- RST, MD, LaTex

- Git

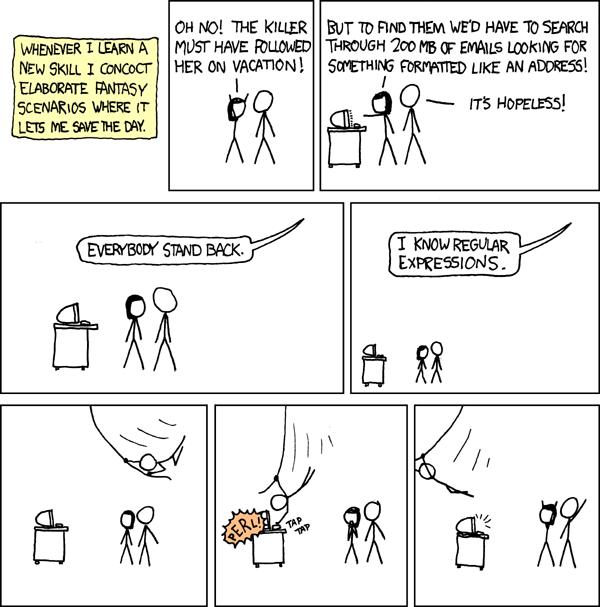

- RegEx

- SQLlite

- GNU Parallel

- Python

- Make

There are many suggestions of what sorts of software tools should be used by researchers. This includes some fairly obvious suggestions like Google Scholar or EndNote(TM), but of course that is the sort of thing that is by all researchers these days. Indeed, there is a bit of a challenge to distinguish between a "Researcher" and an "eResearcher", and the observation has been made that the latter is fairly widely used in Australia and New Zealand (where there are dedicated conferences with such a title), but not so much in the rest of the world.

In an attempt to make the difference, an eResearcher specifically uses with electronic data, and reviews, extracts, and manipulates that data in some fashion that would not be viable by hand. There is an implicit association therefore, with issues related to "big data". In addition there are also the new educational methodologies such as "connectivism"; a collaborative research model mediated by communications and information technology.

Research comprises "creative work undertaken on a systematic basis in order to increase the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of man, culture and society, and the use of this stock of knowledge to devise new applications." OECD (2002) Frascati Manual: proposed standard practice for surveys on research and experimental development, 6th edition. Retrieved 27 May 2012

It is used to establish or confirm facts, reaffirm the results of previous work, solve new or existing problems, support theorems, or develop new theories. A research project may also be an expansion on past work in the field.

A version control system allows for changes to a file to be recorded, allowing for reversion if necessary. Whether a researcher is dealing with datasets, documents, or code this is obviously a very valuable tool. Not only can individual files be reverted to a previous state, so could an entire project. Further, assuming the use of plain-text, it is also possible to compare changes and, in a shared document collection, who made their changes. Compared with merely saving files, even with a datestamp (e.g., included in the file name) a version control is a much superior means to control data. It is, for example, very common to modify a file after the datestamp and not record the new change independently. The earliest version control systems, such as Source Code Control System (SCCS), developed by Marc Rochking in 1972 included all the key features of revision control.

Another issue is that often groups of people which to collaborate on one or more files. A version control system in this case has to have a centralised repository, thus leading to various Centralised Version Control Systems (CVCSs). This includes older products such as Revision Control System (RCS), Concurrent Versions System (CVS) and relatively more recent systems like Subversion, which is still in active development. In this model the single repository holds all the versioned files and a users have a checkout and checkin process for the various files. The main problem with CVCSs is that the centralised repository is a central point of failure. If, for some reason, that centralised repository fails then the repository is lost (except if local snapshots have been made).

In more recent years, Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCSs) have been developed as a way around this problem. With a DVCS one doesn't checks out the latest snapshot of files, rather they checkout the entire history. If the centralised repository is lost, for whatever reason, the entire repository can be restored by any user. Essentially it is a peer-to-peer, rather than a client-server model of versioning control, and allows for one to develop even when not connected to a network, which means that changes can be made independent of network latency. DVCSs also have the possibility of having more complex versioning workflows that simply aren't possible on CVCSs. DVCSs include products like BitKeeper, GNU Bazaar, and Mercurial, but the most famous product of this sort is Git, originally developed by Linus Tolvards in 2005, and the most famous repository host is github. As a result, these will be the examples used throughout this chapter.

Most version control systems are orientated around storing information as changes to files. This makes some sense, because it from a first impression it is files that are changed. In git however, data is treated more like a filesystem. When changes are made, through a commit or other state change, git stores makes a snapshot and make a reference to that snapshot. If there are no changes, then the reference is applied to a previous snapshot. Further, git makes extensive use of checksums to ensure that changes are referenced. Information can't be changed or lost without git detecting the change.

There are three main states that files reside in the git environment; committed, modified, and staged. Data which is committed means that it stored in the local database. Data which is modified has been changed but has not been committed to the database. Data which is staged means that a modified file has been marked to be committed.

It is useful to conceptually associate the stages with the main sections of a git repository; the git directory, the working directory, and the staging agrea. The Git directory is where Git stores the metadata and object database for the project, and the working directory is a checkout of (active) version of the project is located. These are taken from the database in the git directory for use and modification. Finally, the staging area is a file that stores information about what will go in the next commit.

The basic workflow of git involves: (1) modifying files in a working directory., (2) staging the files and adding snapshot to the staging area., and (3) running a committ, which takes the files from the staging area and storing the snapshot permanently in the git directory.

For a Linux system, the simplist way to install Git is to use package management tool, which will vary according to the distribution. If one is using a RedHat-derived system (RHEL, CentOS, Fedora) one could use: sudo yum install git-all. For a Debian-derived system (Debian, Ubuntu, Mint) the equivalent would probably be: sudo apt-get install git-all.

For MacOS there are a few options. Apple has its own fork of Git (http://opensource.apple.com/source/Git/), although there is lag with the mainline version. A better alternative would be to make use of the Xcode Command Line Tools; simply by trying to run git will initiate the installation process.

Installation from source or on a MS-Windows system is not addressed here [EDIT]

Problem: git pull error: “error: insufficient permission for adding an object to repository database .git/objects” Solution: $chown [current-user-name]:[group-name] .git/objects -R

Drake Asberry / dasberry@email.arizona.edu / he/him/his / @AsberryDrake / @drakeasberry Tobin Magle/ tobin.magle@wisc.edu / she/them / @tobinmagle Preethy Nair Abhinav Mishra/ mishraabhinav36@gmail.com/ he, him / @shadytoyou (Twitter) Notes: This workshop is essentially the continuation of the SWC Git lesson: https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/

Picture from class is on GitHub: https://github.com/chendaniely/2020-07-16-CCatHome-git-dan/blob/master/whiteboard.png

Carpentries blog post on how to fix someone's PR: https://carpentries.org/blog/2020/04/maintainers-git-skills/

Software Carpentry notes on basic git: https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/ The setting up git has the commands to setup your name/email/editor: https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/02-setup/index.html

Review of cloning a repository and pushing a commit Best workflow: create empty repository on Github/BitBucket etc, then copy ("clone") to your computer This workflow ("cloning a repo") is not covered in the Software Carpentry instructions as it mainly shows how to create a Git repo locally and link it to Github. We will be doing "Github first". We start with creating a new repository, give it a name "2020-07-16-CCatHome-git-[yourname]" Leave the as repo public, click "Initialize with README" Click the "Code" button and copy the HTTPS URL Open up the Terminal or shell in your local computer Don't clone git repo into another one! Make sure you don't have nested git repositories (just like "git init" you only do it once ever) Dan recommends creating a folder called "git" in your root directory, then cloning things into there To open your Finder in Mac / file explorer in Windows, type "open ." or "explorer ." or "xdg -open ." in Linux To clone, "git clone [URL]" = downloads the repo from the web cd into that directory nano README.md -- add some notes about what you're doing git status git add README.md git commit -m"talked about git clone" git remote -v (this shows the remote Github URL) git push origin master Branching / Making a branch: Why use a branch? It enables you to go back to a pre-defined point before you try some experimental things, and it allows you to collaborate confidently without! Branch = A label for a series of commits git --version (some of the prompts in the newer version are going to be a bit different - you don't have to update Git now - or ever! - but the prompts may not be the exactly the same, FYI) git branch my_first_branch (create a branch) git branch -a (list all branches, the one that is green/has a star next to is the one you're on) git status (you see that "On branch master" is the branch you're on) git log --oneline --graph --decorate --all (this shows you the entire tree) git checkout my_first_branch (standard way to checkout branch), new command is git switch my_first_branch (git switch will only work if you installed Git after August 2019) Repeating the push workflow... nano README.md (let's add a note to the README about what we learned) git status git diff README.md git add README.md git commit -m "A commit on a branch!" git log --oneline --graph --decorate --all (this shows you the entire tree) you can make this shorter by creating git aliases https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Basics-Git-Aliases git config --global alias.l "log --oneline --graph --decorate --all" git push origin my_first_branch (note that it's not "origin master" - if you're not used to working with branches, you may be tempted to type "origin master") Good tip from Dan: if you can draw out the Git problem you're having visually - on a whiteboard, chances are you can figure out the command you need to fix things! We then merged a PR from our branch into master, issuing a review on Github in the process, then deleted our extra branch Pulling our merged changes from Github: cat README.md git pull origin master

Exercise 1

-

create a new branch

-

go to the new branch

-

edit README.md with text (talkl about fetch --prune, and the log command and deleting branches )

-

push branch to github

-

create pr

-

merge PR

-

update and clean up your branches on local computer

Exercise 1 answers: git checkout -b creating_branches (this allows you to create + switch to the branch in one go) nano README.md (open up text editor to add a note) git fetch --prune (will update your local git tree with the remote. this will also delete references to branches that were deleted on the remote) git stash (saves your temp changes when you switch branches) git stash apply (apply your stashed changes) git add / git commit / git push workflow Merge PR on Github to master (you can even leave yourself a review!), then come back to local shell to pull changes and delete branch git checkout master git fetch --prune git branch -a git pull origin master git branch -d creating_branches (delete local copy of remotely deleted branch) When someone needs to make changes to their PR, they can continue to work on branch, do not need to create a new PR When you merge PRs, you generally want "create a merge request" aka the default - "squash and merge" creates pretty commits, "rebase and merge" is useful when you have merge conflicts

Rebasing This is useful when you have merge conflicts git rebase git rebase --abort (will bring things back to normal, safety hatch for rebasing) git rebase --continue this takes care of what is on your local computer to update on your remote (on github) - can't use git push origin change_title_2 this will give you an error because the history is different, but this is actually what you want to do, so use -f (force) flag git push -f origin change_title_2 then do your cleanup steps git pull origin master git fetch --prune git branch -d change_title_2

Different workflows Centralized workflow - everyone who is working on the project has merge access! Problem with this is that everyone is working on the master branch. No enforcement of code review. Can enforce code review on certain branches in GitHub settings Feature branch workflow - no one can push directly to master Requires code review Git flow - standardized way of naming branches master branch stores official release history - tagged with version number develop branch serves as integration branch for features most work happens on develop branch Forking workflow - Requires most collaborators to fork rather than branch This is the workflow used on Carpentries lessons People who don't have write access can't make branches, need to fork Forking creates a copy of the repo in their own GitHub account - you can do whatever you want with this copy Common model for open source projects Naming conventions: origin = the remote repository you have push access to upstream = the remote repository that you forked from To keep your fork in synch with the official lesson repo - you pull from upstream and you push to origin (and then submit a pull request to upstream)

Using forking workflow: Create a fork of the repository you want to work with (top right corner "fork" button) Clone to your computer - click "Code", copy the ssh url, in terminal "git clone " Set the upstream by using git remote add upstream Now work as you would normally

Questions from participants: Could you please explain branching v forking? Not the how, but the why? We have about half who like to fork and half who like to branch and I don’t get why some folks do one over the other. Forks are copies of the repo in your own account. Mandatory if you’re not part of the organization that owns the original repository. I had to fork to submit my pull requests for checkout. i am getting an error message on switch / "git switch" doesn't work for older version Nope, you can use git checkout instead :) git switch is a new function and only works if you installed Git after Aug 2019 should we update git? can’t believe i never even considered it... If you want to use git switch, maybe! A currently important question for me right now: can I rename my git repo locally and then still push it to my remote origin that still has the same name? Yes, if you cloned from Git, I think Git has the remote URL stored…(see git remote -v) I know the other way around works, too! You’ll just get a message warning you and telling you to change the name\00l

A good workflow for renaming: git remote -v git remote rm origin git remote add (the one you copy from the green button on the repo) The official way to do it: git remote set-url alias url, Or: git remote set-url <>` will update origin There is a large controversy over git pull versus a git fetch then git merge within my collaboration circles. Is there a benefit too doing one over the other? git pull does both, generally good enough for all purposes git fetch / merge is if you need to delete references or get references to something (a little more manual) Question - I know that git has some automatic assumptions about what origin and master are if you just do “git pull” or “git push” without specifying. Could you talk about what that is and whether we should use that? I admit I always just do a bare “git pull” or “git push” without specifying origin and master. Should I? There is no difference when you're working on master. If you're just working on master and not branches, just use git push/pull without "origin master" bit However, when you're on a branch, get into the habit of not relying on the default. This forces you to slow down and think, what am I actually doing Question - is your fork your remote? Yes - your fork becomes your remote! Will talk about naming conventions for remotes soon. Question - I’ve never actually set the upstream when working with the fork workflow on a Carpentries lesson, and everything seems to work . . . (I usually make changes locally, then push to my fork, then make a PR on GitHub). Is there a reason to set the upstream?\00i

Notes / resources from participants: Working tree, staging, repo: https://medium.com/@lucasmaurer/git-gud-the-working-tree-staging-area-and-local-repo-a1f0f4822018 For Carpentries lessons - all Maintainers for that lesson have merge permissions :-)\00 And we’ve also implemented automatic branch deletions after resolve, so you don’t need to worry about deleting branches

Git workflow notes and commands (to paste on your wall) https://chendaniely.github.io/training_ds_r/help-faq.html Atlassian page on git workflows: https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/comparing-workflows

Some nice things to look up to get a nice pretty terminal prompt: Getting your (bash) terminal to show current path and other things: Use this to create your PS1 variable: http://bashrcgenerator.com/

Show git branch in terminal: In addition you can write a function and put that in your PS1 to also show git branch https://gist.github.com/joseluisq/1e96c54fa4e1e5647940

git log --oneline --graph --decorate --all

Why do UNIX-like operating systems make extensive use of text files?

ASCII plain-text is a simple format that is accessible to many tools. Unlike other file formats (e.g., various binary files) text does not have to worry about padding bytes or whether it is ordered against most or least significant bytes in memory (endianness), making them adaptable across different computer architectures. If data corruption occurs, it is easier to recover the remaining data. For users, a very significant advantage is the fact that basic tools in the operating system make use of text files including those in regular expressions (e.g., grep, sed, awk) and, of course, they are readable by the human user which is important when dealing with source code. Plain text can be encoded by an application, but unless the application is available, decoding can be challenging. As a result of all these features, text files can persist over time much better than other formats. A disadvantage of text files is that can occupy greater storage than a compressed binary format. Note that binary executables are often larger than source code because they include the libraries invoked by the source code).

Consider the following passage from Thomas Paine's Agrarian Justice (1797).

"There could be no such thing as landed property originally. Man did not make the earth, and, though he had a natural right to occupy it, he had no right to locate as his property in perpetuity any part of it; neither did the creator of the earth open a land-office, from whence the first title-deeds should issue. Whence then, arose the idea of landed property? I answer as before, that when cultivation began the idea of landed property began with it, from the impossibility of separating the improvement made by cultivation from the earth itself, upon which that improvement was made. The value of the improvement so far exceeded the value of the natural earth, at that time, as to absorb it; till, in the end, the common right of all became confounded into the cultivated right of the individual. But there are, nevertheless, distinct species of rights, and will continue to be so long as the earth endures."

As a text file, this occupies 911 bytes of data (ls -l agrarian.txt). If this is saved as a binary image file in the png format (mainly due to ignorance, sometimes due to malice, people do save text as images) it occupies 76777 bytes (ls -l agrarian.txt). One cannot search the text either with standard utilities nor select and paste parts into different documents etc. Whilst text readers are ubiquitous across operating systems and computer architectures, png is a relatively recent format and requires an executable application that can read such files. If compressed the text file will be smaller still (e.g., tar cvfz agrarian.tgz agrarian.txt, ls -l agrarian.tgz, 911 bytes vs 200 bytes). However, it is not very readable:

$ cat agrarian.tgz �9W�a��α�P���+� ��٪���`�����r��>�Ht�Աm6F|�,���Y�ǧ�y�Q�r}o��,]%�WX�[�^�k����Q��z����x� ����R[���O�?����?ɵ�_�f�8��Ѫ��Ϗ,��.�����#�������(

Whilst text files are an excellent format to store and express data, typically when one is analysing data they wish to find information. This is not something that is simply achieved when one is looking in a very large collection of text files. Searching for particular sequences of characters is a typical task, but there are often rules included in that task, such as a fixed string or whether it is preceded or followed by additional characters. Such searches and the manipulation of text are the subjects of discussion.

It must be mentioned that binary formats certainly do have their place. It is from binary formats of files associated with applications that visualisation often occurs, such as the file formats from molecular modelling or fluid mechanics. Often these are tied with text files for their initial state but the dynamic results of the simulation are stored in a binary format.

Regular Expressions ("RegEx") are general character pattern notations that provide the means for efficient and effective text processing. The main use is search, replace, and validation functions, which can - at least in part - be achieved through a variety of text editors. However, compared to various RegEx tools, using a text editor is a fairly labour intensive process. For researchers, especially those whose work involves a great deal of data extraction and manipulation, having a good grasp of regular expressions is one of the most powerful tools available.

The origins of regular expressions come from a combination of mathematics, linguistics, and computer science. The first formal development was by Stephen Cole Kleen who described a mathematical "regular language" in 1951 that would be located as a Type-3 grammar in the hierarchy developed by Noam Chomsky in 1956, which a finite-state machine will recognise.

Fun fact. Stephen Cole Kleene also wrote an alternative proof to Gödel's incompleteness theorems that were easier to understand. From this, it has been quipped that "Kleeneness is next to Gödelness".

A regular language is a language that with symbolic characters that concatenate into strings of the language and are well-formed according to a specific set of rules, and which can be defined by a sequence of characters that specifies a search pattern. Note that regular expression utilities contain additional searching features. The first major computational use was in 1968 through pattern matching in the QED ("quick editor") text editor. QED was originally written in 1965 and was designed for teleprinter usage. When Ken Thompson wrote a version for the Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) in 1968 a level of regular expressions was introduced. Around the same researchers, including Douglas T. Ross, implemented a regular expression engine in compiler design.

The regular expression system in QED was ported to ed in 1969 to become a foundation of the UNIX operating system. Within ed the function for searches was g/re/p, "global search for regular expression and print (to standard output). The functionality was considered so useful that Ken Thompson used the logic from ed and wrote the first version of grep overnight in November 1974.

Apart from grep, other major applications in the regular expression world include sed ("stream editor", 1974), AWK (named after its authors "Aho, Weinberger, Kernighan", a data-driven scripting language, first release 1977), perl (often given the common backronym "Practical Extraction and Reporting Language", first released 1987). Many other programming languages use regular expression engines, but the aforementioned are considered the main foundations

A major feature of RegEx is the use of metacharacters, which have a special meaning to the RegEx application over and above their literal meaning. For example the use of a ^ to represent the beginning of a line, or a * to represent any of 0 or more characters.

The POSIX standard (basic and extended) has some 14 metacharacters. In this standard metacharacters must be "escaped" (preceded by the backslash character \) to be considered in their literal meaning. Famously, this includes the backslash character itself, so in order to express a literal backslash one requires \\. The main difference between POSIX Basic Regular Syntax (BRE) and Extended Regular Syntax (SRE) is that the basic form requires the normal and curled bracket characters to also be escaped i.e., \(\) and \{\}.

The entire suite of metachaarcters that require an escape for their literal include opening and closing normal, and curled brackets, the caret, the dollar sign, the period, the bar, question mark, asterisk, the plus sign, and the backslash i.e. "(", "{" "}", ")", "^", "$", ".", "|", "?", "*", "+", "".

In addition to these metacharacters there are also metacharacters that are not escaped by the backslash. This includes the aforementioned normal and curled bracket characters and the - character which is used to indicated ranges within a square-bracket set. Searches for metacharacters in their literal form can also be conducted in a square-bracket set without being escaped (e.g., grep '[\2^] filename.

Metacharacters are so important to understanding regular expressions and so common across the core applications it is worth establishing a thorough understanding of them early. The following outlines the major metacharacters, their meaning, and an example using the search utility grep. Note that a metacharacter can have different meanings within regular expressions. The caret symbol, can either stands as beginning of a line anchor and a negation symbol in a set range. Like other *nix-like system this environment is case-sensitive. Metacharacters that are used outside of their context, even within a regular expression, will be treated as literal character.

Metacharacter Examples

| Metacharacter | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ^ | Beginning of string anchor | grep '^row' /usr/share/dict/words |

| $ | End of string anchor | grep 'row$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| . | Any single character | grep '^...row...$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| * | Match zero plus preceding characters | grep '^...row.*' /usr/share/dict/words |

| [ ] | Matches one in the set | grep '^[Pp].row..$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| [x-y] | Matches on in the range | grep '^[s-u].row..$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| [^ ] | Matches one character not in the set | grep '^[^a].row..$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| ` | ` | Logical OR |

| [^x-y] | Matches any character not in the range | grep '^[^a-z].row..$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| \ | Escape a metacharacter | grep '^A\.$' /usr/share/dict/words |

| < > | Beginning and end word boundaries | grep '\<cat\>' /usr/share/dict/words |

Note that the examples use strong quotes for search term to prevent the possibility of inadvertant shell expansion. If shell expansion, variable substitution etc is desired then use weak quotes. Note that the . is lazy (it matches any character, including those you might not want or need) and the * is greedy (it matches 0 or more preeceding characters).

In the chapter resources directory on github try the following on the file problem.txt: grep '".*"' problem.txt grep -o '"[^"]+"' problem.txt

The second example (grep, matching only, negate set of any characters except quote, add match at least once) is much more complex, but gives the right answer.

Metacharacter Class Statements

In addition to singular metacharacters there are also character classes, which take a common range statement. For example the class '[[:alpha:]]' is the equivalent of the range [A-Za-z] and [:punct:] is equivalent of [][!"#$%&'()*+,./:;<=>?@^_`{|}~-] . POSIX requires that classes must be expressed within square brackets, which does have the advantage to extend outside the class (e.g., [[:upper::]0] would match with all upper case alphabet characters and the number 0.

| Metacharacter | Explanation |

|---|---|

| [:digit:] | Only the digits 0 to 9 |

| [:alnum:] | Alphanumeric characters 0 to 9 OR A to Z or a to z. |

| [:alpha:] | Alpha character A to Z or a to z. |

| [:blank:] | Space and TAB characters only. |

| [:lower:] | Lower case characters |

| [:punct:] | Punctuation characters |

| [:upper:] | Upper case characters |

| [:xdigit:] | Hexadecimal digits |

Assuming that the requests are not contradictory metacharacters can be combined. For example, ^$ represents blank lines, ^firstword.*lastword$ would search for a line of text that starts with "firstword" and ends with "lastword" and contains anything in between.

Most basic use of a regular expression is searching text and the basic tool for this is grep which considered sufficiently important that the Oxford English dictionary has included entries for "grep" as both a noun and a verb. One will also find references to egrep and fgrep which included extended regex syntax and fixed strings. These utilities however have been deprecated and their funcationality is included in the command switches -E and -F respectively.

A typical formal structure is a search for a pattern with Boolean logic, grouping, quantification (e.g., number of instances), and wildcards, followed by an optional operation (arithemetic count, replacement etc) on the pattern. In a POSIX environment a command structure is application (options) RegEx file e.g., grep -i ATEK gattaca.txt. The command is invoked, with options, with a regular expression pattern on a particular file. The result is sent to standard output by default.

The usual action of grep is to search for a given string in one or more files with the standard syntax of grep "STRING" FILES (e.g., grep "ELM" gattaca.txt).

Grep with Metacharacters

Metacharacters can be combined in an interesting manner with grep options.

Some examples of grep options with metacharacters.

-

Print only the matched parts of a matching line with separate outline lines. grep -o '"[^"]+"' filename

-

Count the number of empty lines in a file, '-c' is count. grep -c '^$' filename

-

Search for words without standard vowels, '-v' is invert match. grep -v '[aeiou]' /usr/share/dict/words

-

Case-insensitive search for lines that start with QANTAS, and only QANTAS (not QANTAS1, for example), in all files in the specified directory, and specify the line number in the file(s) that it appears in. The options '-i', '-w', '-n' are case-insensitive, whole word, and line-number respectively. grep -iwn '^QANTAS' /usr/share/dict/*

Faster Grep

Localisation settings might slow down your grep search. Prefixing the search with LC_ALL forces applications to use the same language (US English). This speeds up grep in many cases because it is a singl-ebyte comparison rather than multi-byte (as is the case with UTF8). It is not appropriate if you are searching file with non-ASCII standard characters!

Use of grep -F (or fgrep) interprets the search pattern as a fixed string, rather than a regular expression - which means that one does not need any regular expression escape characters. If one is searching for strings rather than patterns this can be faster.

Examples:

time grep -i searchterm *

time LC_ALL=C grep searchterm *

time grep -F searchterm *

Multiple Greps

The option -l with grep will print only the name of the each input file which matches the regular expression. This can be used with xargs to search multiple files for multiple search terms.

Example:

Search through a directory of build scripts for those files that use the Tarball block, have an installstep parameter, and use the dummy toolchain.

grep -l 'Tarball' * -R | xargs grep -l 'installstep' | xargs grep -l 'dummy'

Parallel Grep

With GNU parallel or by piping find with xargs to grep, grep can be run in parallel.

This is especially useful when you have are searching through a lot of files or a large file.

For example:

time find . -type f -print0 | parallel -k -j200% -n 1000 -m grep -i 'searchterm' {} > output3

or

find . -type f -print0 | xargs -0 -P 8 grep 'searchterm' files > output

For big files, it can be split into chunks with the --pipe and --block options.

parallel -j200% --pipe --block 2M LC_ALL=C grep -F 'searchterm' < bigfile

As the name implies sed is a stream editor, which means it takes a data stream in a non-interactive mode, makes the changes according to a regular expression, and sends the results to

standard output. By default it does not change the original data stream, which is typically a file. It could be used to use the data stream source as input from a keyboard, but this would be an unusual use of the application. More typically it is used for massive and rapid search and replaces on a number of documents, various forms of data cleaning (e.g., removing trailing whitespace), or conversion from one type of text markup to another (e.g., from a wiki syntax to html or troff etc).

The general form is sed [OPTION] [SCRIPT] [INPUT]. Common options are e (multiple scripts per command), -f (add script file) and -i (in-place editing). By default sed sends results in standard output (i.e., the screen). If a change to the file is desired, use the -i option, and consider making a backup of the original by passing an argument. Or redirect output to a newfile. e.g.,

sed 's/search/replace/g' file

sed 's/search/replace/g' file > newfile

sed -i 's/search/replace/g' file

sed -i.bak 's/search/replace/g' file

Substitutions

Substitions are the most common command in sed. It changes data in the stream from one value to another, line-by-line. It's a 'search-and-replace' but with a regular expression language.

The general approach is sed 's/search/replace/g' file. Without the g (global) the substitution will stop at the first instance. Another common option is I for case-insensitive search e.g.,

sed 's/search/replace/gI file.

Try these commands with the gattaca.txt file e.g.,

sed 's/^/ /' gattaca.txt

sed '/ELM/s/Q/\$/g' gattaca.txt

| Command | Explanation |

|---|---|

sed 's/^/ /' |

Insert five whitespaces at the beginning of every line. |

sed '/baz/s/foo/bar/g' |

Substitute all instances of 'foo' with 'bar' on lines that start with 'baz' |

sed '/baz/!s/foo/bar/g' |

Substitute "foo" with "bar" except for lines which contain "baz" |

sed /^$/d |

Delete all blank lines. |

sed s/ *$// |

Delete all spaces at the end of every line. |

sed 's/$/\r/g' |

*nix to MS-Windows, adds CR. |

sed 's/\r$//g' |

MS-Windows to *nix, removes CR |

A popular list of one-line sed commands can be found at the following URL http://sed.sourceforge.net/sed1line.txt

See also books, scripts, games, and tools from "the sed $HOME" http://sed.sourceforge.net/

Printing and Deleting

The commands p and d print and delete the lines where a regular expression is found, respectively.

sed -n /ELM/p gattaca.txt

sed /ELM/d gattaca.txt

Without the -n it will output the file, gattaca.txt, and print the ELM line a second time.

With the d option it will output the file, gattaca.txt, with the ELM line deleted.

Adding the w option will print out the selection line to a new file.

sed 's/ELM/LUV/gw selection.txt' gattaca.txt

Quoting

Generally strong quotes are recommended for regular expressions. However, sed often wants to use weak quotes to include (for example) variable substitution. Consider for example, a job run which searches for a hypothetical element and comes with the result of Unbihexium. This is the equivalent of:

UnknownElement = Unbihexium

echo $UnknownElement

A file where the search term UnknownElement exists could be replaced with Unbihexium with:

sed "s/UnknownElement/$UnknownElement/g" filename

Another issue is conducting substitutions with single quotes in the stream, in which case double-quotes are an appropriate tool.

sed "s/ones/one's/" <<< 'ones thing'

Another method is to replace each embedded single quote with the sequence: ''', i.e., quote backslash quote quote, which closes the string, appends an escaped single quote and reopens the string.

The sed metacharacter, & can be used as variable for the selection term. For example, a list of telephone numbers could have the first two digits selected and then surrounded by parantheses for readability.

sed 's/^[[:digit:]][[:digit:]]/(&) /' phonelist.txt

A repeated term can be invoked with curly braces and a number representing how often the term should be repeated.

The above example could be re-written as:

sed -E 's/^[[:digit:]]{2}/(&) /' phonelist.txt

Selections in sed

Occurances and lines can be specified with sed. For example, the second instance of A can be replacd with T with the following command:

sed 's/A/T/2' simple1.txt

Or replace every instance after the second.

sed 's/A/T/g2' simple1.txt

Or only replace every instance after the second on the second line.

sed '2s/A/T/g2' simple1.txt

Or for specific lines.

sed '1,2d' gattaca.txt

sed -n '1,2p' gattaca.txt

sed -n '1,3p' gattaca.txt or sed -n 1,+2p gattaca.txt

sed -n '1,3!p' gattaca.txt

sed '1~2d' gattaca.txt

One can add new material to a file in such a manner with the insert option:

sed '1,2 i\foo' file or sed '1,2i foo' file

Multiple Commands

Multiple commands in sed can be applied with the -e option or with semi-colon separation between commands.

The following selectively prints lines 1,2 and 5,6.

sed -n '1,2p; 5,6p' file or sed -n -e '1,2p' -e '5,6p' file

Backrefences

Like the ampersand metacharacter, a backreference defines a region in a search and then allows that region to be backreferenced. A statement with a backreference is actually beyond being a regular language.

Regions are established by parentheses and then referenced by \1, \2 etc. For example;

sed -E 's/([A-Z]*)([A-Z]*)([A-Z]*)/First Column \1 Second Column \2 Third Column \3/' gattaca.txt

Parallel sed

Parallel sed is particularly helpful if one has a very large file that requires a regular expression edit. A simple example would be to remove dollar signs from file, which would normally be carried out with sed 's/$//g' filename. Like with grep, making use of the GNU parallel suite can improve speed.

sinteractive -n8 module purge module load foss/2019b module load parallel/20190922 parallel -j200% --pipe --block 2M LC_ALL=C --pipe sed 's/$//g' < bigfile

As a data driven programming language AWK is particularly good at understanding and manipulating text structured by fields - such as tables of rows and columns. Unlike grep, which searches for strings from an input, or sed, which carries out editing on the same, AWK offers more computational options. The organisation of an AWK program follows the form: pattern { action }. This is sometimes structured with BEGIN and END which specify actions to be taken before any lines are read, and after the last line is read.

There are many variants of AWK, but the most common is GNU AWK (often called 'GAWK'). This resource is written with GNU AWK assumed. To check that you have this, run the version command.

awk --version

Internal Field Separator

The easiest and certainly one of the most common uses of AWK is create reports from structured data.

Columns and rows are referenced by number (e.g., print $1 for the first column, NR>1 for all rows greater than 1) and by default the space acts as the delimiter. To modify this use awk -F, (or awk -F ',') to use, for example, the comma as the delimiter. Other shell commands can be included in awk.

By default AWK uses a space as the internal field separator. To use a comma invoke with -F e.g. awk -F"," '{print $3}' quakes.csv

Adding new separators to the standard output print of multiple fields is recommended - otherwise AWK will print without any separators. For example;

awk -F"," '{print $1 " : " $3}' quakes.csv

awk -F"," '{print $1 "\t" $3}' quakes.csv

Other shell commands can be piped through AWK

awk -F"," '{print $1 " : " $3 | "sort"}' quakes.csv | less

Selecting Content

A matched pattern in a line can be printed:

awk '/ATVK/ {print $0}' gattaca.txt

awk '/ATVK/ {print $2}' gattaca.txt

The usual metacharacters can be used.

awk '/^ATVK/' gattaca.txt

awk '/QLQA$/' gattaca.txt

The inbuilt length command can be used to print lines of a particular length. Note the double equals syntax.

awk 'length($0) == 28' gattaca.txt

awk '{ if (((length($1) == 10 ) && length($2) == 10) && (length($3) == 10 || length($3) == 5)) && length($4) == 10)) && length($5) == 10)) print }' gattaca.txt

Whereas row numbers are specified by $num, 'NR' specifies the row number. More examples:

awk -F"," 'END {print NR}' quakes.csv

awk -F"," 'NR>1{print $3 "," $2 "," $1}' quakes.csv

awk -F"," '(NR <2) || (NR!=6) && (NR<9)' quakes.csv > selection.txt

Inserting Text

The printf can add text to a file.

awk 'BEGIN{printf "The nucleotide data is in the second line following, the sixth line, etc.\n"}{print}' test-high-gc-1.fastq | less

References

A collection of AWK one-liners are at: http://www.pement.org/awk/awk1line.txt. The file test-high-gc-1.fastq is from Washington State University, Data Progamming Course.

POSIX has three sets of RegEx standards, BRE (Basic Regular Expressions), ERE (Extended Regular Expressions) and SRE (Simple Regular Expressions). SRE is deprecated. Basic Regular Expressions (BRE) are the earliest POSIX standard. The grep command uses these by default.

The Free Software Foundation (FSF) through the GNU utilities extended the basic regular expressions to give additional characters special meaning (i.e., more metacharacters). GNU built on the POSIX tools so that BREs will provide ERE functionality when a backslash is invoked, whereas EREs require the backslash to suppress the metacharacter functionality.

With BRE the following metacharacters must be preceeded by an escape \ to enable their special meaning. ? + { } | ( )

ERE adds the '?', '+', and '|' metacharacters, and it removes the need to escape the metacharacters '(' ')' and '{' '}', which is required in BRE. ERE can be invoked with grep -E and sed -r or sed -E.

For an illustration, try the following, using grep's BRE.

grep '^Geoff|^Jeff' /usr/share/dict/words

Now escape the characters and alternation will apply.

grep '^Geoff\|^Jeff' /usr/share/dict/words

Or use extended regular expressions with grep.

grep -E '^Geoff|^Jeff' /usr/share/dict/words

Parentheses are used to group a character set.

grep '(^Geoff|^Jeff)(rey$|ery$)' /usr/share/dict/words

grep -E '(^Geoff|^Jeff)(rey$|ery$)' /usr/share/dict/words

The question mark makes the preceding character optional in the regex.

grep -w '^colou?r' /usr/share/dict/words grep -wE '^colou?r' /usr/share/dict/words

The '*' and '?' are well-known metacharacters for 'any' (including none) or 'one optional' character respectively. In regex the character '+' represents 'one or more', a non-greedy metacharacter. Note that the '?' metacharacter has a different meaning in regular expressions to the shell metacharacter '?'.

For example:

Search for all files in a directory that start with a website URL

grep -Ei '^https?' * | less

A search in gattaca.txt using BRE and ERE.

grep 'KK\+' gattaca.txt

grep -E 'KK+' gattaca.txt

BRE, ERE, and sed

The sed utility supports most basic regular expressions. In addition the \n sequence in a regular expression matches the newline character and \t for tabs.

To invoke extended regular expressions there is an undocumented feature in sed for Linux which uses -E, -r, or --regexp-extended with the command.

Consider the results of the following:

sed 's/QQLQ?//' gattaca.txt

and compare to

sed -E 's/QQLQ?//' gattaca.txt

Backreferences

Regular expressions can also backreference (which is technically beyond being a regular language), that is match a previous sub-expression with the values \1, \2, etc. The following is a useful example where one can search for any word (case-insensitive, line-numbered) and see if that word is repeated, catching common typing errors such as 'The the'. Note the multiple ways of doing this.

grep -inw '([a-z]+) +\1' file

grep -Einw '([a-z]+) +\1' file

grep -Ein '<([a-z]+) +\1>' file

Another similar example, matching repeat characters rather than words (hencem no -w).

grep '([A-Z])\1' gattaca.txt

An example to append the string "EXTRA TEXT" to each line.

sed -e 's/(.*)/\1EXTRA TEXT/'

AWK

As a data driven programming language awk is particularly good at understanding and manipulating text structured by fields - such as tables of rows and columns.

The organisation of an AWK program follows the form: pattern { action }. This can be structured with BEGIN and END which specify actions to be taken before any lines are read, and after the last line is read. i.e.,

BEGIN {awk commands} /pattern/ {awk commands} END {awk commands}

A collection of awk one-liners are at: http://www.pement.org/awk/awk1line.txt.

The file test-high-gc-1.fastq is from Washington State University, Data Progamming Course.

There are many variants of awk, but the most common is GNU awk (often called 'gawk'). This resource is written with GNU awk assumed. To check that you have this, run the version command.

awk --version

The awk programming language and ERE

Contemporary implementations of awk language uses the ERE engine to process regular expression patterns.

Note there are slight variations in different implementations of the awk programming language which can have significant effects.

For example, if an escape character precedes a character that is not a regular expression, most version of awk will ignore it. Others however, will treate the backslash as a little character and include it.

For example:

awk '/QL\QA$/' gattaca.txt will be treated like awk '/QLQA$/' gattaca.txt in most contemporary versions of awk. Some however will treat awk '/QL\QA$/' gattaca.txt and awk '/QL\\QA$/' gattaca.txt as equivalent.

A regular expression is limited by a finite number of internal states and termination states. A lot of code (e.g., html), scripts, or programming languages, that can nest arbitrarily deep, and the expression will need to have a means to recall the previous elements that it has opened (in html, for example).

This said, arbitrary elements can be parsed with a regular expression. It requires several steps and will probably require some hand-editing. Works OK for small-scale changes! e.g., http://levlafayette.com/node/128

READ: http://htmlparsing.com/regexes.html

Consider using a language-approriate parser instead (e.g., HTML Tidy, lex/yacc/bison, ANTLR etc)

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/UoM-ResPlat-DevOps/SpartanRegEx/master/Images/regexhtml.png

Shell scipts allow for automation of commands, which provides a great deal of power to the user. A simple script is a text file that invokes a shell (such as bash) and runs the commands listed. However, scripts can also make use of shell-assigned variablles, loops, conditional branching, functions and more. When combining shell scripting with regular expressions the user must be aware that the shell environment has its own metacharacters which differ from the regular expression metacharacters. Further, because all HPC job submissions are shell scripts with additional directives to the scheduler, one can mix HPC jobs with shell scripts with regular expression scripts and command.

Using the example of parallel sed, consider the file "bigfile". It is probably unusual that a file has such a name, but that can be used as a variable for a real file name. The following example creates eight files as a job array

#!/bin/bash #SBATCH --job-name="file-array" #SBATCH --ntasks=2 #SBATCH --time=0-00:15:00 #SBATCH --array=1-5

shuf -n 10000 /usr/share/dict/words | fmt -w 72 > random${SLURM_ARRAY_TASK_ID}.txt

module purge module load foss/2019b module load parallel/20190922

parallel -j200% --pipe --block 2M LC_ALL=C --pipe 'sed -i -f changes.sed random${SLURM_ARRAY_TASK_ID}.txt'

The last command is a sed invoking a sed script. A sed script is simply as series of sed commands a stand-alone file. e.g.,

gat ta ca

$ cat changes.sed s/GA/$1/gI s/TA/$2/gI s/CA/$3/gI

The same sed script could be expressed as shell script as well. Note that the sed command content is quoted in the shell script to ensure what is included is not interpreted by the shell.

$ cat changes.sh #!/bin/bash sed -i ' s/GA/$1/gI s/TA/$2/gI s/CA/$3/gI ' "$@"

If the order that these changes were made, the job could be run as a loop or with job dependencies. For example

for item in ./*.txt ; do parallel -j200% --pipe --block 2M LC_ALL=C 'sed -i -f changes.sed random{1..5}.txt'; done

-- Slide --

- Perl is largely derived from

sed,awk, but also with additional programming functions. - Perl RegEx has additional functionality includes lazy matching, backtracking, named capture groups, and recursive patterns. Similar syntax used in Javascript, Python, Ruby, XML Schema.

- Elaboration and examples in

/usr/local/common/RegEx/perl.md,metaperl.pl,radio.pl-- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- Groups allow for match against a previously established match. Lookarounds apply a condition to matches.

- When there is a successful match, Perl provides the variables $1, $2, etc to hold the text matched by their their parenthesis subexpressions. See input variables in

names.plandtempconv.pl - Note that the variables are not assigned if they do not match, and they do not clear! -- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- Perl Compatible Regular Expressions (PCRE). Library written in C (1997), considered more powerful and flexible than POSIX. Incorporated into scripting languages like R and PHP.

- Not the default in Perl! From Perl 5.10, PCRE is available as a replacement for Perl's default regular expression engine.

- Functionality includes Just-in-time compiler support, flexible memory management, consistent escaping rules, extended character classes, minimal matching, unicode character support, etc. -- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- PHP has two types of regular expressions; POSIX-extended, and Perl-compatible. The Perl-compatible regexes must be enclosed in delimiters, but are more powerful.

- There is also a number of string functions which can mimic basic sed functions.

- POSIX-extended have been deprecated from PHP5.3+ and removed from 7.0+

- Examples in

/usr/local/common/RegEx/php.md,posix.php, andpcre.php. -- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- Python has a built-in package called re, which can be imported to perform regular expressions.

- The re package has a typical range of metacharacters, a number of special sequences, special issues with backslashes, and a range of regular expression methods.

- Examples in

/usr/local/common/RegEx/python.md-- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- Java uses the java.util.regex package for regular expressions and has a similar syntax to what is used in Perl.

- Examples in

/usr/local/common/RegEx/java.md-- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- RegEx in all languages tends to be terse and hard to read. The Simple Regex Language (SRL) replaces the complex metacharacters with high-level language constructs.

- Simple RegEx will help you understand complex regular expressions!

- See

simpleregex.md-- Slide End --

-- Slide --

"If you have a problem and you think awk(1) [insert any regex] is the solution, then you have two problems."

-- David Tibrook (1989 Usenix Software Management Workshop, Under 10 Flags (not always smooth sailing)) (see: http://regex.info/blog/2006-09-15/247)

- Keep your regexes simple, unless you really need something complex. Three readable and simple steps are better than one obsfucated and complex step. -- Slide End --

-- Slide --

- XKCD cartoon from Randall Munroe, https://xkcd.com

- Set reference of Chomsky grammer by J. Finkelstein on Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Dale Dougherty, Arnold Robbins, sed & awk (second edition), O'Reilly, 2000 FP 1997

- Jeffrey E. F. Friedl, Mastering Regular Expressions (third edition), O'Reilly, 2006 FP 1997

- Jan Goyvaerts, Regular Expression: The Complete Tutorial, 2007, FP 2006 -- Slide End --

Having multiple processes process the same file is hugely suboptimal anyway; just generate a single sed script and then run it once. Or if you really want to parallelize, split the input file into smaller pieces, run the generated sed script on each in parallel, and then concatenate them back when you are done.

Parallel processing helps when your task is CPU bound, but this one is I/O bound; you are simply creating congestion by having several processes fight over the access to bytes from the disk, and then in this case also fighting over write access back to the same file.

Operations with integers:

width = 20 height = 5*9 width * height 900

Complex numbers:

a=1.5+0.5j a.real 1.5 a.imag 0.5 abs(a)

5.0 f f

Strings manipulation:

word = 'Help' + 'A' word 'HelpA' word[4] 'A' word[0:2] 'He' word[-1]

'A' f f

Defining lists:

a = ['spam', 'eggs', 100, 1234] a[0] 'spam' a[3] 1234 a[-2] 100 a[1:-1] ['eggs', 100] len(a) 4

The while loop:

while b < 10: ... print b ... a, b = b, a+b ... 1 1 2 3 5 8

The if command: First we use the input() statement to insert an integer:

x = int(input("Please enter an integer here: ")) Please enter an integer here: Then we implement the if condition on the number inserted: if x < 0: ... print ('the number is negative') ...elif x == 0: ... print ('the number is zero') ...elif x == 1: ... print ('the number is one') ...else: ... print ('More') ...

The for loop:

... a = ['cat', 'window', 'defenestrate']

for x in a: ... print (x, len(x)) ... cat 3 window 6 defenestrate 12

Defining functions:

def fib(n):

... """Print a Fibonacci series up to n.""" ... a, b = 0, 1 ... while b < n: ... print (b), ... a, b = b, a+b ...

... fib(2000) 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377 610 987 1597

Importing modules:

import math math.sin(1) 0.8414709848078965 from math import * log(1) 0.0

Defining classes:

class Complex: ... def init(self, realpart, imagpart): ... self.r = realpart ... self.i = imagpart ... x = Complex(3.0, -4.5) x.r, x.i (3.0, -4.5)

J. Finkelstein, "Set Inclusions Described by the Chomsky Hiearchy", 2010

Jeffrey E. F. Friedl, Mastering Regular Expressions (third edition), O’Reilly Media, 2007 FP 1997