Precise control of inter-packet gaps is an important feature for reproducible tests. Bad rate control, e.g., generation of undesired micro-bursts, can affect the behavior of a device under test [1]. However, software packet generators are usually bad at controlling the inter-packet gaps [1, 2].

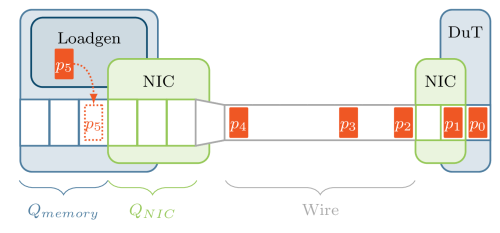

The following diagram illustrates how a typical software packet generator tries to control the packet rate.

It simply tries to wait for a specified time after sending a packet. Network APIs often abstract NICs in a way that indicates that the API pushes a packet to the NIC, so this technique might seem reasonable. However, NICs do not work that way. Sending a packet to the API merely places it in a queue in the main memory. It is now up to the NIC (which may or may not be notified by the API about the new packet immediately) to fetch and transmit the packet asynchronously at a convenient time.

This means that trying to push packets to a NIC is futile. This is especially important at rates above 1 Gbit/s where nanosecond-level precision is required (length of a minimal sized packet at 10 Gbit/s: 67.2 nanoseconds). Sending a single packet requires at least two round trips across the PCIe bus: One to notify the NIC about the updated queue, one for the NIC to fetch the packet. Each PCIe operation introduces latencies and jitter in the nanosecond-range.

Another problem with this approach is that the queues, and therefore batch processing, cannot be used. However, batch processing is an important technique to achieve line rate at high packet rates.

MoonGen therefore implements two ways to prevent this problem.

Intel 10 and 40 GbE NICs (ixgbe and i40e) support rate control in hardware. This can be used to generate CBR or bursty traffic with precise inter-departure times.

Our paper features a detailed evaluation of this feature and compares it to software methods.

The hardware supports only CBR traffic. Other traffic patterns, especially a Poisson process, are desirable.

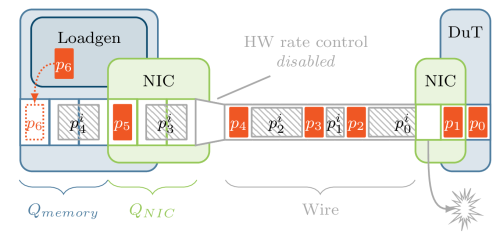

The problem that software rate control faces is that it needs to generate an 'empty space' on the wire. We circumvent this problem by sending bad packets in the space between packets instead of trying to send nothing. The following diagram illustrates this concept.

A bad packet is a packet that is not accepted by the DuT (device under test) and filtered in hardware before it reaches the software. These packets are shaded in the figure above. We currently use packets with an invalid CRC and an invalid length if necessary. All common NICs drop such packets immediately in hardware as further processing of a corrupted packet is pointless. This does not affect the running software. Our paper contains a measurement which shows that this is the case.

If the DuT's NIC does not do this or if a hardware device is to be tested, then a switch can be used to remove these packets from the stream to generate 'real' space on the wire. The effects of the switch on the packet spacing needs to be analyzed carefully, e.g., with MoonGen's inter-arrival.lua example script.

[1] Paul Emmerich, Sebastian Gallenmüller, Gianni Antichi, Andrew W. Moore, and Georg Carle. "Mind the Gap – A Comparison of Software Packet Generators" In ACM/IEEE Symposium on Architectures for Networking and Communications Systems (ANCS 2017), Beijing, China, May 2017. [2] Alessio Botta, Alberto Dainotti, and Antonio Pescapé. "Do you trust your software-based traffic generator?" In IEEE Communications Magazine, 48(9):158–165, 2010.