Software has been daunted with memory leaks for a long time. There exists one interesting question to ask, can we make memory management more safe with static code analysis? Can we make a compiler help us with common mistakes made, when dealing with memory management?

- Introduction

- Memory Leaks

- Balanced Storage

- Conclusion

Long runnning applications needs to allocate memory to store objects that lives a long time. Though, during allocation and storing of objects a developer might forget to handle the case when the object is no longer needed, and it needs to be deleted. Even though, the developer remembers to handle the deletion of objects, there still exists blind spots where the reference count of objects does not reach zero and thus creates a memory leak in a garbage collected language or languages that uses reference counting. We will try to cover some of these problems and present a solution to these problems.

A memory leak is objects we intended to delete. But instead of being deleted, they remained on runtime.

We extend an EventEmitter class to create a user model:

class User extends EventEmitter {

private title: string;

public setTitle(title: string) {

this.title = title;

this.emit('change:title', title);

}

}We also define the following view class:

class View {

constructor(private user: User) {

this.user.on('change:title', () => {

this.showAlert();

});

}

public showAlert(title: string) {

alert(title);

}

}Then in some other class's method we instantiate the view with a referenced user model:

class SubView {

constructor(private user: User) {}

public showAndRemoveView() {

this.view = new View(this.user);

this.view = null; // this.user persists.

// A memory leak, `view` cannot be garbage collected.

}

}As you can see we did a mistake. We unreferenced the view. And we expected it to be garbage collected. But instead we caused a memory leak. Did you spot in which line was causing a memory leak? It is on this line:

this.user.on('change:title', () => {

this.showAlert(); // `this` inside the closure is referencing view. So `this.user` is referencing `view`.

});As the comment says, this inside the closure is referencing the view. So this.user is referencing view. Because the reference count haven't reached zero, the garbabge collector cannot garbage collect the view.

We want to prevent memory leaks by static code analysis. But in doing so, we must analyse the source of memory leaks. By definition a memory leak is an unused resource at runtime. We allocate memory and initialize our resource. When the resource is no longer needed we need to deallocate it. In a garbage collected language we can unreference objects so they get garbage collected. And for a manual managed memory programming languages, we must deallocate it manually by writing some sort of expressions. In a majority of cases, if not all, a memory leaked resource often has one or more references to itself. In a garbage collected language this always holds true, they always have at least one reference to itself(otherwise they would be garbage collected).

Let us just annotate these methods that uses these references. I have not shown you the EventEmitter class yet. Lets begin by examine it:

export class EventEmitter {

public eventCallbacks: EventCallbacks = {}

public register(event: string, callback: Callback) {

if (!this.eventCallbacks[event]) {

this.eventCallbacks[event] = [];

}

this.eventCallbacks[event].push(callback);

}

public unregister(event: string, callback: Callback): void {

let callbacks = this.eventCallbacks[event].length;

for (let i = 0;i < callback.length; i++) {

if (this.eventCallbacks[event][i] === callback) {

this.eventCallbacks[event].splice(i, 1);

}

}

}

public emit(event: string, args: any[]) {

if (this.eventCallbacks[event]) {

for (let callback of this.eventCallbacks[event]) {

callback.apply(null, args);

}

}

}

}The property eventCallbacks above is hashmap of a list of callbacks for each event. We register new events with the register method and unregister them with the unregister method. We can emit a new event with the emit method. The property eventCallbacks is a potential leaking resource storage, because it can hold callbacks on events that a developer might forgot to unregister. Though the essentials here, is the register and unregister methods. Because their role is to register and unregister events. This leads us to think, can we somehow require a user who calls register always call unregister? If possible, we would prevent having any memory leaks. Let us answer this question later, and begin with annotating them first.

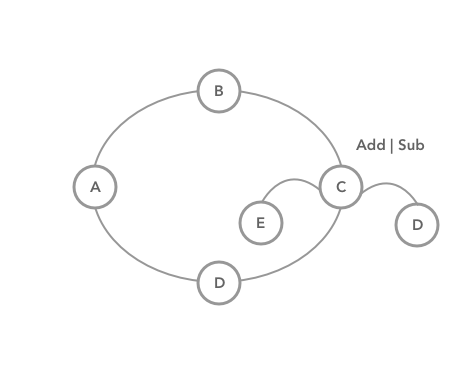

Lets just the add a temporary classification syntax for our methods(we will later present that this classification syntax is not needed):

MethodClassification :: add | sub Name MethodDeclaration

The add and sub keywords are operators that classify methods with a name that identifies that elements are being added or subtracted from our storage when the method is called. So for our User model which is an extension of the EventEmitter class, we can go ahead and classify our methods:

export class User extends EventEmitter {

add UserChangeTitleCallback

public register(event: string, callback: Callback) {

super.register.apply(this, arguments);

}

sub UserChangeTitleCallback

public unregister(event: string, callback: Callback): void {

super.unregister.apply(this, arguments);

}

}Now, every consumer of these two methods will have some additional checks that they need to pass. First, if they are in the same scope they need to call register before unregister. Or in other words an add classified method needs to be called before a sub classified method. And through out this document we would refer an add classified method as an add method. And a sub classified method as a sub method.

class View {

constructor(private user: User) {

this.user.register('change:title', this.showAlert);

this.user.unregister('change:title', this.showAlert);

}

}Though, in this case having the method calls on the same scope is not quite useful. Since we unregister the event directly. It would be as good as not calling anything at all. But in order to pass the compiler checks we can also call a sub method in another declared method of the class.

class View {

private description = 'This is the view of: ';

constructor(private user: User) {

this.user.register('change:title', this.showAlert);

}

public removeUser() {

this.user.unregister('change:title', this.showAlert);

}

public showAlert(title: string) {

alert(this.description + title);

}

}In the above example. We call this.user.unregister('change:title', this.showAlert); in the method removeUser to pass the compiler check. We pass the compiler check because the class's methods is now balanced. There is one add method declaration and one corresponding sub method declaration in the class.

To achieve balance either a scope needs to be balanced or a class's methods need to be balanced. A balanced scope, means that given infinite amount of time, there is a certainty that a sub method being called to match a corresponding add method call. A balanced class, means that there exists a corresponding sub method declaration for an add method declaration.

| Location | Targets | Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Class | Methods | For every add method declaration there must exist a corresponding sub method declaration. |

| Scope | Call expressions | Given infinite amount of time, one added resource will eventually get subtracted. |

Notice first, that whenever there is a scope with unmatched add or sub methods. The unmatched methods classifies the containing method. Here we show the inherited classifications in the comments below:

class View {

private description = 'This is the view of: ';

// add UserChangeTitleCallback

constructor(private user: User) {

this.user.register('change:title', this.showAlert);

}

// sub UserChangeTitleCallback

public removeUser() {

this.user.unregister('change:title', this.showAlert);

}

public showAlert(title: string) {

alert(this.description + title);

}

}The methods in our class is now balanced. When a class is balanced it implicitly infers that the a balance check should be done in an another scope other than in the current class's methods. This could be inside an another class's method that uses the current class's add method.

Now, let use the above class in an another class we call SubView:

class SubView {

private view: View;

public showAndRemoveView() {

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method(constructor).

this.view = null;

}

}The above code does not pass the compiler check, because there is no matching sub method. Also the code causes a memory leak.

We can add the call expression this.view.removeUser() below, to match our add method. Now, on the same scope we have a matching add and sub methods. So the compiler will compile the following code. Also, the code, causes no memory leaks:

class SubView {

private view: View;

public showAndRemoveView() {

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method(constructor).

this.view.removeUser(); // Sub method.

this.view = null;

}

}If we don't add a sub method call above. The containing method will be classified as an add method:

class SubView {

private view: View;

// add UserChangeTitleCallback

public showAndRemoveView() {

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method.

this.view = null;

}

}The method show inherited the add classification from the expression new View(this.user).

We have so far only considered object having an instant death. And this is not so useful. What about objects living longer than an instant? We want to keep the goal whenever an object has a certian death (given infinite amount of time) the compiler check will pass. Now, this leads us to our next rule:

Passing a sub method as an argument to a call expression will balance an add method in current scope.

Lets go ahead and add our call expression, that accepts a corresponding sub method for our add method:

class SubView {

private view: View;

public show() {

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method.

this.onDestroy(this.remove); // Passing a sub method to a call expression matches the add method above.

}

private onDestroy(callback: () => void) {

this.deleteButton.addEventListener(callback);

}

// sub UserChangeTitleCallback

public remove() {

this.view.removeUser(); // Sub method.

this.view = null;

}

}Now, we have ensured a certain death of our view, because the method remove has inherited a sub classification. So this.remove is a callback that corresponds to the add method(constructor) new View(this.user):

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method(constructor).

this.onDestroy(this.remove); // Sub method passed as an argument.this.onDestroy takes a callback. And we passed in a corresponding sub method for our add method above. Which means, we have a possible death for our view. The scope is balanced and the compiler will not complain. Notice, whenever an add method is balanced with a sub method or whenever there is a path, call path, that can be reached, to balance a sub method. The code will pass the compiler check. Because in other words, we have ensured a certain death of our allocated resource.

BIRTH ---> DEATH

BIRTH ---> CALL1 ---> CALL2 ---> CALLN ---> DEATH

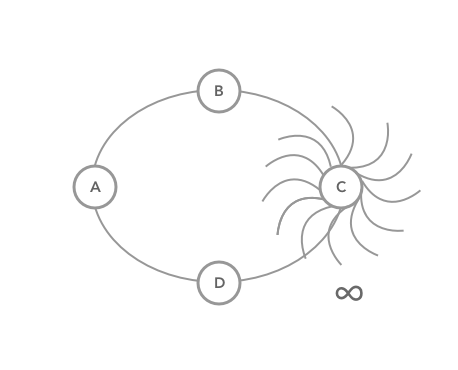

In addition to call paths, we can also create a loop path, to make objects live longer than an instance.

We will use a C++ console application to show what a loop path is. Our console application will give you four choices:

- Add an item.

- Delete an item.

- Show all items.

- Quit application.

Each item is defined as:

struct Item {

string name;

Item(string _name):name(_name) {}

};And our storage as:

class Storage {

public:

vector<Item*> items;

Storage() {}

void addItem(string name) {

items.push_back(new Item {name});

}

void deleteItem(int index) {

auto item = items.begin() + index;

objects.erase(item);

delete *item;

}

};The compiler will statically classify addItem is an add method and deleteItem is a sub method. We will cover the details later.

We have while loop that ask us our options:

while (true) {

cout << "What do you want to do?" << endl;

cout << " (1) Add an item." << endl;

cout << " (2) Delete an item." << endl;

cout << " (3) Print all items." << endl;

cout << " (q) Quit." << endl;

cin >> answer;

...

}And we can choose an option for adding one item:

if (answer == '1') {

string itemName;

while (true) {

cout << "Type the item you want to add:" << endl;

cin >> itemName;

if (cin.fail()) {

clearInput();

cout << "Wrong answer!" << endl;

continue;

}

storage.addItem(itemName);

cout << "Added object: " + itemName << endl;

break;

}

}The compiler will not compile the above code. Since we have not used the sub method storage.deleteItem. Let us define that option too:

else if(answer == '2') {

int index;

cout << "Type the index on the item you want to delete:" << endl;

cin >> index;

storage.deleteItem(index);

}Now, if we consider our while loop, looping infinite of time. Given infinite amount of time, we can derive that what eventually gets added to our storage must eventually be deleted. This is derived by Murphys Law, whatever can happen, will happen. So we have ensured that there is certain death for our added reources.

Here is the whole application source code:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <ctype.h>

using namespace std;

struct Item {

string name;

Item(string _name):name(_name) {}

};

class Storage {

public:

vector<Item*> objects;

Storage(): objects { new Item { "eyeglasses" } } {}

void addItem(string name) {

objects.push_back(new Item {name});

}

void deleteItem(int index) {

auto item = objects.begin() + index;

objects.erase(item);

delete *item;

}

};

void clearInput()

{

cin.clear();

cin.ignore(numeric_limits<streamsize>::max(), '\n');

}

int main ()

{

Storage storage;

char answer;

while (true) {

cout << "What do you want to do?" << endl;

cout << " (1) Add an item." << endl;

cout << " (2) Delete an item." << endl;

cout << " (3) Print all items." << endl;

cout << " (q) Quit." << endl;

cin >> answer;

if (cin.fail()) {

clearInput();

cout << "Wrong answer!" << endl;

continue;

}

if (answer == 'q') {

break;

}

if (!(answer >= '1' && answer <= '3')) {

clearInput();

cout << "Wrong answer!" << endl;

continue;

}

if (answer == '1') {

string itemName;

while (true) {

cout << "Type the item you want to add:" << endl;

cin >> itemName;

if (cin.fail()) {

clearInput();

cout << "Wrong answer!" << endl;

continue;

}

storage.addItem(itemName);

cout << "Added object: " + itemName << endl;

break;

}

}

else if(answer == '2') {

int index;

cout << "Type the index on the item you want to delete:" << endl;

cin >> index;

storage.deleteItem(index);

}

else {

auto objects = storage.objects;

auto storageLength = objects.size();

for (int i = 0; i<storageLength; i++) {

cout << objects[i]->name << endl;

}

}

}

return 0;

}

Notice, for a loop statement. In order for it to reach balance, i.e. whatever gets added will eventually gets deleted, it must loop infinite amount of times(a while loop). And it needs to contain at least one branch for an add method call and one branch for a sub method call. Any branches that contains a break statement needs to delete all objects in the storage. All other branches must continue looping after their execution.

(Our break branch above does not delete all objects in the storage. Though breaking the while-loop will eventually exit the application and therefore delete/deallocate all objects.)

In C++ we initialize with new and deallocate objects with delete. Our balanced storage definition so far have only considered collections as data types. The question is, if we can apply the same balancing rules too prevent memory leaks? And it turns out that we can.

new in C++ will be considered as an add method. delete will be considered as a sub method.

First example is the most simplest one:

int main ()

{

auto item = new Item {"glasses"};

delete item;

}Item is the same from our previous examples. We allocated and initialize it and delete it. And we have a balanced scope inside main.

For more complex rules for loop paths and call paths, where balancing is considering branches and methods. The same rules applies for initialization and deallocation.

Lets consider our storage class again:

class Storage {

public:

vector<Item*> items;

Storage() {}

void addItem(string name) {

items.push_back(new Item {name});

}

void deleteItem(int index) {

auto item = items.begin() + index;

objects.erase(item);

delete *item;

}

};We have an initialization expression on our add method:

items.push_back(new Item {name});Because it is references an index in items by push_back, our sub method also need to reference an index in items in order to reach a balance. And that is exactly what we do:

void deleteItem(int index) {

auto item = items.begin() + index;

objects.erase(item);

delete *item;

}You can have two reference to the same storage instnace:

Storage* storage = new Storage();

void addToStorage(Item* item)

{

storage->addItem(item);

}

void deleteFromStorage(Item* item)

{

storage->deleteItem(item);

}

int main ()

{

auto item = new Item {"glasses"};

Storage* tmpStorage = storage;

tmpStorage->addItem(item);

storage->deleteItem(item);

tmpStorage->showItems();

delete item;

}Notice, if you have two reference to two separate store, you would not have balance if you called the add method on one, and the delete method on the other.

Sveral stores can also add the same objects, as long as balance is made.

Storage* storage1 = new Storage();

Storage* storage2 = new Storage();

int main ()

{

auto item = new Item {"glasses"};

storage1->addItem(item);

storage1->deleteItem(item);

storage2->addItem(item);

storage2->deleteItem(item);

delete item;

}Notice that, each addItem call needs to match with a deleteItem call on each store.

We some times, need to deal with multiple references of the same class of objects. The compiler will not pass the code if there is two classifications that have the same name. This is because we want to associate one type of allocation/deallocation of resource with one identifier. This will make code more safe, because one type of allocation cannot be checked against another type of deallocation.

In order to satisfy our compiler we would need to give our classifications some aliases. And the syntax for aliasing a method classification is:

AddSubAliasClassification :: add | sub Name as Alias CallExpression

Lets go ahead and add these classifications:

import { View } from './view';

class SubView {

private view: View;

private anotherView: View;

// add UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

// add UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

public show() {

add UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method.

add UserChangeTitleEventCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

this.anotherView = new View(this.user); // Add method.

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherSubView

this.onDestroy(() => {

this.removeView(); // Sub method.

this.removeAnotherView(); // Sub method.

});

}

private onDestroy(callback: () => void) {

this.deleteButton.addEventListener(callback);

}

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

public removeView() {

sub UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

this.view.removeUser(); // Sub method.

this.view = null;

}

// off UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

public removeAnotherView() {

off UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

this.anotherView.removeUser(); // Sub method.

this.subView = null;

}

}Notice, that the anonymous lambda function will inherit the classifications:

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

this.onDestroy(() => {

this.removeView(); // Sub method.

this.removeAnotherView(); // Sub method.

});This is due to the fact that the lambda's function's scope does not have matching add method calls for the current sub method calls. Also, since this.onDestroy is a method which accept callbacks, and it will balance the containing scope:

add UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnView

this.view = new View(this.user); // Add method.

add UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

this.anotherView = new View(this.user); // Add method.So in other words, The above code will compile. It also causes no memory leaks.

One could also resolve the name collisioning simple by looking at the left operand.

For our add method we got the following code:

add UserChangeTitleEventCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbackOnAnotherView

this.anotherView = new View(this.user); // Add method.We could just have written:

this.anotherView = new View(this.user); // Add method.And look at the left operand this.anotherView to match a corresponding sub method call.

Because we assigned to this.anotherView, any kind of sub method classification must call a sub method on this.anotherView. This is to check that the add method call matches the corresponding sub method call. And that is exactly what we have done in our example:

this.anotherView.removeUser(); // Sub method.Auto-aliasing makes code less bloated. Also a programming language designer can skip having any aliasing at all and only have everything auto aliasing.

When dealing with multiple simultaneous addition or subtraction of objects, it is good practice to have already balanced method calls on constructors or methods.

import { View } from './view';

class SubView {

private views: View[] = [];

public show() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

this.views.push(new View(this.user)); // The constructor is already balanced. So the compiler will not complain.

}

}

}Because we don't need to deal with an even more complex balancing of add-sub methods.

For various reason, if one cannot use balanced methods/constructors. The classifications conventions works as before. An unmatched add or sub method call annotates the containing method. Even on a for loop below:

class SubView {

private views: View[] = [];

// add UserChangeTitleCallback

public show() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

add UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbacks

this.views.push(new View(this.user));

}

}

}As before, we would need to have a matching sub method to satisfy our compiler:

class SubView {

private views: View[] = [];

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbacks

public remove() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

sub UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbacks

this.views[i].removeUser();

}

this.views = [];

}

}In the above example, this.views[i].removeUser(); is a sub method and since there are no add method that balances it. It annotates the containing method remove.

Now, our whole class will look like this:

class SubView {

private views: View[] = [];

// add UserChangeTitleCallback

public show() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

add UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbacks

this.views.push(new View(this.user));

}

}

private onDestroy(callback: () => void) {

this.deleteAllButton.addEventListener(callback);

}

// sub UserChangeTitleCallbacks

public remove() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

sub UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbacks

this.views[i].removeUser();

}

this.views = [];

}

}Note, there is no compile error, even though the number of loops in remove is not matched with show. Like for instance, we could have only 9 loops instead of 10:

for (let i = 0; i < 9; i++) {// Loop only 9 elements and not 10 causes another memory leak.

off UserChangeTitleCallback as UserChangeTitleCallbacks

this.subView[i].removeUser();

}Notice, that adding multiple objects simultaneously and at least having a method of subtracting them, even though the the subtraction method only subtracts one from the storage. It still satisfy our balance definition. Any objects added can eventually be subtracted.

One could ask why not annotating the source of the memory leak directly instead of classifying the methods? It's possible and it is even more safer. Lets revisit our EventEmitter class:

export class EventEmitter {

public eventCallbacks: EventCallbacks = {}

}Our general concept so far, is that for every method for addition of objects, there should exists at least one matching method for subtraction of objects. We can safely say that new assignements will increase the elements count. But also, in the event emitter case, array element additions. With static code analysis we can also make sure that elements are added or subtracted. Before it was upto the developer to manually annotate and implement the method. But nothing stops the developer to implement a sub method which increases the elements count.

For the add-sub methods the following holds true:

Add methods: Adds 0 or more elements to the storage.

Sub methods: Subtracts 0 or more elements to the storage.

Notice: The range is crucial, only 0 will not satisfy any of the definitions.

And let it be our definitions for our add-sub methods for our case.

We also want to introduce a new syntax to annotate a storage:

AddSubClassification ::

balance Storage as ElementName StorageDeclaration

Storage ::

Type, { IndexExpression }

IndexExpression ::

"[", Key ,"]"

StorageDeclaration is a property declaration in a class. ElementName is the name of an element in StorageDeclaration. The Key above is an arbitrary identifier. It does not need to match anything. It is just there for readability. Though the whole index expression indicates it should go one or more levels deeper to indicate an element addition or subtraction. More on this later.

Lets annotate our eventCallbacks store:

export class User extends EventEmitter {

balance EventCallbacks[event] as EventCallback

public eventCallbacks: EventCallbacks = {}

}The expression:

balance EventCallbacks[event] as EventCallbackindicates that only elements added/subtracted to eventCallbacks[event](and not eventCallbacks) will be considered.

Notice, also when we now have an annotation for the storage. We don't need to classify methods with add|sub NAME anymore.

Now, we can staticly analyse the register method, which is suppose to be an add method:

public register(event: string, callback: Callback) {

if (!this.eventCallbacks[event]) {

this.eventCallbacks[event] = [];

}

this.eventCallbacks[event].push(callback);

}Lets check out our if statement and body:

if (!this.eventCallbacks[event]) {

this.eventCallbacks[event] = [];

}An assignment adds 0 or 1 new elements to the store. Though we have only specified that an index element of this.eventCallbacks[event] are storage elements. So the above code does not add anything to store.

In comparison, the following expression adds one element to the store:

this.eventCallbacks[event].push(callback);So in all, we can safely say that the method adds 1 element to the store eventCallbacks each time the method is called. And it satisfies our add method definition above.

Now, lets examine our unregister method:

public unregister(event: string, callback: Callback): void {

let callbacks = this.eventCallbacks[event].length;

for (let i = 0; i < callback.length; i++) {

if (this.eventCallbacks[event][i] === callback) {

this.eventCallbacks[event].splice(i, 1);

}

}

}We can statically confirm that this method subtracts 0 or 1 elements from our store with the following expression(even though it is encapsulated in a for-loop and an if statement block):

this.eventCallbacks[event].splice(i, 1);Please also notice that our add method adds 1 element and our sub method subtracts 0 or 1 element for each call. It still correctly satisfies our balance definition, because an addition of an element has the potential of being subtracted, given an infinite amount of time.

Lets also examine a false add-sub method example. Lets take our emit method as an example:

public emit(event: string, args: any[]) {

if (this.eventCallbackStore[event]) {

for (let callback of this.eventCallbackStore[event]) {

callback.apply(null, args);

}

}

}There is no expression in above that increases our elements count in our store. There exists an index look up such as this.eventCallbackStore[event], though it does not add any elements. So we can safely say that this method does not satisfy any of our add-sub method definitions above.

We only considered arrays so far. Though any type that can grow the heap can be annotated.

When we arrived at our final syntax. We discovered that we could annotate a property and let static analysis discover our toggle methods. Let us illustrate what this means:

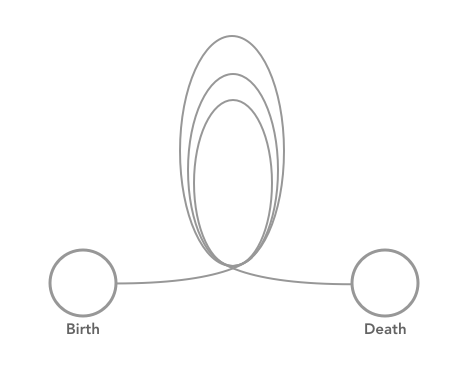

When we have a memory leak. Essentially what it means is that our heap object graph can grow to an infinite amount of nodes, starting from some node:

And we want to statically annotate that any consumer of this node needs to call an add and sub methods:

We have showed that using balancing of add and sub methods can provide a powerful way of checking applications to prevent memory leaks. Though it remains to be implemented and tested on a real programming language.