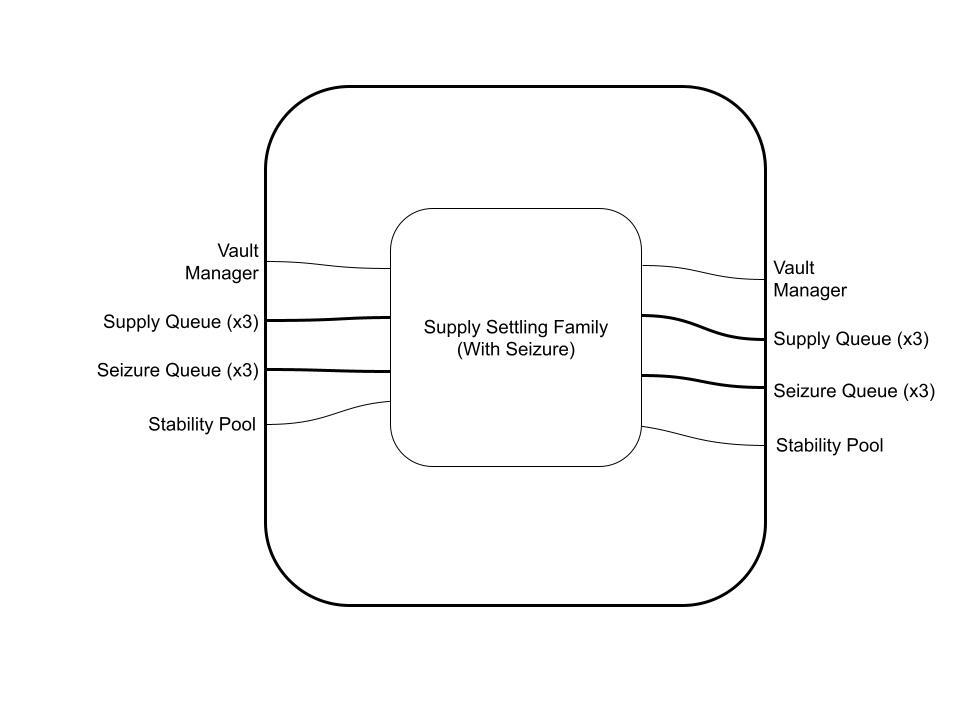

Next, the Supply Settling Family consumes three Supply Queue lane UTxOs and the Vault Manager UTxO, and produces the same. This has the effect of updating the global state of the Vault Manager according to the contents of the Datum of the Supply Queue UTxO, which carry information about queued adjustments to individual Vault debt and collateral balances.

The diagram below represents an endomorphism from the set G_tf from the object VaultManager ⊗ SupplyQueue ⊗ SupplyQueue ⊗ SupplyQueue to itself.

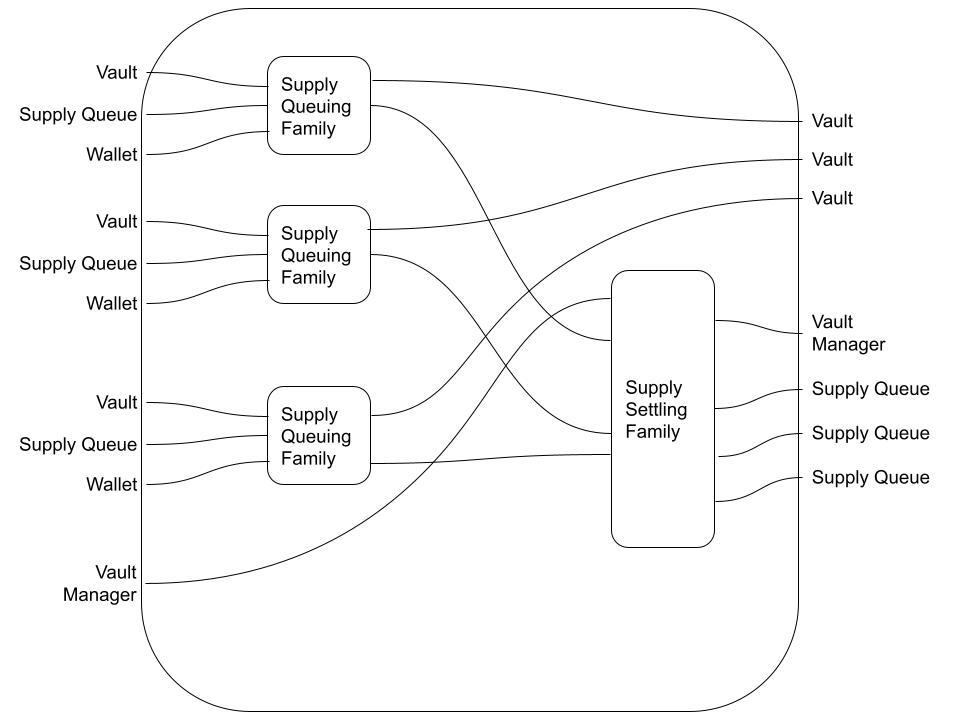

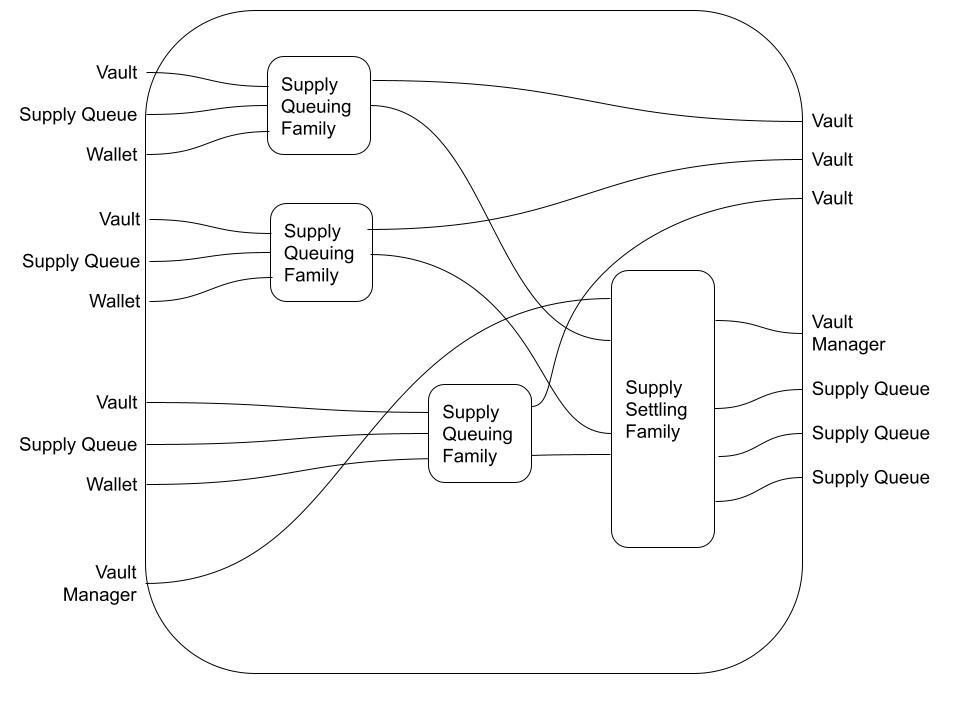

Now we can think of our first transaction flow, the "Supplying Flow". What we want is to consume 3 Vaults, 3 empty Supply Queue Lanes, 3 Wallets, and the Vault Manager, and produce 3 updated Vaults, an updated Vault Manager, and 3 fresh Supply Queue Lanes.

This level of "black box" reasoning can be represented as below. Note that we'll use Wallet instead of w from now on, to aid the reasoning process a bit.

Note that, in category theoretic terms, what we're doing is declaring the existence of a morphism from the objects on the left to the objects on the right. This morphism isn't inherently "special" in any category theoretic sense, except that it can be built up from morphisms in the generating set G_tf.

Using the two transaction families we already have, we can give one possible morphism as:

Recall that the vertical stacking of boxes in the monoidal product on morphisms, an empty line represents the identity morphism, and the horizontal arrangement of boxes is composition. Thus, if we adopt the following conventions:

fthe Supply Queuing Family morphism,gis the Supply Settling Family morphism,id_cis the identity morphism on componentc, andV, SQ, w, andVMare components with the obvious initials

we have the diagram above representing a morphism

(f ⊗ f ⊗ f ⊗ id_VM) ; (id_V ⊗ id_V ⊗ id_V ⊗ g)

from the object

V ⊗ SQ ⊗ W ⊗ V ⊗ SQ ⊗ W ⊗ V ⊗ SQ ⊗ W ⊗ VM

to the object

V ⊗ V ⊗ V ⊗ VM ⊗ SQ ⊗ SQ ⊗ SQ.

In this case, all three Supply Queue Lanes are filled in the same block, followed immediately by a Supply Settling Family transaction at some later time.

But this is not the only way to fill in the black box:

In this case, two supply lanes are consumed in one block; the last supply lane is consumed in a later block; and finally, all three lanes and the Vault Manager are consumed in a Settling Transaction.

This highlights that Flows are semantic equivalence classes of morphisms. When we present as Flow as a wiring diagram, we are saying "this morphism is an example of a morphism in the given Transaction Flow". In category theoretic terms, we can declare the equivalence of morphisms if we wish.

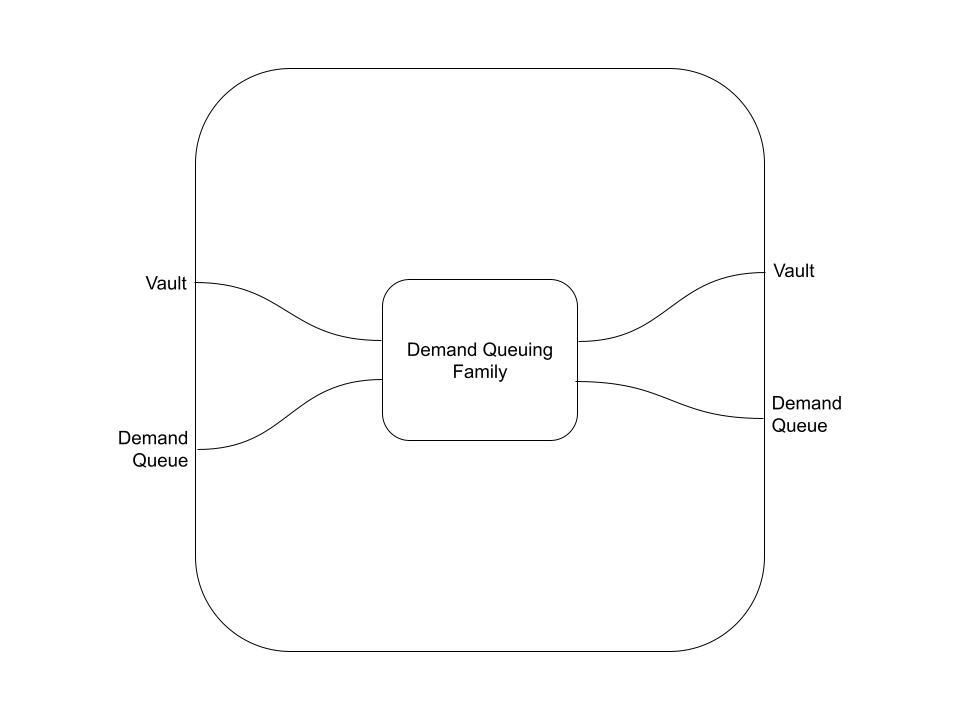

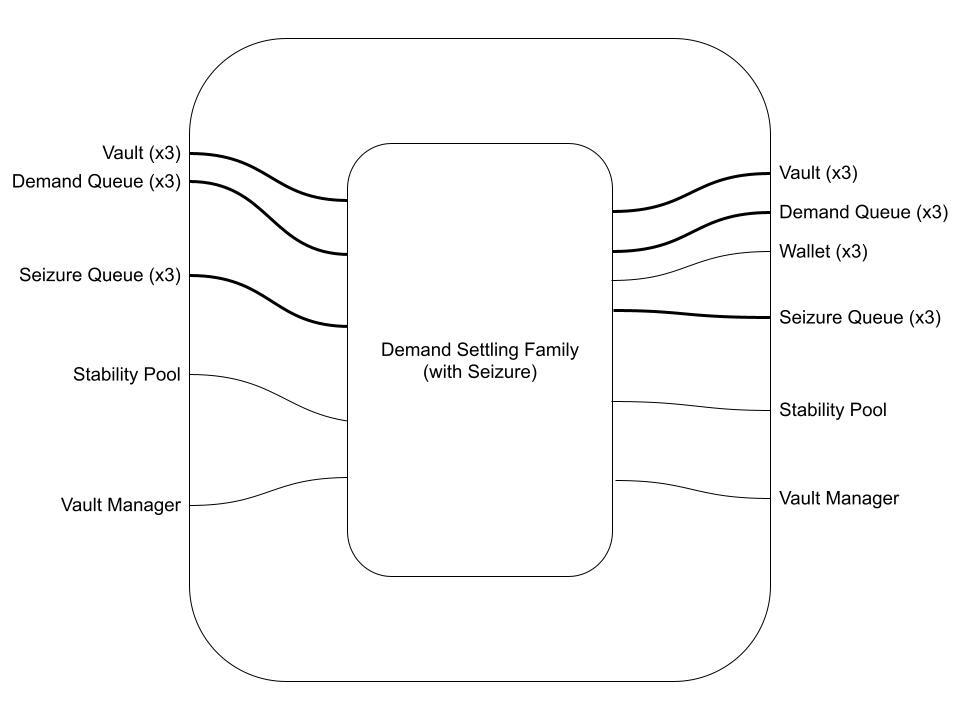

On the demand side, we have the Demand Queuing Family. The details are deliberately light, because (hopefully) a picture is worth a thousand words. See if you can understand what this does, using only the above description and the wiring diagram:

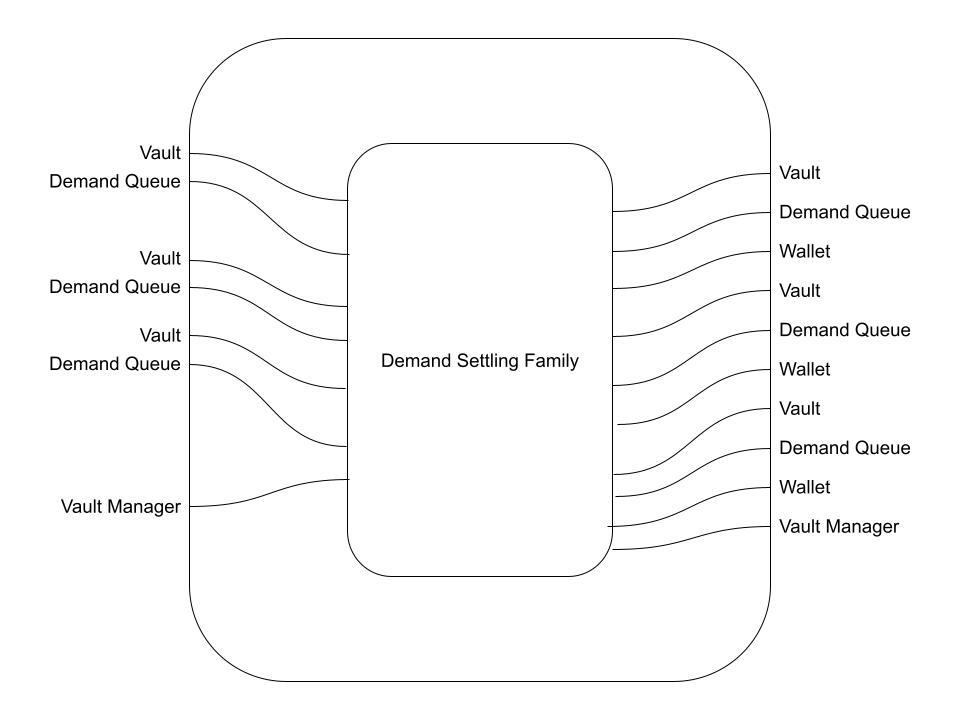

Same for the Demand Settling Family:

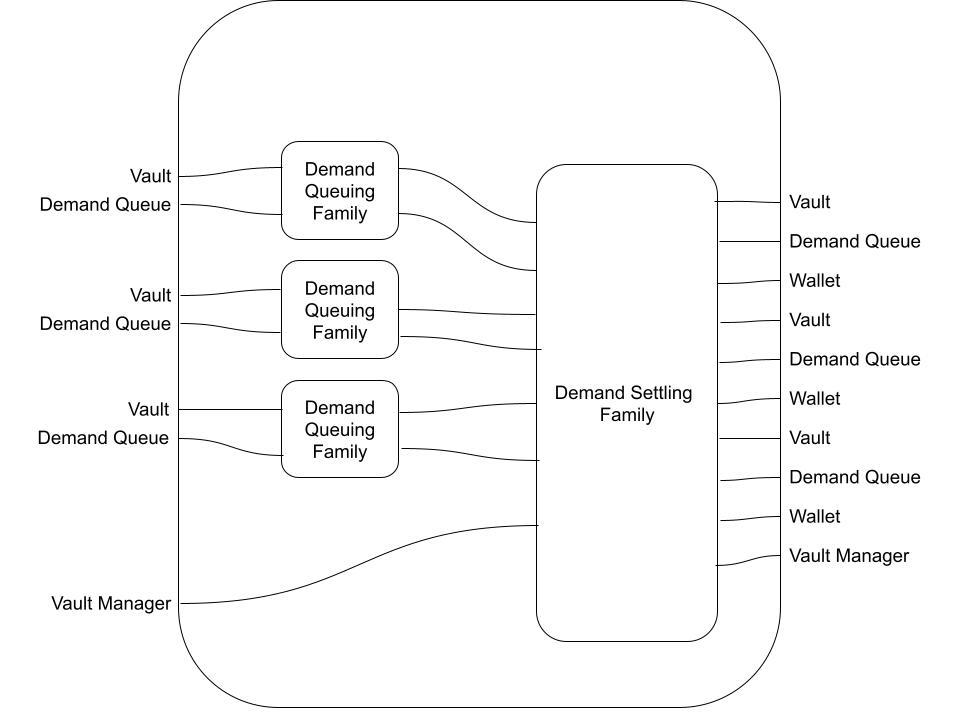

And finally the a Demand Transaction Flow morphism:

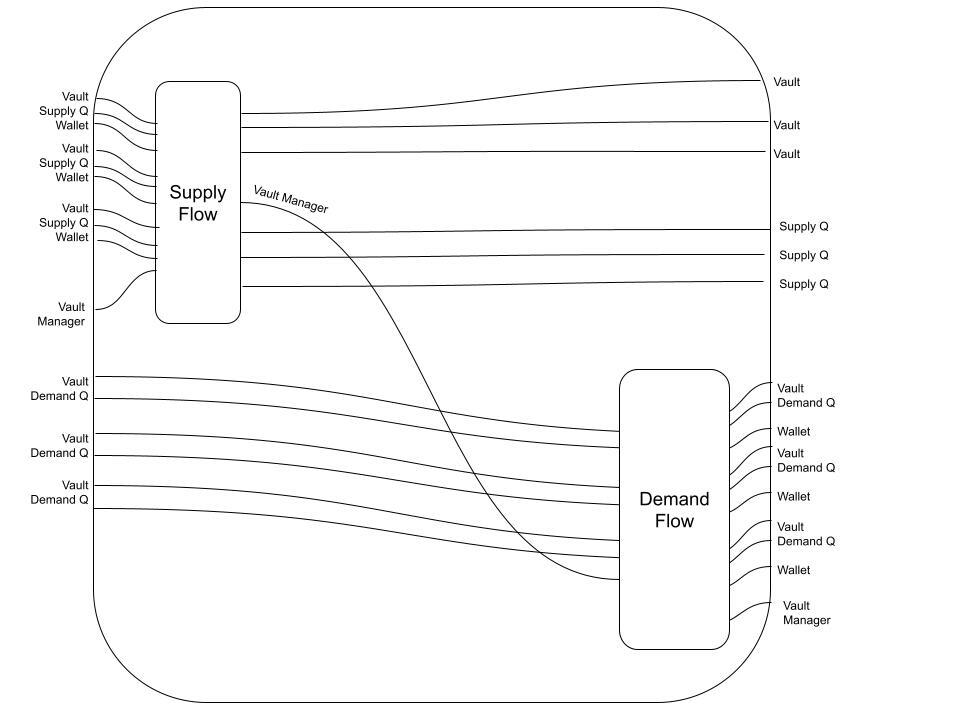

This is where things get interesting: composing the Supplying Flow with the Demanding Flow gives the Borrowing Flow. But since we already know what the Supplying Flow and Demanding Flow look like, we don't have to include the details of the Supply/Demand Queueing/Settling components to make sense of the following diagram:

The Borrowing Flow diagram represents a significant portion of the protocol's logic in an intuitive yet formal way that is highly amenable to both specification and implementation.

The Transaction Token Pattern gives a way to implement the building blocks (the morphisms, identified with the bijection between simplex Transaction Families, TxTMPs, and Contracts).

Wiring the blocks up is equivalent to the "routing logic" of the Validators. It may require (for instance) distinguishing between the "Supply Phase Vault Manager" on the boundaries of the Borrowing Flow and the "Demand Vault Manager" internal to the Borrowing Flow (ready to be consumed by the Demand Flow). This could be done either by carrying a flag in the Datum of the Vault Manager UTxO and adding some routing logic to authorize forwarding to the appropriate TxTMP, or by creating separate Validators for each Phase that only unlock for their specific flow.

Such capabilities could easily be abstracted into frameworks that mostly handle the wiring for you.

Finally, these types of diagrams make three situations extremely apparent:

- Transactions that "initialize" a component (such as bootstrapping the Vault Manager or opening a Vault for the first time) will always take the form of having an output on the right that does not appear on the left.

- Transactions that "continue" a component will have at least one of the same inputs on the left as an output on the right

- Transactions that "discard" a component will have an input that doesn't appear at the output.

This means that a transaction family or transaction flow can be analyzed in terms of the progeny of it's components. For example, the Demand Queueing Family requires the existence of a Vault and a Demand Queue UTxO. None of the wiring diagrams above "initialize" a Vault or Demand Queue UTxO, so we know that we need to specify them. Further, we know that there exists some other transaction flow that could compose the Initializing Flows with the Borrowing Flows.

The Protocol Category concept and TxTP Architecture lends itself to cleanly delineated boundaries of data and logic and promotes modularity and extensibility.

Suppose that we wanted to add a feature to the above flow, such as collateral seizure (for pull-based redistribution/liquidation of under collateralized Vaults). To do so, we can reuse transaction families that we've already specified, add semantics to other transaction families, and add some additional data to our Validator Datums.

In the event that we have already launched the protocol above, we would need to swap out TxTMPs with the new application logic and force a datum update where components require. Implementation wise, this would be dependent on the routing logic and would need to be carefully authenticated for most use-cases (and a good usage of governance).

This part is still a bit shaky, but from the category theory side such an upgrade seems to take the appearance of a functor between protocol categories: old objects are mapped to new objects, and old morphisms are mapped to new morphisms. Spivak and Fong represent database migrations with Adjunctions in Seven Sketches; this is probably the level of formality we're looking for, but I'm hazy on the details.

The basic idea of collateral seizure in LiqwidX is as follows:

- Borrowers must maintain an "Individual Collateral Ratio (ICR)" above a certain threshold (say, 120%). This means that the dollar value of ADA locked in their Vault divided by the dollar value of their outstanding debt must be no lower than 120%. Changes in the USD-price of ADA can cause a Vault's ICR to dip below this threshold.

- Vault's with collateral ratios below this threshold are said to be in default. They are subject to collateral seizure, which means that their debt is forgiven and their collateral is seized by the protocol. Since the ICR threshold is above 100%, this is a loss for the borrower.

- Once a defaulting Vault is seized, it is either liquidated, redistributed, or both.

- Liquidation means that preregistered parties can purchase the collateral at a discount. The Stability Pool is a way to preregister interest in purchasing collateral by staking LQUSD. When a Vault is seized, the collateral is first offered to the Stability Pool, which automatically offsets the outstanding debt by burning the LQUSD it holds. Then, an amount of seized collateral proportional to the amount of LQUSD burned is held in the Stability Pool as a clearing house. The seized collateral can be withdrawn by Stability Providers (i.e., LQUSD stakers), who typically receive a net gain by purchasing at a discount (with the spread being the difference between the Vault's ICR at the time of seizure (usually close to 120%) and 100%.

- Redistribution happens when the Stability Pool does not contain enough LQUSD to fully offset the debt of the seized Vault. In this case, the seized collateral is sent to the Vault Manager as a clearing house, and is subsequently redistributed across other Vaults along with a proportional amount of the outstanding debt. This typically represents a net gain for the targeted Vaults, which benefit from the same spread as the Stability Providers.

Both liquidation and redistribution are pull-based, meaning that the actual funds are held in a clearinghouses (Stability Pool for liquidation, the Vault Manager for redistribution). Each time a Stability Provider updates their stake, their outstanding collateral rewards are pulled into the their wallet. Each time a Borrower updates their Vault, any outstanding debt and collateral allocated to their Vault for redistribution is moved from the Vault Manager to their Vault.

Since we need to potentially push debt and collateral from a defaulting Vault into either or both of the Vault Manager and Stability Pool, we know we'll need to have these validators in the domain of some transaction family. However, since we already have two transaction families where the Vault Manager is updated (the Supply Settling and Demand Settling Families), let's add the Seizing Logic into those as a first approach.

First, we'll queue up any of our seizures using the Seizure Queue. We do this to make sure that all queue lanes are consumed each time each time that a batch of Seizures is processed, so that a transaction cannot be submitted which maliciously leaves out a Vault that should be seized. Implementation-wise, what this will look like is as follows:

- The first step in a Seizing Transaction Flow will be consuming a Vault along with with a Seizure Queue UTxO. The Vault's debt will be recorded and all collateral will be transferred to a new Seizure Queue UTxO, which prepares it for transfer into the Vault Manager/Stability Pool clearinghouses.

- The second step will be to process the Seizures. We've decided in the first approach to try adding this logic to the Supply/Demand Settling, so we'll just add the outputs of the Seizure Queuing into each of those.

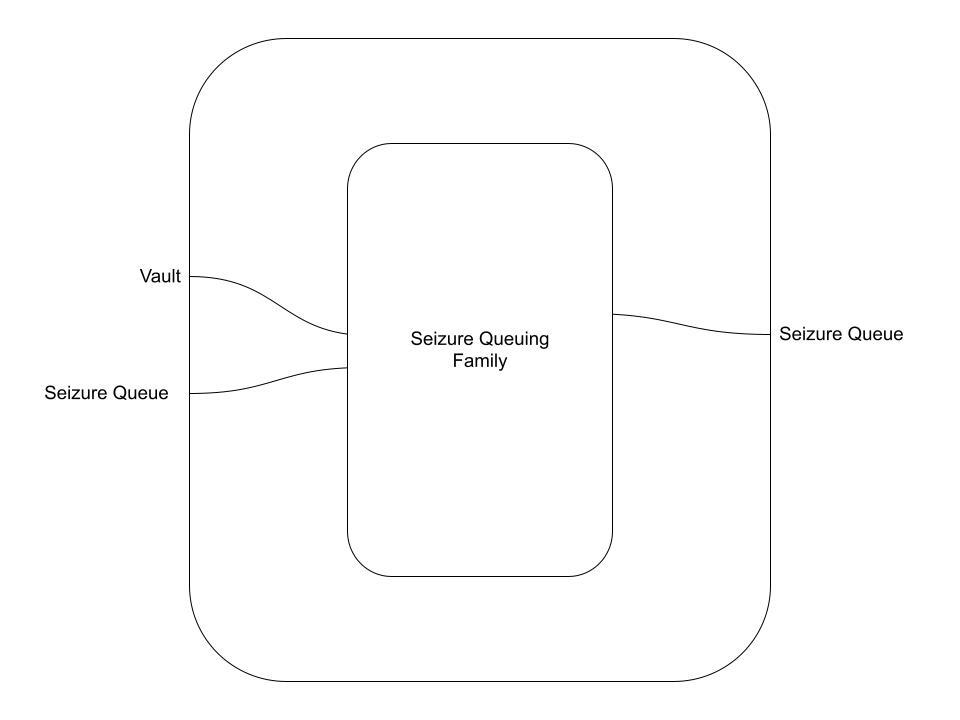

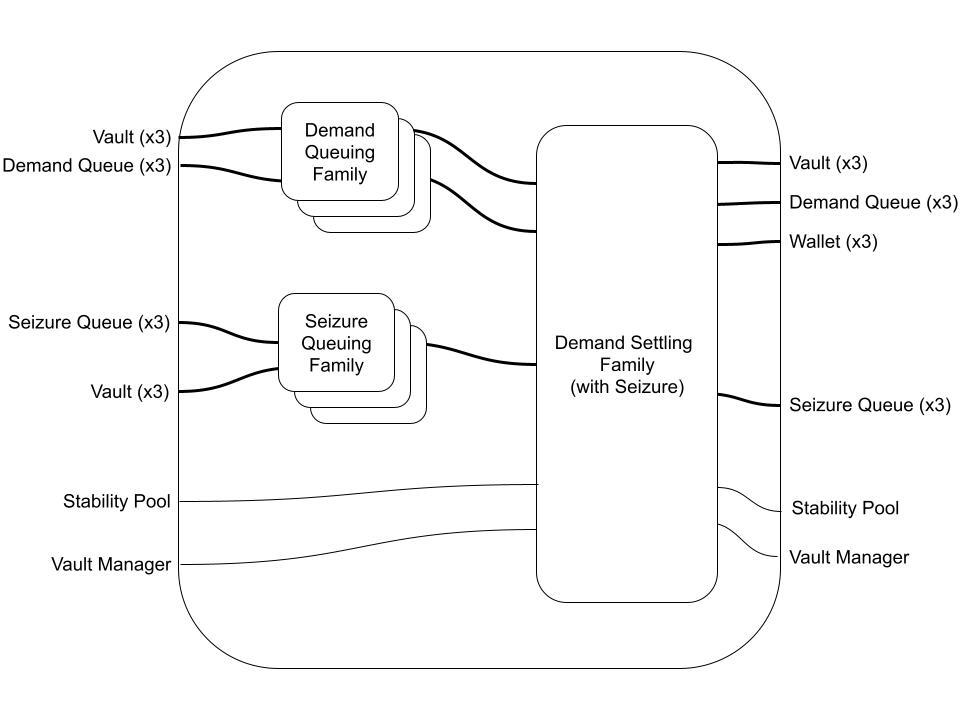

First, we make a new transaction family:

Next, we update our Settling Families. We simply consume three Seizure Queue Lanes, perform the Seizure (moving seized collateral and debt to the appropriate entity, if applicable) and produce three new Seizing Queue Lanes:

Implementing this would require writing the new logic, and the swapping out the old Settling Family TxTMPs for the new.

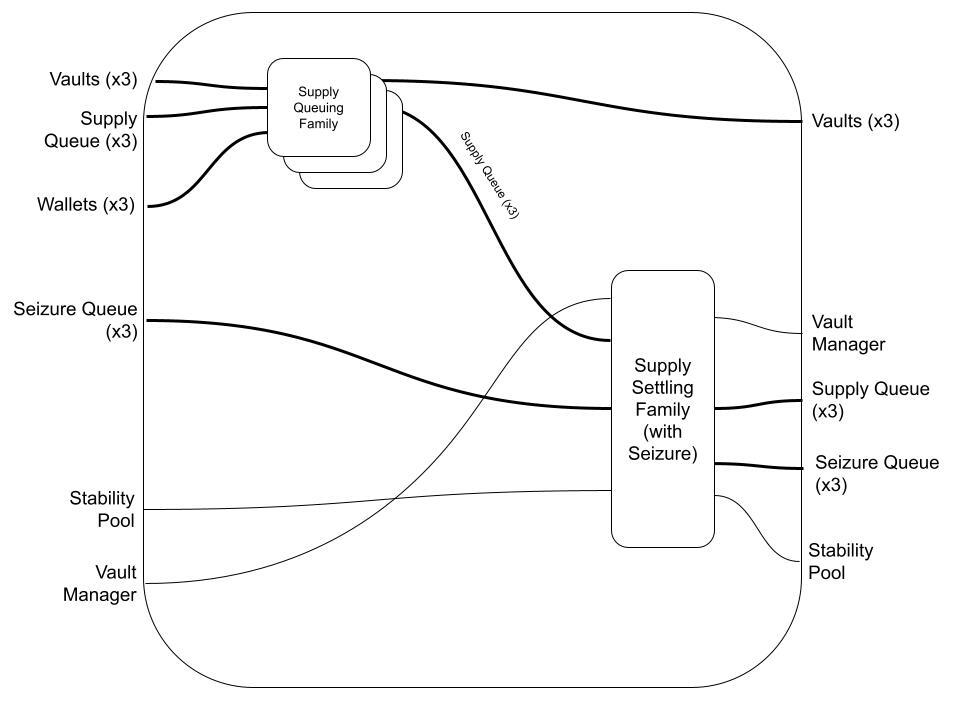

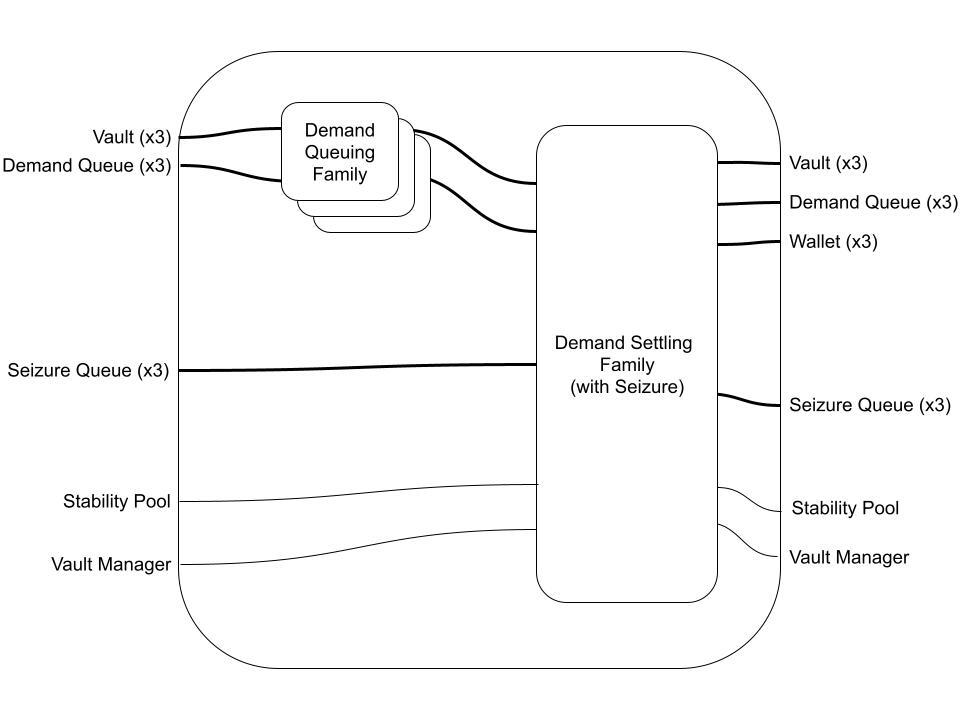

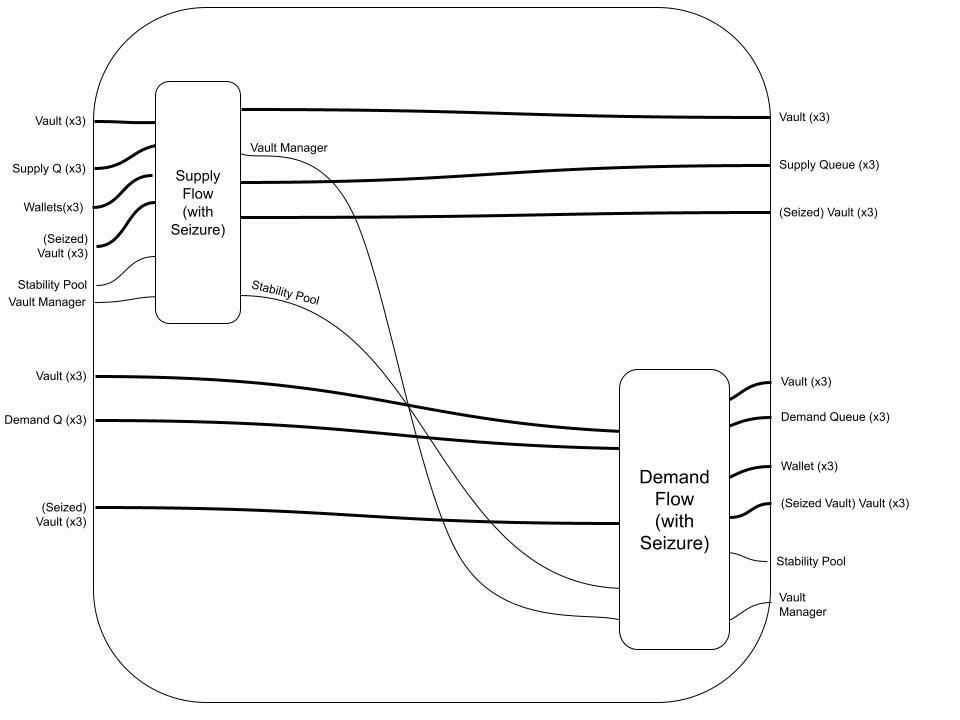

Both of these families form part of their respective Supplying and Demanding Transaction Flows. Let's take a look at what the new Flows look like:

So far so good. Notice we didn't have to modify the Supply/Demand Queuing Families at all. In practice, we may be required to make minor adjustments, since the routing logic may change or new data may need to be added to the Vault and Queue datums. But this still exhibits nice compositional properties, and presents a very intuitive graphical representation of the new protocol state.

Also notice that we described the Flow as taking in a Seizure Queue (that is presumably already filled), but we didn't specify that a Seizure Queuing Family transaction occurs in the same block as the Demand Queuing Family. This highlights that the wiring diagram representation of a Transaction Flow only represents a single permissible composition of Transaction Families, and does not capture every permissible composition. An alternate Flow could be represented, for example, as:

Both of these are permissible compositions. We'll use the first version for now.

Finally, we can update the Borrowing Flow.

And that's it. We've just added an entirely new feature to our protocol specification, and should have a clear idea of what we need to update in terms of TxTMPs, Contracts, Validator Datum types, and Validator routing logic. Additional, since clear boundaries were drawn from the start, the development should be easily distributed across a team; we can specify solid interfaces, prove invariants, and implement accordingly.

We could use a similar process to then add fees to the protocol or a DAO/governance. Another transaction flow can be designed for Stability Providers, including Staking and Rewarding. We have clear entry points to implement special protocol modes like "Emergency Shutdown" or "Recovery"; decide whether this needs a new Transaction Family or can be bolted onto an existing one, decide whether we need new application or component-level data, and update accordingly. Transaction Families and Flows could be modeled for protocol updates and modifications, or could be designed to dynamically configure the protocol according to some metalogic.