-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 2

/

Copy pathgithub.qmd

180 lines (102 loc) · 11.1 KB

/

github.qmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

---

title: "Git and GitHub"

---

At R For The Rest Of Us, we collaborate on projects using Git and GitHub. Git is the gold standard for version control, and using it in conjunction with GitHub provides a neat way of exploring the more advanced Git features within a friendly interface. This section covers the basics of the Git etiquette we adopt, as well as a few how-tos and worked examples.

## Overview

- Each project has its own unique repository

- The central repository for each project lives on GitHub; this is also referred to as `origin`

- Everyone working on that project is invited to the GitHub repo, and we then `clone` the repo to our own computers (this gives us what we call local repos)

The rest of this section assumes a basic understanding of how Git works. The main thing to note for new users is that, unlike something like Dropbox, changes only make it to the central repo (and from there to others), if Git is explicitly told about them via `add`, `commit` and `push` commands.

### Setting Up a New Repo

The easiest way to create a new repo is to do it on GitHub. Make sure to give it a name that clearly identifies the project!

Then follow the instructions that come up once you've clicked on Create Repository. Pick the option that best corresponds to the stage you have reached. If you have already used `git init` to make your local folder into a Git repo, pick the second option. If not, pick the first.

When creating a new repo, we want to add three files: `README.md` (which is added automatically in the first option), `.gitignore` and `.gitattributes`. The default branch of a new repo should be called `main`. This is GitHub's new default, so should happen automatically.

#### README.md

This file should contain information about the purpose of the repo, and any information useful to other team members interacting with it. We sometimes make our repos available to clients towards the end of projects, so keep the contents of the `README` accessible to non-R specialists.

#### .gitignore

The best way to do this is by using `{usethis}` within `R`. Navigate to your repo, and type:

```{r}

#| echo: true

usethis::git_vaccinate()

```

This will add a .gitignore file that excludes files with the following extensions from being tracked by Git.

```

.Rproj.user

.Rhistory

.Rdata

.httr-oauth

.DS_Store

```

#### .gitattributes

This file allows us to work across different Operating Systems, which have different behaviours for handling line endings. Create a text file and rename it to `.gitattributes` (note, not `gitattributes.txt`) and copy the following content into it:

```

# Let Git's auto-detection algorithm infer if a file is text. If it is,

# enforce LF line endings regardless of OS or git configurations.

* text=auto eol=lf

# Isolate binary files in case the auto-detection algorithm fails and

# marks them as text files (which could break them).

*.{png,jpg,jpeg,gif,webp,woff,woff2} binary

```

### Cloning an Existing Repo

To clone a repo from GitHub, it either needs to be public, or you need to have been invited to the repo. We invite all team members to the `sandbox` repo we created, and use it as a way of exploring different Git tricks.

To clone the repo, go to [its GitHub page](https://github.com/rfortherestofus/sandbox) and click on Code, copy the text provided by GitHub by clicking on the copy icon.

Next, create a new folder called `sandbox` somewhere on your computer. Navigate to that folder in your terminal, and type `git clone`

then paste in the text you've just copied, type space then ` .` and hit `Enter`. That full stop means "clone the folder into the directory where I am currently". If you miss that out, you'll end up with this git folder called `sandbox` inside your `sandbox` folder which will make things very confusing. Your command should look like this:

```

git clone https://github.com/rfortherestofus/sandbox.git .

```

This will create a local copy of the repo on your computer.

Depending on how your computer is set up, you may see a folder called `.git`. This is a hidden folder. Do not edit its contents!

## Git Etiquette

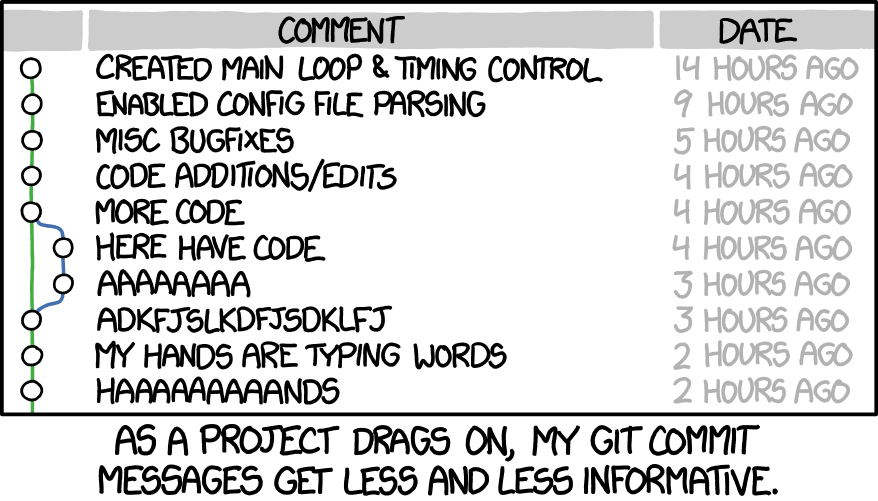

### Commit messages

There is an art to writing good commit messages.

Some organisations have very strict guidelines on that. Here, we just try to follow the following rules:

- Commit often and frequently; this allow you to easily backtrack to the point where your code was doing what it should be.

- Write clear commit messages. Things like "I fixed it!" are not all that helpful when trying to find a commit that addressed a specific problem!

- If the change you're making is linked to an issue on GitHub (we'll come to issues later), include the number of the issue in the commit message (e.g. "Added section on commit messages - #4"). GitHub picks this up and adds a message into the issue, which allows us to easily keep track of progress.

### Using branches

We encourage the use of branches when collaborating on projects. These can be daunting to new Git users, but once we get the hang of them, there's no looking back!

#### What are branches?

We mentioned the default branch, `main` earlier. Think of this as the "stable universe" as far as the project is concerned. It contains up-to-date code that others can reliably use. A branch is essentially an "alternate universe" for the project, where we can experiment, make changes, test new things, all without disrupting the "stable universe" that others rely on.

Some organisations only ever allow changes to be made via a branch. There's lot of wisdom in that, but sometimes it can become cumbersome. Here are some use cases where you could consider working in the `main` branch:

- you are the only person working on the project

- you are adding something to the project that doesn't interact at all with the code others are writing

But even in those cases, you could consider using a new branch to be on the safe side. If in doubt, check with David.

#### Creating a New Branch

Creating a new branch is trivial. As with commit messages, we want to make sure the name of the branch gives a clear indication of its purpose. Say a client wants to add a new timeline to their report. The report is otherwise working as it should be. To work in a branch, and thereby allow them to keep using the report as is while you figure this out, you'll want to

- make sure you're branching off an up-to-date `main`: `git pull`

- create a new branch with a clear name: `git checkout -b adding-timeline-feature`

You can also do this in RStudio or in GitHub Desktop.

Now the files that you see are ones that belong to your alternate universe called "adding timeline feature". Everything will look the same, but changes you add and commit here won't affect anything in `main`; if it all goes horribly wrong, you can delete this branch and know all is still well in the "stable universe". You can then switch between universes as follows:

- Commit (or stash) everything you've done within your branch

- Go back to the "stable universe": `git checkout main`, probably followed by `git pull` to see what's happened there in your absence. The modifications you've made within `adding-timeline-feature` will no longer be visible to you.

- Go back to your own alternate universe: `git checkout adding-timeline-feature`, and your modifications are back!

While you're working on your feature, you can keep your branch backed up on GitHub, safe in the knowledge that it doesn't affect anything in `main`. The first time you push, you need to "set the upstream".

```

git push -u origin adding-timeline-feature

```

Every time after that, you can just use `git push`. Pushing your branch to `origin` allows others to view your branch (useful if you want to get feedback along the process), and ensures that if something bad happens to your computer, your work is stored somewhere else.

Give it a go in our `sandbox` repo.

Create a new branch, with a name of your choosing, and add a quote to `quotes/client-quotes.txt`. Add, commit and push (remember to set the upstream branch!). Then checkout main again, and open the `client-quotes.txt` file. The quote you've added should no longer be there. Switch back to your branch, and it will reappear. The GitHub page for this repo should also now include your branch in the list of branches.

#### Creating a Pull Request

Pull request are the way we merge the work you've done in a branch back into our "stable universe" while allowing someone else to review the changes in the process.

TODO: example create a pull request for the added quote

TODO: best for the branch author / person who made the most recent contribution to it to initiate the pull request

TODO: get up to speed with `main` first.

#### Reviewing a Pull Request

TODO: We haven't really done this, but it might be worth thinking about if projects get bigger - you can set things so that a merge into `main` needs to be approved by someone other than the person creating the pull request; a useful way to keep things safe, but we need to all be happy with pull requests first

#### Merging etiquette and branch hygiene

At this point comes a policy decision, which can be influenced by workload: who completes the approved merge? It could be the person who did the work, or the person who approved the merge. If there happen to be conflicts (see below), this can be non trivial. GitHub will tell you if there will be a conflict, in which case we can discuss who is best placed to resolve it.

And a second policy decision, which can be influenced by how we want to use the branches: should a branch be deleted once it has been merged in? The advantage of deleting branches as part of the merge is that this avoids needing to tidy them up at a later stage. You might have a feature you're working on where a quick bug fix was needed, but you'd like to keep working on it to improve the code once the immediate need for the bug fix has passed. In that case, it might be best to keep the branch, but we'll need to make sure we keep it up to speed with the "stable universe" by merging `main` into that branch before picking it up again.

To check the status of your branch(es) compared to others, click on the "branches" icon in the repo's GitHub page. Here you can see by how many commits a branch is ahead and behind the default branch (typically `main`). A branch that is "behind" `main` by a large number of commits and hasn't been updated for a while is probably a candidate for deletion, but if it wasn't your branch, check with its author first!

### Dealing with merge conflicts

The best way to deal with conflicts is to avoid causing them in the first place!

TODO: pull across info from my old team doc

TODO: I use TortoiseGit as a merge tool; makes it easier to compare the changes; what do others use?

### Writing good issues

TODO: Decide if we want a section on this