-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 13

/

05-Categorical_variables.Rmd

201 lines (119 loc) · 14.2 KB

/

05-Categorical_variables.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

---

title: "Categorical Variables"

author: "Jon Lefcheck"

date: "January 16, 2021"

output: html_document

---

# Categorical Variables

While SEM was initially derived to consider only continuous variables (and indeed most applications still do), it's often the case--especially in ecology--that the observed variables are discrete. For example: binary (yes/no, failure/success, etc.), nominal (site 1, site 2), or ordinal levels (small < medium < large). Newer advances in modeling allow for the incorporation, either directly or in a more roundabout fashion, of categorical variables into SEM.

There are two way that categorical variables could be included: as exogenous (predictors) or endogenous (responses). We will deal with the simpler case of exogenous categorical variables first, as they pose not so much of a computational issue but a conceptual one.

## Introduction to Exogenous Categorical Variables

Recall that a linear regression predicting y has the following standard form:

$$y = \alpha + \beta_{1}*x_{1} + \epsilon$$

where $\alpha$ is the intercept, $\beta_{1}$ is the slope of the effect of $x$ on y, and $\epsilon$ is the residual error.

When $x$ is continuous, the intercept $\alpha$ is intepreted as the value of y when $x$ = 0. All good.

For categorical factors, the intercept $\alpha$ has a different interpretation. Consider a value of $x$ with $k$ levels. Since the levels of $x$ are discrete and presumably can never assume a value of 0, $\alpha$ is instead the mean value of y at the 'reference' level of $x$. (In R, the reference level is the first level alphabetically, although this can be reset manually.) The regression coefficients $\beta_{k}$ are therefore the effect of each other level *relative* to the reference level. So for $k$ levels, there are $k - 1$ coefficients estimated with the additional $\alpha$ term reflecting the $k$th level.

Another way to think about this phenomenon is using so-called 'dummy' variables. Imagine each level was broken into a separate variable with a value of 0 or 1: a two-level factor with levels "a" and "b" would then become two factors "a" and "b" each with the levels 0 or 1. (In R, this would mean transposing rows as columns.)

Now imagine setting all the values of these dummy variables to 0 to estimate the intercept: this would imply the total absence of the factor, which is not a state. Another way of thinking about this is that the dummy variables are linearly dependent: if "a = 1" then by definition "b = 0" as the response variable cannot occupy the two states simultaneously. Hence the need to set one level as the reference, so that the effect of "a" can be interpreted relative to the absence of "b", and also why you don't recover as many coefficients as there are levels. I once heard it state that one level had to "fall on the sword" so that we can estimate the other levels.

This behavior presents a challenge for parameterizing path diagrams: there is not a single coefficient for the path from $x$ -> $y$, nor are there enough coefficients to populate a separate arrow for each level of $x$ (because one level must serve as the reference).

There are a few potential solutions:

* for binary variables, set the values as 0 or 1 and model as numeric, which would yield a single coefficient representing the expected change in $y$ as $x$ changes from state "0" to the other state "1."

* for ordinal variables, set the values depending on the order of the factor, e.g., small = 1 < medium = 2 < large = 3, and then model as numeric, which would also yield a single coefficient represented the expected change in $x$ as you climb the ordinal ladder from smallest, to medium, and so on.

* create dummy variables for each level: this is procedurally the same as above (splitting levels into $k$ - 1 separate variables that have a state of or/1). The key here is not to create $k$ variables, to avoid the issue raised above about dependence among levels. This is the default behavior of *lavaan*.

This approach becomes prohibitive with large number of categories or levels and can greatly increase model complexity. Moreover, each level is treated as an independent variable in the tests of directed separation, and thus will inflate the degrees of freedom in a piecewise application.

* for suspected interactions with categorical variables, a multigroup analysis is required. In this case, the same model is fit for each level of the factor, with potentially different coefficients (see the following chapter on Multigroup Modeling).

* test for the effect of the categorical variable using ANOVA, but do not report a coefficient. This approach would indicate whether a factor is important (i.e., whether the levels significantly differ with respect to the response), but omits important information about which levels and the direction and magnitude of change. For example, does a significant treatment effect imply an increase or decrease in the response, and by how much? For this reason, such an approach is valid but not ideal.

A alternate approach draws on this final point and involves testing and reporting the model-estimated or marginal means.

## Exogenous Categorical Variables as Marginal Means

All models can be used for prediction. In multiple regression, the predicted values of one variable are often computed while holding the values of other variables at their mean. Marginal means are the averages of these predictions. In other words, they are the expected average value of one predictor given the other co-variables in the model.

For categorical variables, marginal means are particularly useful because they provide an estimated mean for each level of each factor.

Consider a simple example with a single response and two groups "a" and "b":

```{r}

set.seed(111)

dat <- data.frame(y = runif(100), group = letters[1:2])

model <- lm(y ~ group, dat)

summary(model)

```

Note that the summary output gives a simple coefficient, which is the effect of group "b" on y in the absence of group "a". As we established above, the intercept is simply the average of y in group "a":

```{r}

summary(model)$coefficients[1, 1]

mean(subset(dat, group == "a")$y)

```

The marginal means are the expected average value of y in group "a" AND group "b".

```{r}

predict(model, data.frame(group = "a"))

predict(model, data.frame(group = "b"))

```

Because this is a simple linear regression, these values are simply the means of the two subsets of the data, because they are not controlling for any other covariates:

```{r}

mean(subset(dat, group == "a")$y)

mean(subset(dat, group == "b")$y)

```

Let's see what happens we add a continuous covariate:

```{r}

dat$x <- runif(100)

model <- update(model, . ~ . + x)

```

Here, the marginal mean must be evaluated while holding the covariate $x$ at its mean value:

```{r}

predict(model, data.frame(group = "a", x = mean(dat$x)))

mean(subset(dat, group == "a")$y)

```

You'll note that this value is now different than the mean of the subset of the data because, again, it controls for the effect of $x$ on $y$.

This procedure gets increasingly complicated with both the number of factor levels and the number of covariates. The *emmeans* package provides an easy way to compute marginal means:

```{r, message = FALSE, warning = FALSE}

library(emmeans)

emmeans(model, specs = "group") # where specs is the variable or list of variables whose means are to be estimated

```

You'll note that the output value for group "a" gives the same as using the `predict` function above, but also returns the marginal mean for group "b" while also controlling for $x$:

```{r}

predict(model, data.frame(group = "b", x = mean(dat$x)))

```

and so is a handy wrapper for complex models.

The `emmeans` function goes onto to provide lower and upper confidence intervals, which provides an additional level of information, namely whether each mean differs significantly from zero. Coupled with ANOVA test for differences among categories, the marginal means provide key information that is otherwise lacking, namely whether and *how* the response value changes based on the factor level. It is import

The *emmeans* package provides additional functionality by conducting post-hoc tests of differences among the means of each factor level:

```{r}

emmeans(model, list(pairwise ~ group))

```

You'll note a second output which is the pairwise contrast between the means of groups "a" and "b" with an associated significance test.

These pairwise Tukey tests provide the final level of information, which is whether the response in each level varies significantly from the other levels.

To adapt this to SEM, the `coefs` function in *piecewiseSEM* adopts a two-tiered approach by first computing the significance of the categorical variable using ANOVA, and then reports the marginal means and post-hoc tests:

```{r, message = FALSE, warning = FALSE}

library(piecewiseSEM)

coefs(model)

```

In this output, we retrieve the normal output for the continuous $x$ including a standardized effect size. The significance test from the ANOVA is reported in the row corresponding to the group effect, and below that are the marginal means for each level of the grouping factor. Note that there are no standardized estimates for either the ANOVA effect or the marginal means, because as we have established, these are not linear coefficients and therefore cannot be standardized as usual.

This solution provides a measure of whether the path between the exogenous categorical variable and the response is significant as well as parameters for each level in the form of the model-estimated marginal means.

## Exogenous Categorical Variables as Marginal Means: A Worked Example

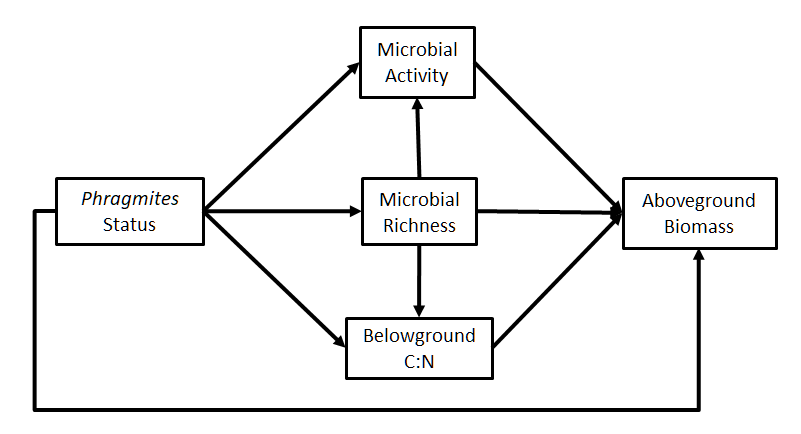

Let's consider an example from Bowen et al. (2017). In this study, the authors were interested in how different microbiomes of the salt marsh plant *Phragmites australis* drive ecosystem functioning, and ultimately the production of aboveground biomass. In this case, they considered three microbial communities: those from a native North American lineage, from Gulf Coast lineage, and an introduced lineage. There were additional genotypes within each community type, necessitating the application of random effects to account for intraspecific variation.

We will fit a simplified version of their full path diagram, focusing only on aboveground biomass (although they test the effect on belowground biomass in their study as well).

In this case, the variable "*Phragmites* status" corresponds to the three community types and can't be represented using a single coefficient. Thus, the marginal-means approach is ideal to elucidate the effect of each community type on both proximate and ultimate ecosystem properties while testing the overall significance of this path.

Let's read in the data and construct the model:

```{r, message = FALSE, warning = FALSE}

bowen <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jslefche/sem_book/master/data/bowen.csv")

bowen <- na.omit(bowen)

library(nlme)

bowen_sem <- psem(

lme(observed_otus ~ status, random = ~1|Genotype, data = bowen, method = "ML"),

lme(RNA.DNA ~ status + observed_otus, random = ~1|Genotype, data = bowen, method = "ML"),

lme(below.C ~ observed_otus + status, random = ~1|Genotype, data = bowen, method = "ML"),

lme(abovebiomass_g ~ RNA.DNA + observed_otus + belowCN + status, random = ~1|Genotype, data = bowen, method = "ML"),

data = bowen

)

```

And let's retrieve the output:

```{r}

summary(bowen_sem, .progressBar = FALSE)

```

In this case, it appears that the model fits the data well enough based on the Fisher's *C* statistic (*P* = 0.057), which is what the original authors used. Note that the likelihood-based $\chi^2$ statistic actually implies poor fit (*P* = 0.043). In this case, examining the d-sep tests suggests the inclusion of the path from $belowCN$ to $below.C$ might improve the fit. However, we are applying a tool that was not available to the original authors, so we will proceed as they did and assume adequate fit.

The linkage between microbial community type ($status$) and richness ($observed_otus$) is non-significant, but the other paths are significant. Examination of the marginal means indicates microbial activity ($RNA.DNA$) and belowground carbon ($below.C$) are generally highest in *Phragmites* with native microbial communities based on the post-hoc tests. However, none of these properties appear to influence the ultimate production of biomass ($abovebiomass_g$). Rather, that property appears to be entirely controlled by the plant microbiome type ($status$): those with the introduced microbial community have significantly higher aboveground biomass based on their marginal mean after controlling for microbial activity and soil nutrients.

Thus, despite a multi-level categorical predictor ($status$), the two-step procedure of ANOVA and calculation of marginal means allows for a more mechanistic understanding of the drivers of plant biomass in this species.

## Endogenous Categorical Variables

Endogenous categorical variables are far trickier, and at the moment, are not implemented in *piecewiseSEM*.

In the case of endogenous categorical variables in a piecewise framework, there are really only two solutions:

* for binary variables, set the values as 0 or 1 and model as numeric, which would yield a single coefficient.

* for ordinal variables, set the values depending on the order of the factor, e.g., small = 1 < medium = 2 < large = 3, and then model as numeric, which would yield a single coefficient.

Nominal variables (i.e., levels are not ordered) could be modeled using multinomial regression, although this method would have to be executed by hand. An alternative is to use the factor levels to construct a *composite variable*, the subject of a later chapter. *lavaan* provides a robust alternative in the form of confirmatory factor analysis (see [http://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/cat.html](http://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/cat.html)). In *piecewiseSEM*, composites must be constructed by hand, although this procedure is not hugely prohibitive.

## References

Bowen, J. L., Kearns, P. J., Byrnes, J. E., Wigginton, S., Allen, W. J., Greenwood, M., ... & Meyerson, L. A. (2017). Lineage overwhelms environmental conditions in determining rhizosphere bacterial community structure in a cosmopolitan invasive plant. Nature communications, 8(1), 433.