| title | thumbnail | authors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cosmopedia: how to create large-scale synthetic data for pre-training Large Language Models |

/blog/assets/cosmopedia/thumbnail.png |

|

In this blog post, we outline the challenges and solutions involved in generating a synthetic dataset with billions of tokens to replicate Phi-1.5, leading to the creation of Cosmopedia. Synthetic data has become a central topic in Machine Learning. It refers to artificially generated data, for instance by large language models (LLMs), to mimic real-world data.

Traditionally, creating datasets for supervised fine-tuning and instruction-tuning required the costly and time-consuming process of hiring human annotators. This practice entailed significant resources, limiting the development of such datasets to a few key players in the field. However, the landscape has recently changed. We've seen hundreds of high-quality synthetic fine-tuning datasets developed, primarily using GPT-3.5 and GPT-4. The community has also supported this development with numerous publications that guide the process for various domains, and address the associated challenges [1][2][3][4][5].

Figure 1. Datasets on Hugging Face hub with the tag synthetic.

However, this is not another blog post on generating synthetic instruction-tuning datasets, a subject the community is already extensively exploring. We focus on scaling from a few thousand to millions of samples that can be used for pre-training LLMs from scratch. This presents a unique set of challenges.

Microsoft pushed this field with their series of Phi models [6][7][8], which were predominantly trained on synthetic data. They surpassed larger models that were trained much longer on web datasets. Phi-2 was downloaded over 617k times in the past month and is among the top 20 most-liked models on the Hugging Face hub.

While the technical reports of the Phi models, such as the “Textbooks Are All You Need” paper, shed light on the models’ remarkable performance and creation, they leave out substantial details regarding the curation of their synthetic training datasets. Furthermore, the datasets themselves are not released. This sparks debate among enthusiasts and skeptics alike. Some praise the models' capabilities, while critics argue they may simply be overfitting benchmarks; some of them even label the approach of pre-training models on synthetic data as « garbage in, garbage out». Yet, the idea of having full control over the data generation process and replicating the high-performance of Phi models is intriguing and worth exploring.

This is the motivation for developing Cosmopedia, which aims to reproduce the training data used for Phi-1.5. In this post we share our initial findings and discuss some plans to improve on the current dataset. We delve into the methodology for creating the dataset, offering an in-depth look at the approach to prompt curation and the technical stack. Cosmopedia is fully open: we release the code for our end-to-end pipeline, the dataset, and a 1B model trained on it called cosmo-1b. This enables the community to reproduce the results and build upon them.

Besides the lack of information about the creation of the Phi datasets, another downside is that they use proprietary models to generate the data. To address these shortcomings, we introduce Cosmopedia, a dataset of synthetic textbooks, blog posts, stories, posts, and WikiHow articles generated by Mixtral-8x7B-Instruct-v0.1. It contains over 30 million files and 25 billion tokens, making it the largest open synthetic dataset to date.

Heads up: If you are anticipating tales about deploying large-scale generation tasks across hundreds of H100 GPUs, in reality most of the time for Cosmopedia was spent on meticulous prompt engineering.

Generating synthetic data might seem straightforward, but maintaining diversity, which is crucial for optimal performance, becomes significantly challenging when scaling up. Therefore, it's essential to curate diverse prompts that cover a wide range of topics and minimize duplicate outputs, as we don’t want to spend compute on generating billions of textbooks only to discard most because they resemble each other closely. Before we launched the generation on hundreds of GPUs, we spent a lot of time iterating on the prompts with tools like HuggingChat. In this section, we'll go over the process of creating over 30 million prompts for Cosmopedia, spanning hundreds of topics and achieving less than 1% duplicate content.

Cosmopedia aims to generate a vast quantity of high-quality synthetic data with broad topic coverage. According to the Phi-1.5 technical report, the authors curated 20,000 topics to produce 20 billion tokens of synthetic textbooks while using samples from web datasets for diversity, stating:

We carefully selected 20K topics to seed the generation of this new synthetic data. In our generation prompts, we use samples from web datasets for diversity.

Assuming an average file length of 1000 tokens, this suggests using approximately 20 million distinct prompts. However, the methodology behind combining topics and web samples for increased diversity remains unclear.

We combine two approaches to build Cosmopedia’s prompts: conditioning on curated sources and conditioning on web data. We refer to the source of the data we condition on as “seed data”.

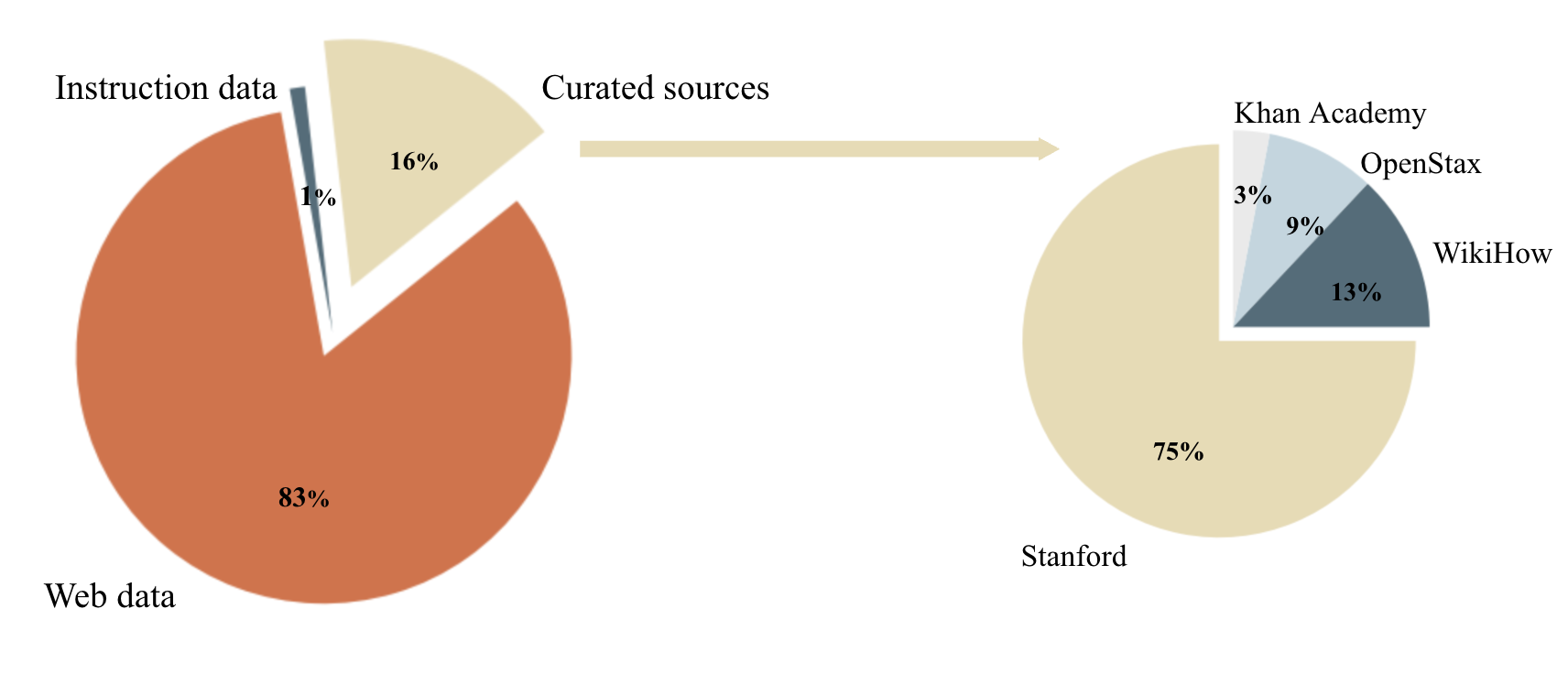

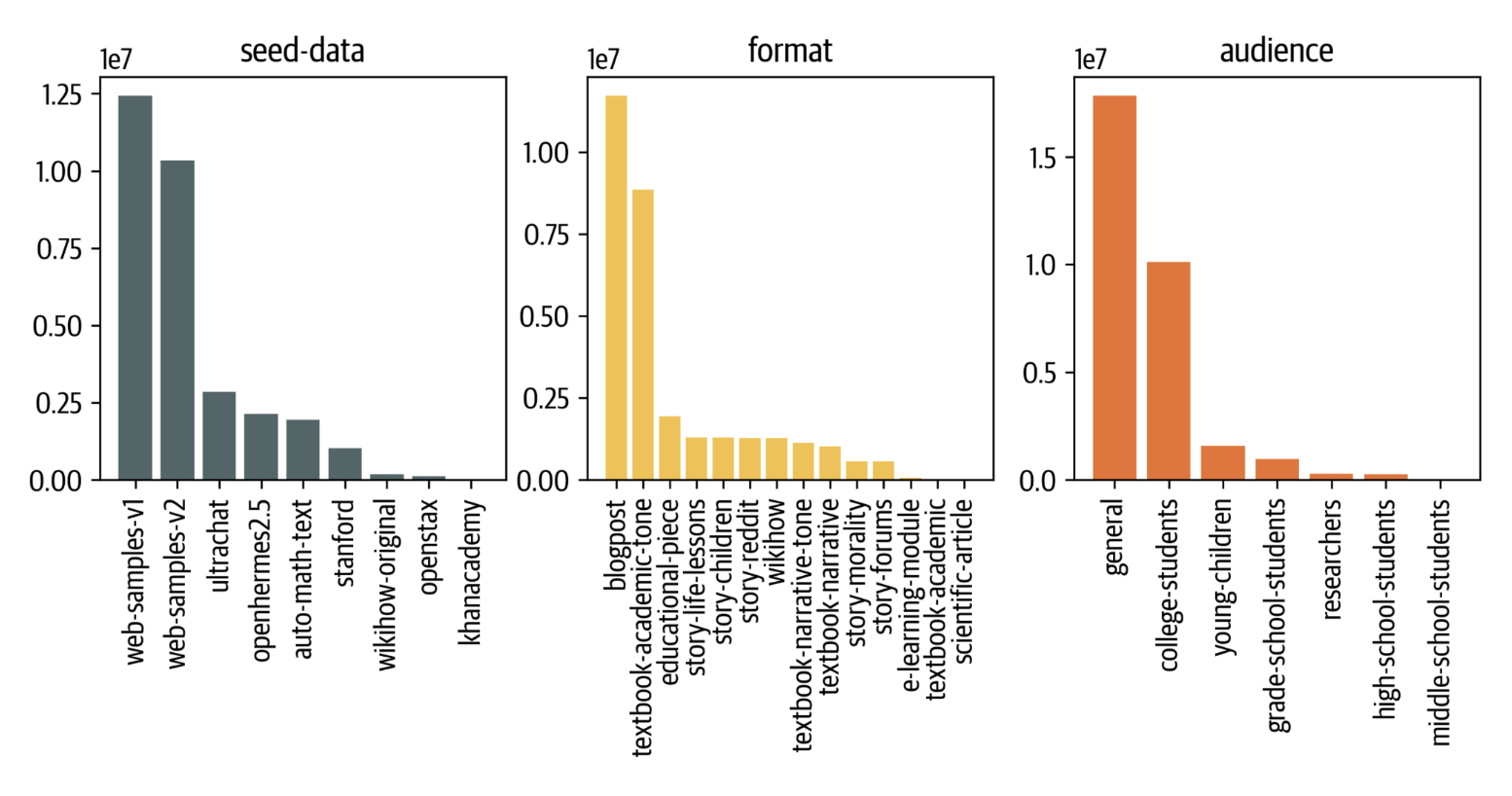

Figure 2. The distribution of data sources for building Cosmopedia prompts (left plot) and the distribution of sources inside the Curated sources category (right plot).

We use topics from reputable educational sources such as Stanford courses, Khan Academy, OpenStax, and WikiHow. These resources cover many valuable topics for an LLM to learn. For instance, we extracted the outlines of various Stanford courses and constructed prompts that request the model to generate textbooks for individual units within those courses. An example of such a prompt is illustrated in figure 3.

Although this approach yields high-quality content, its main limitation is scalability. We are constrained by the number of resources and the topics available within each source. For example, we can extract only 16,000 unique units from OpenStax and 250,000 from Stanford. Considering our goal of generating 20 billion tokens, we need at least 20 million prompts!

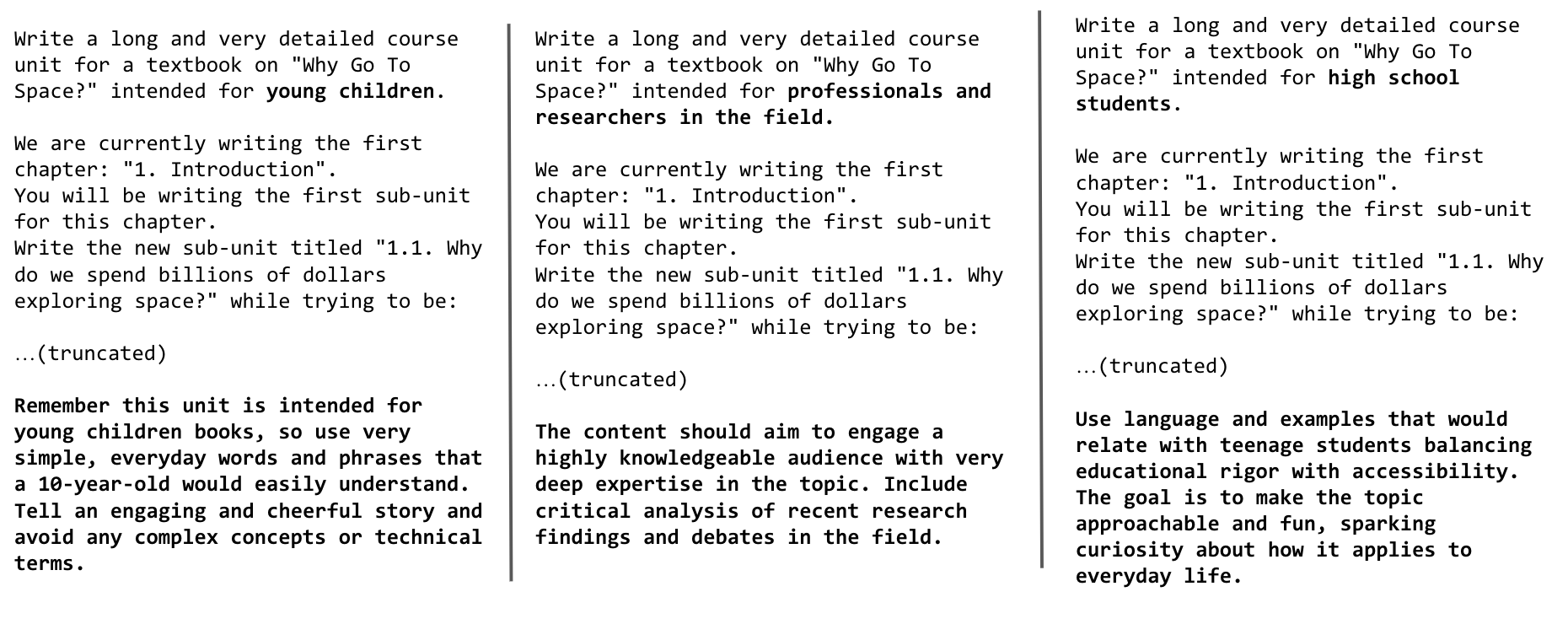

One strategy to increase the variety of generated samples is to leverage the diversity of audience and style: a single topic can be repurposed multiple times by altering the target audience (e.g., young children vs. college students) and the generation style (e.g., academic textbook vs. blog post). However, we discovered that simply modifying the prompt from "Write a detailed course unit for a textbook on 'Why Go To Space?' intended for college students" to "Write a detailed blog post on 'Why Go To Space?'" or "Write a textbook on 'Why Go To Space?' for young children" was insufficient to prevent a high rate of duplicate content. To mitigate this, we emphasized changes in audience and style, providing specific instructions on how the format and content should differ.

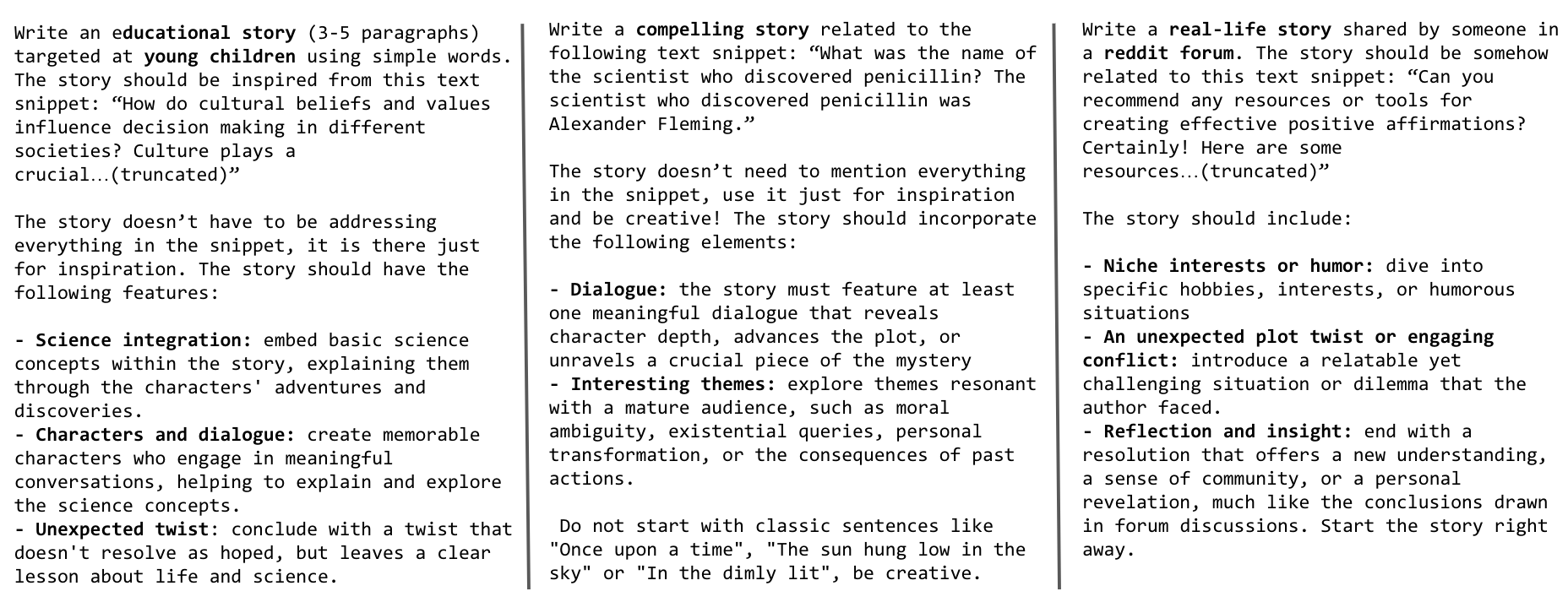

Figure 3 illustrates how we adapt a prompt based on the same topic for different audiences.

Figure 3. Prompts for generating the same textbook for young children vs for professionals and researchers vs for high school students.

By targeting four different audiences (young children, high school students, college students, researchers) and leveraging three generation styles (textbooks, blog posts, wikiHow articles), we can get up to 12 times the number of prompts. However, we might want to include other topics not covered in these resources, and the small volume of these sources still limits this approach and is very far from the 20+ million prompts we are targeting. That’s when web data comes in handy; what if we were to generate textbooks covering all the web topics? In the next section, we’ll explain how we selected topics and used web data to build millions of prompts.

Using web data to construct prompts proved to be the most scalable, contributing to over 80% of the prompts used in Cosmopedia. We clustered millions of web samples, using a dataset like RefinedWeb, into 145 clusters, and identified the topic of each cluster by providing extracts from 10 random samples and asking Mixtral to find their common topic. More details on this clustering are available in the Technical Stack section.

We inspected the clusters and excluded any deemed of low educational value. Examples of removed content include explicit adult material, celebrity gossip, and obituaries. The full list of the 112 topics retained and those removed can be found here.

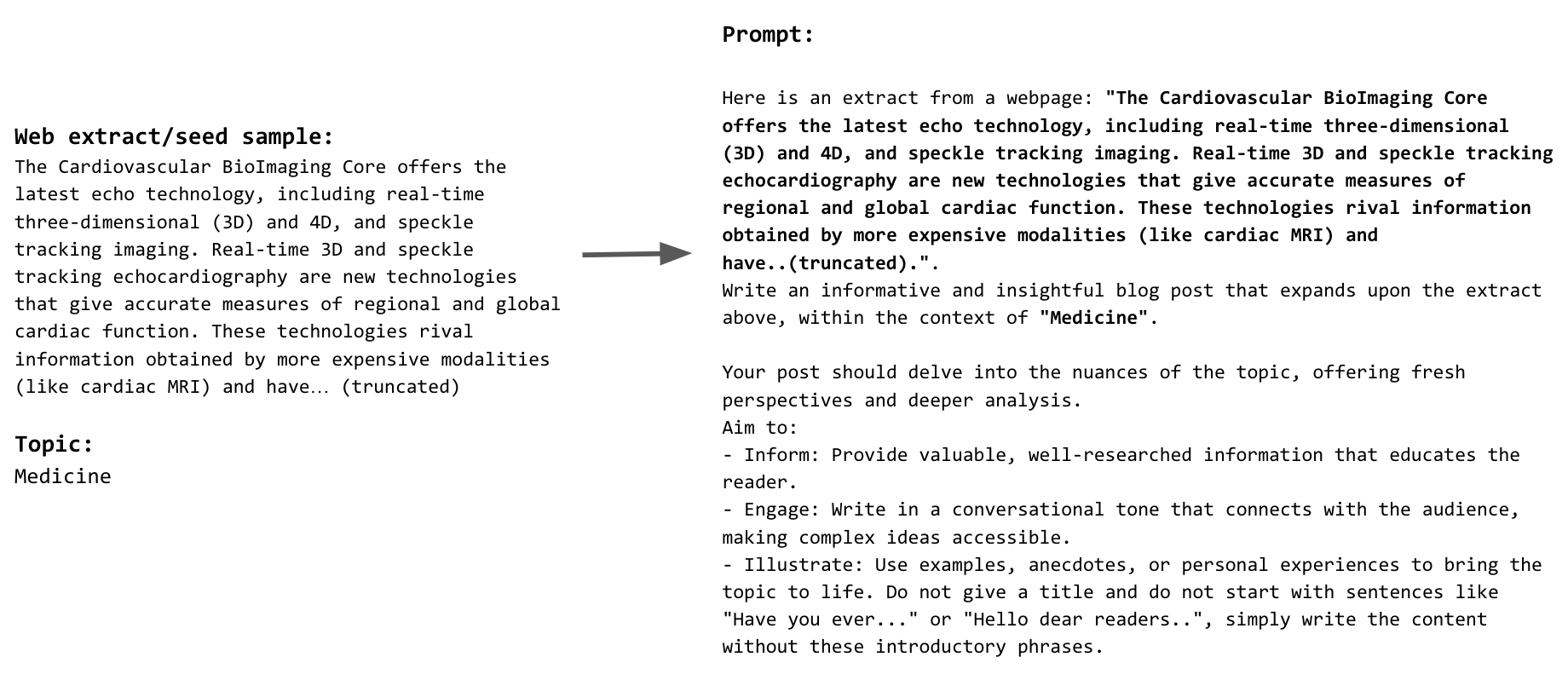

We then built prompts by instructing the model to generate a textbook related to a web sample within the scope of the topic it belongs to based on the clustering. Figure 4 provides an example of a web-based prompt. To enhance diversity and account for any incompleteness in topic labeling, we condition the prompts on the topic only 50% of the time, and change the audience and generation styles, as explained in the previous section. We ultimately built 23 million prompts using this approach. Figure 5 shows the final distribution of seed data, generation formats, and audiences in Cosmopedia.

Figure 4. Example of a web extract and the associated prompt.

Figure 5. The distribution of seed data, generation format and target audiences in Cosmopedia dataset.

In addition to random web files, we used samples from AutoMathText, a carefully curated dataset of Mathematical texts with the goal of including more scientific content.

In our initial assessments of models trained using the generated textbooks, we observed a lack of common sense and fundamental knowledge typical of grade school education. To address this, we created stories incorporating day-to-day knowledge and basic common sense using texts from the UltraChat and OpenHermes2.5 instruction-tuning datasets as seed data for the prompts. These datasets span a broad range of subjects. For instance, from UltraChat, we used the "Questions about the world" subset, which covers 30 meta-concepts about the world. For OpenHermes2.5, another diverse and high-quality instruction-tuning dataset, we omitted sources and categories unsuitable for storytelling, such as glaive-code-assist for programming and camelai for advanced chemistry. Figure 6 shows examples of prompts we used to generate these stories.

Figure 6. Prompts for generating stories from UltraChat and OpenHermes samples for young children vs a general audience vs reddit forums.

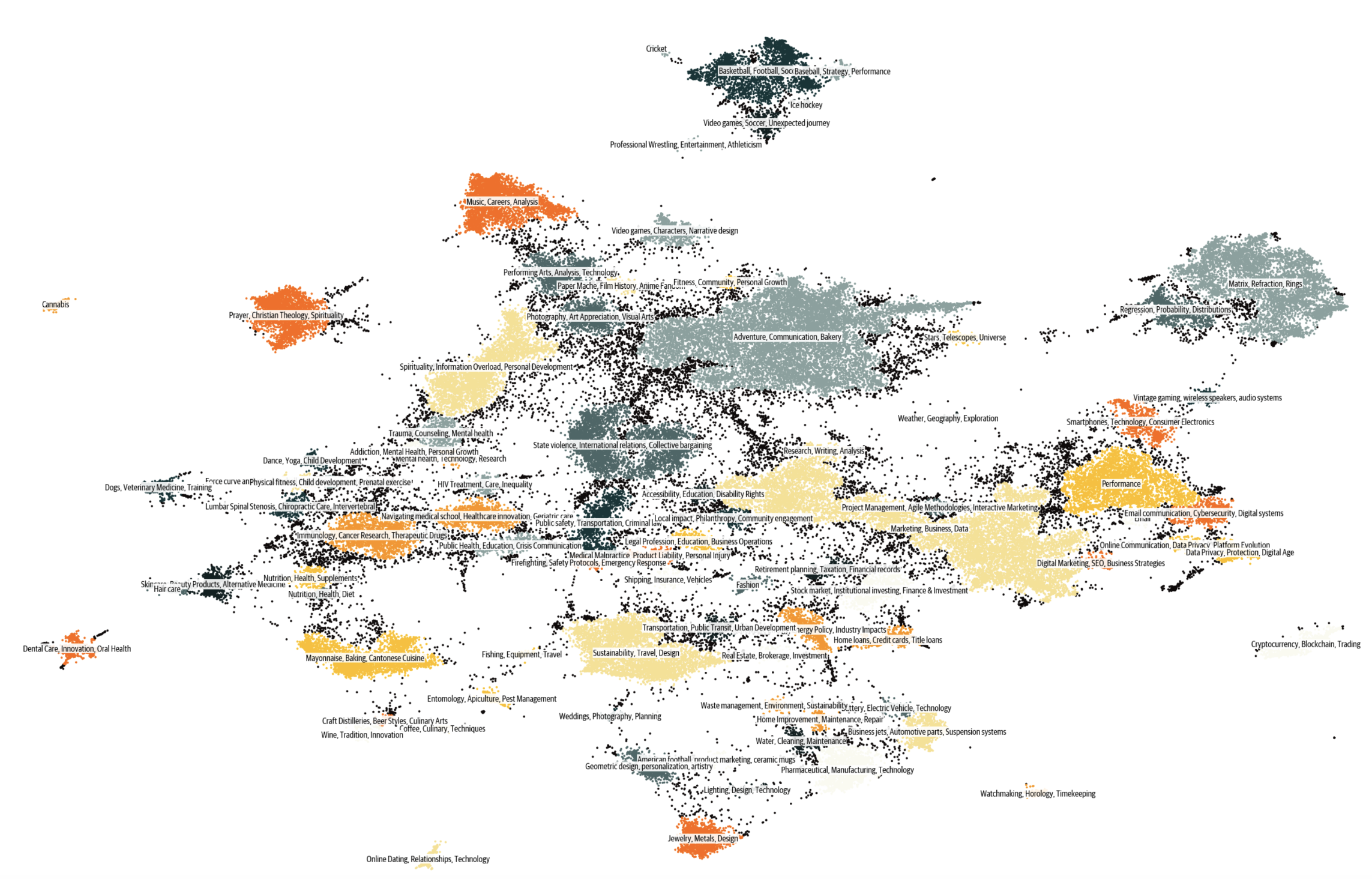

That's the end of our prompt engineering story for building 30+ million diverse prompts that provide content with very few duplicates. The figure below shows the clusters present in Cosmopedia, this distribution resembles the clusters in the web data. You can also find a clickable map from Nomic here.

Figure 7. The clusters of Cosmopedia, annotated using Mixtral.

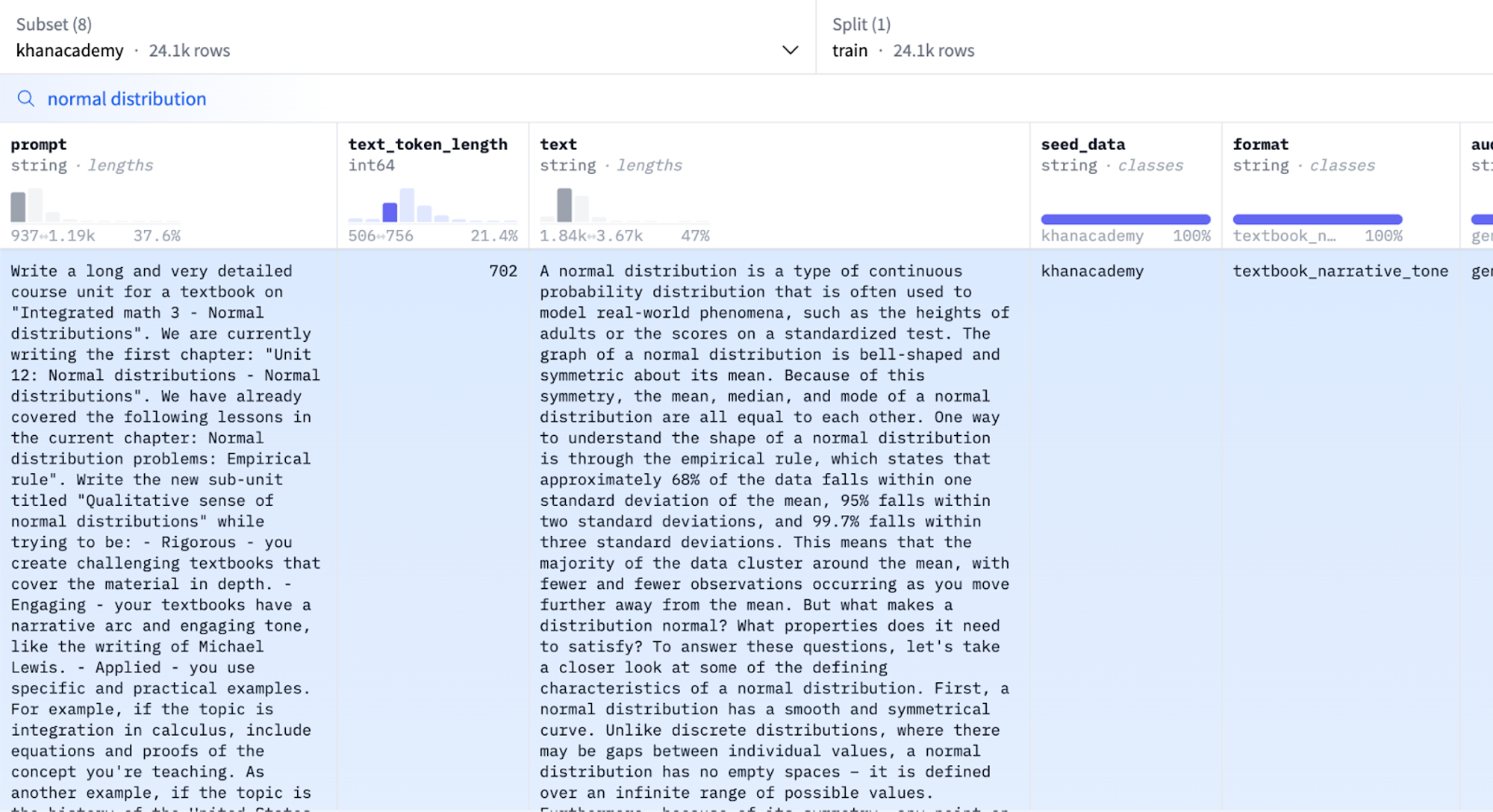

You can use the dataset viewer to investigate the dataset yourself:

Figure 8. Cosmopedia's dataset viewer.

We release all the code used to build Cosmopedia in: https://github.com/huggingface/cosmopedia

In this section we'll highlight the technical stack used for text clustering, text generation at scale and for training cosmo-1b model.

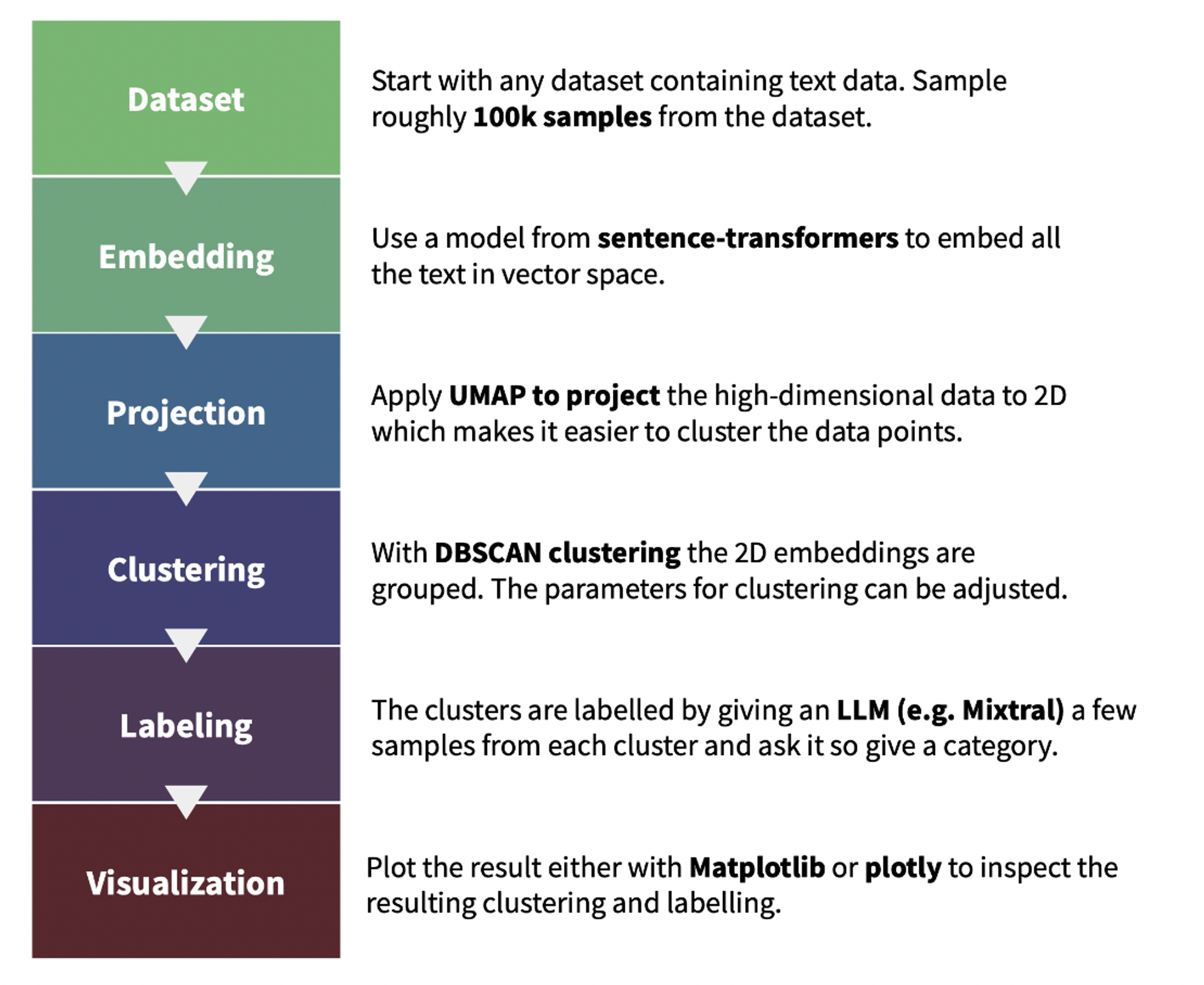

We used text-clustering repository to implement the topic clustering for the web data used in Cosmopedia prompts. The plot below illustrates the pipeline for finding and labeling the clusters. We additionally asked Mixtral to give the cluster an educational score out of 10 in the labeling step; this helped us in the topics inspection step. You can find a demo of the web clusters and their scores in this demo.

Figure 9. The pipleline of text-clustering.

We leverage the llm-swarm library to generate 25 billion tokens of synthetic content using Mixtral-8x7B-Instruct-v0.1. This is a scalable synthetic data generation tool using local LLMs or inference endpoints on the Hugging Face Hub. It supports TGI and vLLM inference libraries. We deployed Mixtral-8x7B locally on H100 GPUs from the Hugging Face Science cluster with TGI. The total compute time for generating Cosmopedia was over 10k GPU hours.

Here's an example to run generations with Mixtral on 100k Cosmopedia prompts using 2 TGI instances on a Slurm cluster:

# clone the repo and follow installation requirements

cd llm-swarm

python ./examples/textbooks/generate_synthetic_textbooks.py \

--model mistralai/Mixtral-8x7B-Instruct-v0.1 \

--instances 2 \

--prompts_dataset "HuggingFaceTB/cosmopedia-100k" \

--prompt_column prompt \

--max_samples -1 \

--checkpoint_path "./tests_data" \

--repo_id "HuggingFaceTB/generations_cosmopedia_100k" \

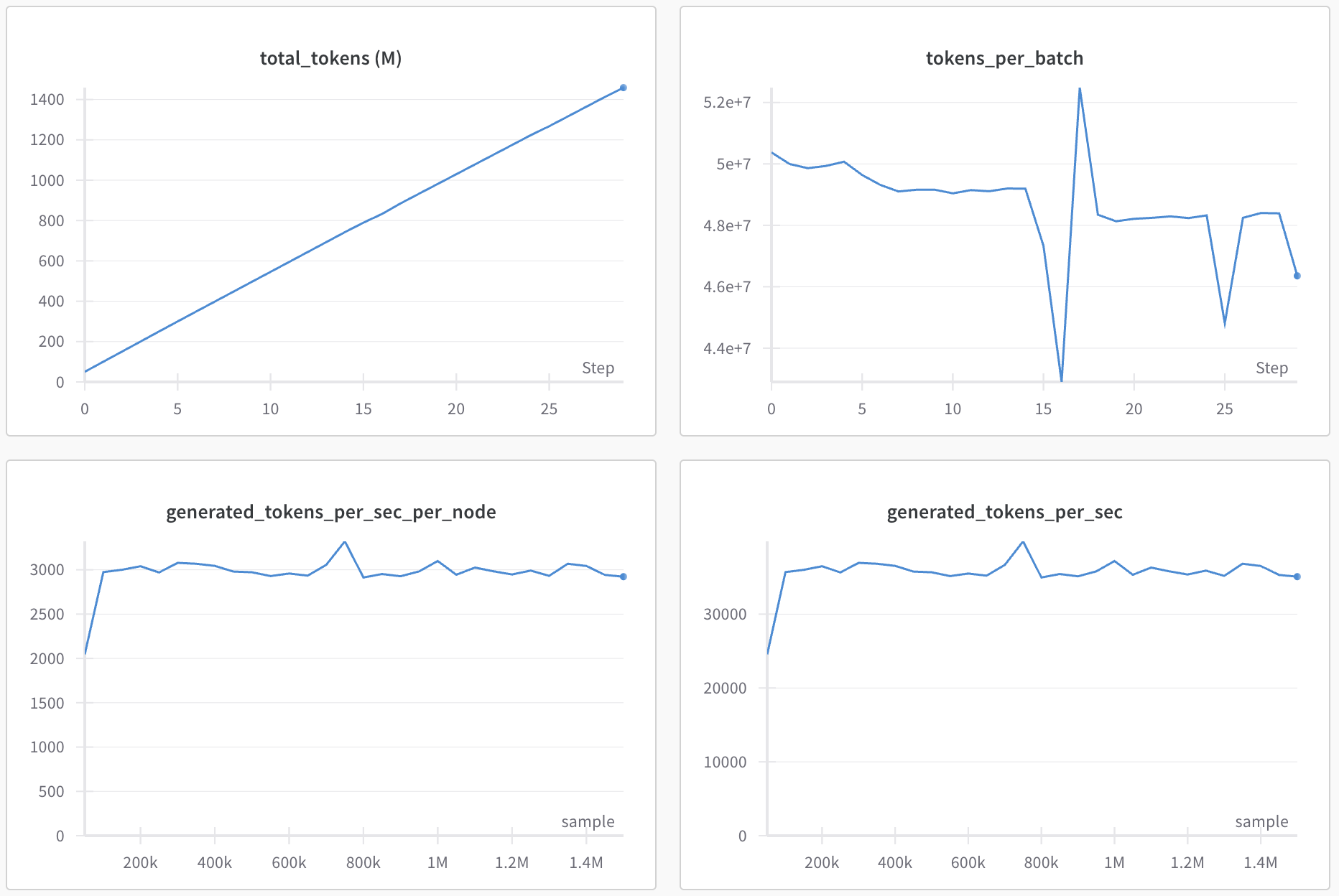

--checkpoint_interval 500You can even track the generations with wandb to monitor the throughput and number of generated tokens.

Figure 10. Wandb plots for an llm-swarm run.

Note:

We used HuggingChat for the initial iterations on the prompts. Then, we generated a few hundred samples for each prompt using llm-swarm to spot unusual patterns. For instance, the model used very similar introductory phrases for textbooks and frequently began stories with the same phrases, like "Once upon a time" and "The sun hung low in the sky". Explicitly asking the model to avoid these introductory statements and to be creative fixed the issue; they were still used but less frequently.

Given that we generate synthetic data, there is a possibility of benchmark contamination within the seed samples or the model's training data. To address this, we implement a decontamination pipeline to ensure our dataset is free of any samples from the test benchmarks.

Similar to Phi-1, we identify potentially contaminated samples using a 10-gram overlap. After retrieving the candidates, we employ difflib.SequenceMatcher to compare the dataset sample against the benchmark sample. If the ratio of len(matched_substrings) to len(benchmark_sample) exceeds 0.5, we discard the sample. This decontamination process is applied across all benchmarks evaluated with the Cosmo-1B model, including MMLU, HellaSwag, PIQA, SIQA, Winogrande, OpenBookQA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge.

We report the number of contaminated samples removed from each dataset split, as well as the number of unique benchmark samples that they correspond to (in brackets):

| Dataset group | ARC | BoolQ | HellaSwag | PIQA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| web data + stanford + openstax | 49 (16) | 386 (41) | 6 (5) | 5 (3) |

| auto_math_text + khanacademy | 17 (6) | 34 (7) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| stories | 53 (32) | 27 (21) | 3 (3) | 6 (4) |

We find less than 4 contaminated samples for MMLU, OpenBookQA and WinoGrande.

We trained a 1B LLM using Llama2 architecure on Cosmopedia to assess its quality: https://huggingface.co/HuggingFaceTB/cosmo-1b.

We used datatrove library for data deduplication and tokenization, nanotron for model training, and lighteval for evaluation.

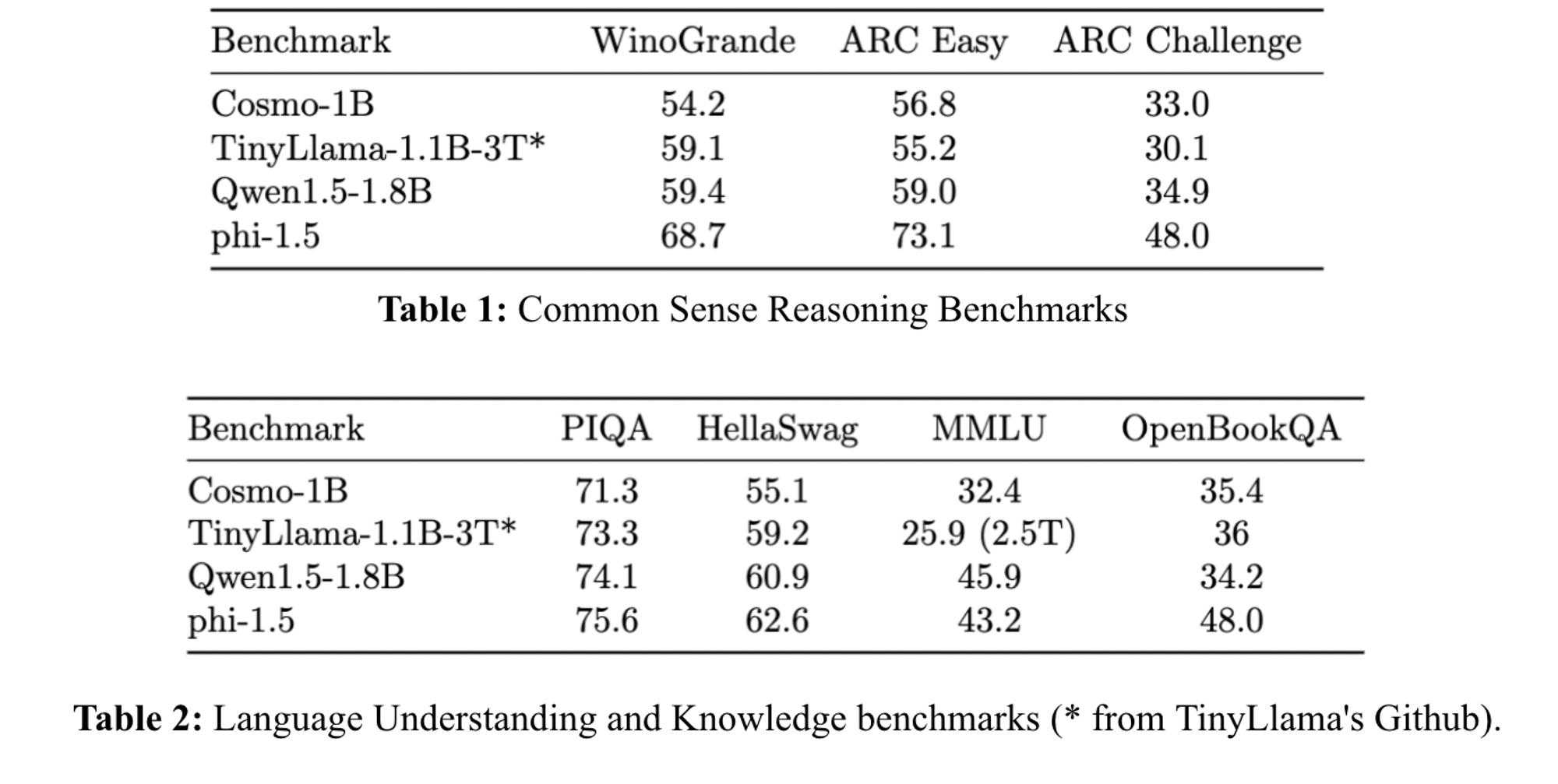

The model performs better than TinyLlama 1.1B on ARC-easy, ARC-challenge, OpenBookQA, and MMLU and is comparable to Qwen-1.5-1B on ARC-challenge and OpenBookQA. However, we notice some performance gaps compared to Phi-1.5, suggesting a better synthetic generation quality, which can be related to the LLM used for generation, topic coverage, or prompts.

Figure 10. Evaluation results of Cosmo-1B.

In this blog post, we outlined our approach for creating Cosmopedia, a large synthetic dataset designed for pre-training models, with the goal of replicating the Phi datasets. We highlighted the significance of meticulously crafting prompts to cover a wide range of topics, ensuring the generation of diverse content. Additionally, we have shared and open-sourced our technical stack, which allows for scaling the generation process across hundreds of GPUs.

However, this is just the initial version of Cosmopedia, and we are actively working on enhancing the quality of the generated content. The accuracy and reliability of the generations largely depends on the model used in the generation. Specifically, Mixtral may sometimes hallucinate and produce incorrect information, for example when it comes to historical facts or mathematical reasoning within the AutoMathText and KhanAcademy subsets. One strategy to mitigate the issue of hallucinations is the use of retrieval augmented generation (RAG). This involves retrieving information related to the seed sample, for example from Wikipedia, and incorporating it into the context. Hallucination measurement methods could also help assess which topics or domains suffer the most from it [9]. It would also be interesting to compare Mixtral’s generations to other open models.

The potential for synthetic data is immense, and we are eager to see what the community will build on top of Cosmopedia.

[1] Ding et al. Enhancing Chat Language Models by Scaling High-quality Instructional Conversations. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.14233

[2] Wei et al. Magicoder: Source Code Is All You Need. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.02120

[3] Toshniwal et al. OpenMathInstruct-1: A 1.8 Million Math Instruction Tuning Dataset. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.10176

[4] Xu et al. WizardLM: Empowering Large Language Models to Follow Complex Instructions. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.12244

[5] Moritz Laurer. Synthetic data: save money, time and carbon with open source. URL https://huggingface.co/blog/synthetic-data-save-cost

[6] Gunasekar et al. Textbooks Are All You Need. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.11644

[7] Li et al. Textbooks are all you need ii: phi-1.5 technical report. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.05463

[8] Phi-2 blog post. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/phi-2-the-surprising-power-of-small-language-models/

[9] Manakul, Potsawee and Liusie, Adian and Gales, Mark JF. Selfcheckgpt: Zero-resource black-box hallucination detection for generative large language models. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08896