-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 16

Learn from Mac OS X how to suck less at system integration #30

Comments

Prior ArtOther systemsClassic MacOSIn the original 1984 Macintosh desktop, every application was a single file that could be freely moved around in the file system. No installation was necessary. The system used a desktop database that automatically associated files with the applications that had created them (using the type and creator resrouces). The desktop information was stored in two files, Source: Wikipedia Note that when after the merger with NeXT, Apple went on to create Mac OS X, they explicitly stated in 2000 (16 years after Classic Mac OS) that it was their objective to match that level of simplicity for modern applications. (Source: Apple WWDC 2000 Session 144 - Mac OS X: Application Packaging and Document Typing, 3:22) NeXTStep, NeXTSTEP, OPENSTEPNeXTSTEP was an operating system launched by Steve Jobs' NeXT Computer in the late 1980s and is the predecessor to today's macOS. It had a concise concept application system integration. Let's the system describe itself: Source: https://medium.com/@probonopd/make-it-simple-linux-desktop-usability-part-6-1c03de7c00a9 This is how NeXT Workspace Manager (in 1989) automatically handled file associations using the Apps directory. Note that no files (other than the application itself) have to be copied around, no databases have to be manually triggered. The applications themselves were directories that the file manager showed like files, but the terminal showed like directories: Source: https://medium.com/@probonopd/make-it-simple-linux-desktop-usability-part-6-1c03de7c00a9 NeXTSTEP 1.0 filesystem in Terminal vs. Directory Browser GUI Mac OS XWhen Mac OS X was created around 2000, Application Packaging and Document Typing merged the simplicity of Classic Mac OS single-file applications with the benefits of NeXT-style application directories, and introduced a new bundle format and Launch Services. This is explained in detail in

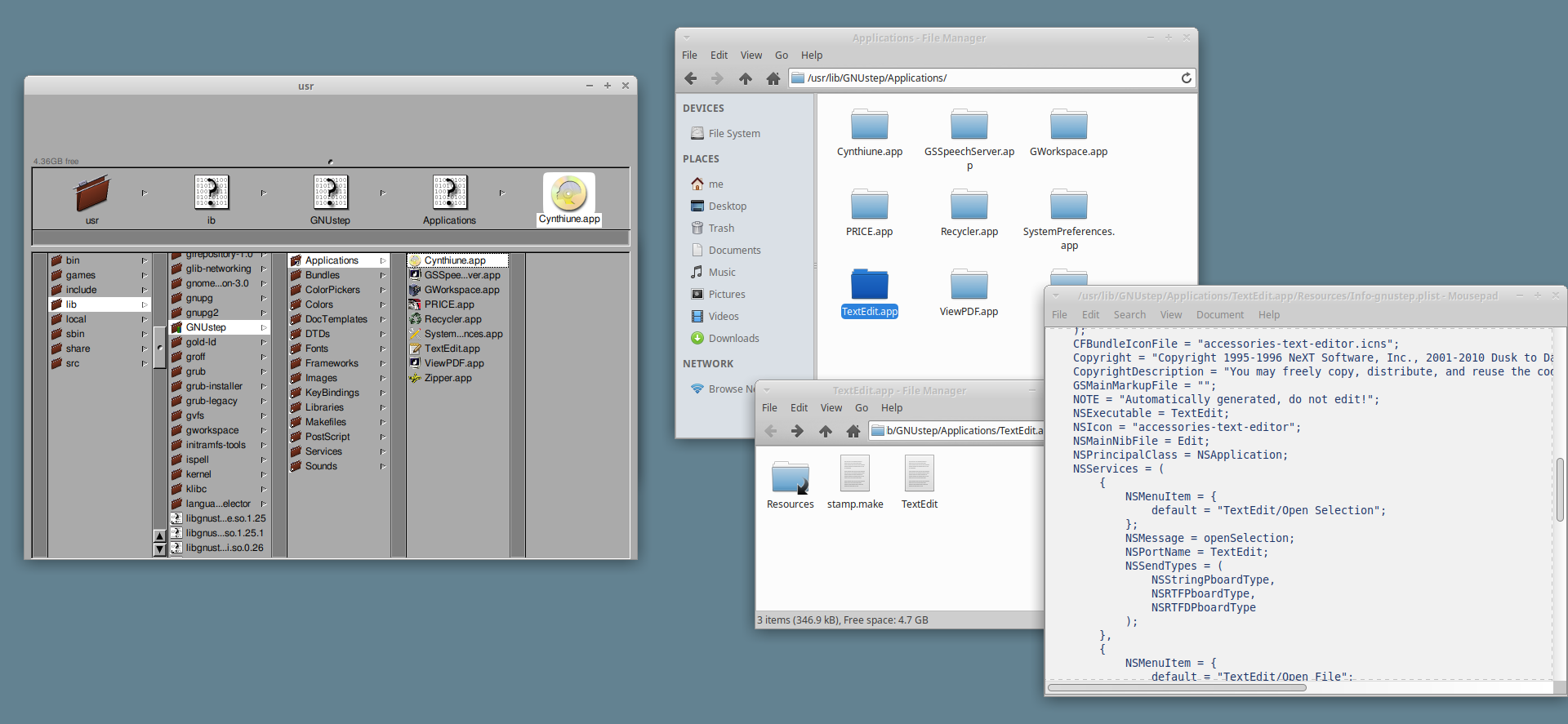

Today's macOS, it is still possible to associate a single file to a certain application, and for the user to override this on a per-file basis. This is not possible on Linux? Source: https://eclecticlight.co/2017/08/11/launch-services-database-problems-correcting-and-rebuilding/ The Launch Services Daemon, "Desktop Linux"What we call "Desktop Linux" is more correctly described as the X Desktop, since it can run on various kernels, including Linux. But as the vast majority of users will encounter this desktop in conjunction with the Linux kernel, we are commonly referring to it as "Desktop Linux". ROX FilerThe ROX Desktop is a graphical desktop environment with ROXFiler as its file manager. Its UX is was inspired by RISC OS. ROX Filer is centered around the drag-and-drop philosophy of managing applications. To allow for this, it uses the AppDir format. Our new spec should attempt to make this format work across all file desktops, too? More information: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Application_directory GNUstep GWorkspace.appGNUstep is a Free Sotware framework that Apple's Cocoa (formerly NeXT's OpenStep) APIs but is portable to a variety of platforms and architectures. It comes with a file manager called GWorkspace.app that uses application bundles. GNUstep is available in many Linux distributions, but it has somewhat faded into abscurity, due to what I suspect is the dated 80s looking user interface (whereas Apple has constantly updated the user experience during all those decades). GWorkspace.app application bundles live in GWorkspace running on Xubuntu 16.04; on the right hand side are the same applications when viewed with today's XFCE Thunar file manager. Our new spec should attempt to make this format work across all file desktops, too? Source: Own screenshot (2018) To be investigated: Does GWorkspace.app allow for drag-and-drop application management including document binding? |

|

really nice read! thanks @probonopd hope you are well. |

|

The situation we had to solve with MacOS X was a bit different than the contemporary situation for Linux. For one thing, we had to deal with the legacy architecture introduced by the original Mac OS in 1984, chiefly the type/creator system (a set of two four-character strings that identified respectively the type of a given file and the application that created it). We also mostly had to concern ourselves with HFS, the primary Mac filesystem that could store some limited amount of metadata (bundle bit, type/creator, etc...). However, we also increasingly had to deal with other filesystems, including from Windows and Unix that did not support this, so we were in a bit of a transitional stage. Nowadays, the situation would be simpler. Dealing with multiple flavors of filesystems is a requirements, so using features that are specific to a given filesystem is out. And there's no 'legacy' architecture to worry about. You can then simplify the solution by having something that solely relies on filenames and directory structures, e.g. use the filename extension of a directory to indicate it's a bundle (no need for PkgInfo, etc...). The goal of all this was to simplify for users the task of managing and installing applications. In particular, we wanted to make it very, very, hard for a casual user to 'break' the system by inadvertently moving a file somewhere, or deleting it because they didn't know what it was for (something that happened a lot with version of Mac OS before Mac OS X). We wanted the task of installing an application to be as simple as dragging an app icon from somewhere (a server, an external drive) onto your computer's disk and be done with it. To do this, all the information that the system needed to know to handle the application was stored inside the app bundle, including its icons, its version information, the type of file it could handle, and the type of URL schemes it could handle. Then this information for 'centralized' in the Icon Services and Launch Services database. To maintain performance, applications were 'discovered' on a limited basis in a few 'well known' locations: the Applications system and user folders, and a few others, as well as automatically when the user navigated in the Finder to a directory containing an app. In practice, this worked very well. Once you had all this info, you could give users options: the ability to associate certain file types (or URL schemes) to specific applications (if more than one could handle them) either on a global/default basis or per file (you would need metadata stored with the file for this), as well as manage multiple version of applications (by default we would always use the latest known version, but a user could specify in the Open With menu another version). I'm happy to answer questions you may have about what we did back then. Like I said, some of it was done for legacy reasons that probably don't apply today, so I'd be glad to clarify. |

|

Thank you very much @arnog for taking the time to comment here. That the basic concepts are still used almost 20 years later in macOS and iOS shows that they have really passed the "test of time". Yes, I did notice that some of what was described in those WWDC sessions were workarounds to support legacy systems, and I admire the careful approach that was taken to not breaking legacy while building redundancies and robustness into the system. (The Linux desktop today would also need to take into consideration the "legacy" XDG way of doing things.)

This is precisely what the AppImage format for Linux is all about, inspired (in deep admiration) by

Thanks for your generous offer, I will attempt to keep the questions at a minimum so as to be mindful of your time, but can't thank you enough to be open to answer questions that may arise as we continue to think though this. |

|

CC @ximion this might be interesting for you as well, perhaps you want to share some thoughts? |

|

So basically a bundle is something that looks like a file (mainly in file managers, but not always) but behaves like a directory (mainly in the shell, but not always). This is not easy to get right. Perhaps a "bundle" should be a whole new kind of filesystem object; something that answers "yes" to the question "are you a file?" (for safety & backwards compatibility), but also answers "yes" to the question "are you a bundle?", allowing programs that know about bundles to be able to navigate inside it. I don't know how feasible this is, and it would probably take a long time for support to filter down into desktop environments and applications (and even longer for it to reach distributions). Another way to implement it might be to create automatic/virtual mount points in the same directories as AppImages, so if the user installs

One thing that the Mac doesn't quite get right is the fact that |

|

In terms of standardisation, it appears that Freedesktop.org is basically just a wiki and anyone can request edit access to modify specifications or create new ones. There's even a proposed Application Package Specification. Here's what the specifications page has to say about it:

According to the edit history it hasn't received much attention, so maybe you could adopt it? |

|

I was hoping that we could implement the

aspect by a thumbnailer that would write to the application database. However, turns out that GNOME now runs thumbnailers in a bubblewrap sandbox, severely restricting what they can do. https://askubuntu.com/questions/1088539/custom-thumbnailers-don-t-work-on-ubuntu-18-10-and-18-04 |

|

I don't want to derail the conversation, but I feel the need to point out that based on my experience being an Apple user since 1993, a full-time macOS user for 16 years (2000-2016) an Apple engineer for 7 years (2009 - 2016), and providing user support for an entire friends-and-family group for all of that time... Nobody knows how to install apps via drag-and-drop. While drag-and-drop app management sounds awesome in theory and has a certain conceptual elegance to it, in practice it is a usability catastrophe and has been since its inception. People who have been using Macs for decades are still capable of messing it up on a regular basis. I have seen this time and time again in the less-technical world of the humanities in academia where I've spent a lot of time. People just don't get it. The ways they mess up are varied: People run apps from inside disk images; people drag-and-drop the disk image or its volume or the zip file into the Applications folder instead of the app itself; people drag-and-drop the app onto their desktop instead of the Application folder; people forget to delete the disk image or zip file and run out of disk space (macOS apps are enormous compared to Linux apps); in short almost nobody ever does this right. The number of implementation details exposed by the drag-and-drop app installation experience is actually quite high: compressed archives; disk image containers vs volumes; filesystem structure, and so on). Easing the burden of app installation by hiding as many of these implementation details was one of the major reasons why Apple abandoned the concept for iOS and encourages the use of an App Store on macOS now. System integration is important, and various features that you point out would indeed be nice, including versioned apps, per-version app icons, transient apps on other disks, etc. But I humbly suggest that having the explicit goal of managing apps via drag-and-drop using the filesystem is a distraction. Apple tried that and it didn't actually work in practice. Even if we make a perfect system that actually does support drag-and-drop app installation to the extent that macOS does, for in the interests of usability, I would highly suggest leaving it as an experts-only feature and encouraging the use of App Store type apps instead, so that regular computer users can actually install software painlessly and properly! 😄 |

|

Thanks @Pointedstick for joining the discussion. You seem to start from the assumption that it is a good idea (and necessary) to install software, whereas I start from the assumption that installation should no longer be needed. We used to install (hardwire) networks. Today, we just switch on WLAN and "it works". This is what we need for apps. Boot a random distribution, attach a disk full of apps, and be able to run them - with no installation. This is my vision. Lately, Apple and other proprietary vendors are requiring users to register, log in, be online all the time to get apps from app stores - this is exactly the reason why I am turning my attention to the Linux Desktop (again).

Hence, unlike the Mac, for AppImage we never extract the application directory from the disk image. We leave it inside all the time. Should remove this class of user errors.

Why shouldn't they? On the Mac, you can put an app anywhere and it will work. So why not on the desktop?

Since with AppImage we never extract the application directory from the disk image, this class of user errors should also not affect us. But what I am envisioning here is not an AppImage-specific solution, but something generic enough that allows systems like AppImage, Apple .app bundles, ROX AppDirs to be hooked in (e.g., using plugins). |

You should be able to run applications without installing them, but menu and icon integrations will require some form of installation - at least it should anyway! If I have a folder full of nightly builds of my favourite application then I don't want them all to appear in the system menu. Only the ones in the dedicated

So the container format is packaging-specific but the contents (or some of the contents) are standardised? The plugin's job is to mount the container and expose the contents. The system then reads the contents and does the integration. The integration simply involves list the files in the system database: no files are moved from the package to the filesystem. |

|

One way to deal with this is to automatically "install" (i.e. register icons, menu commands, etc...) for application in well known locations, and "install" (do the same registration, potentially give the chance to the app to install drivers, etc..) apps when they are launched, regardless of their location. |

Would part of that installation process involve moving the app to the well-known location? If not, how would the sytem deal with the app being moved or removed? |

|

I fully support the goal of self-contained, drag-and-droppable apps. I just don't think that those technical features should be advertised to users and exposed as the normal method for acquiring and managing software. Again, on macOS, this is a persistent source of user confusion. Expert users should be able to take advantage of these features, sure, but regular casual users prefer central app store type solutions. Getting AppImages to integrate with them (like the Nitrux app store does) should be a primary goal IMHO. |

|

We can also learn a lot from Haiku, which seems to have solved most if not all of this:

It looks like the Haiku people share pretty much our vision of how a desktop should operate. Thanks @waddlesplash for pointing me there. |

|

That makes sense, since Haiku is inspired by BeOS, which was created by Jean-Louis Gassée, one of the original Mac guys. |

|

Turns out that GNUstep's GWorkspace file manager had figured this stuff out already decades ago: http://wiki.gnustep.org/index.php/WrapperFactory.app

Indeed the GWorkspace file manager does show application icons on It's a shame that the format is not supported by all file managers. |

Current situation

Desktop Linux, mostly through freedesktop.org specifications, currently provides only static and inflexible ways to integrate applications with the system. It is assumed that applications are installed into fixed locations into the system. The system is not really built for dynamically ever-changing per-user applications. It also assumes that every application is only present in one version.

Deficiency of the status quo: Dealing with applications that come and go on the fly

This creates challenges for situations in which applications "come and go", e.g., when an external partition (or, say an AppImage, a Snap, a file server share...) is mounted that contains applications. One has to manually copy around desktop files, icon files to locations like

$HOME/.local/icons/hicolor/with varying subdirectories that may or may not exist and be recognized depending on whether the subdirectories were already present when the desktop environment was launched, MIME files to locations like$HOME/.local/share/mime/packages, and then trigger runs of tools likeupdate-desktop-databaseandupdate-mime-database, which is a real pain:Some desktop environments then also need to update their own databases and caches, e.g., Sycoca on KDE Plasma. Whether or whether not this happens automatically and on which occasion has been a complicated mess since essentially forever.

If too many applications come and go at the same time, the system can come to a grinding halt due to the various databases and caches being updated a lot of times in short order:

Once the external partition containing applications is unmounted, one has to figure out which of the files that were previously copied around need to be deleted, and has to manually trigger various

update-....commands again.This reminds one of the state of networking before WLAN, where everything was configured statically under the assumption that there is a static networking setup that is erected when the machine is installed. Once people had mobile devices and roamed around, NetworkManager was introduced and made network management dynamic, assuming that network connections would come and go. The same has not happened on "Desktop Linux" for applictions yet, but needs to happen.

Deficiency with the status quo: Multiple versions of applications

Many applications have different icons for different versions of the same application. Firefox, for example, has constantly been evolving their icon.

The current XDG standard is entirely ignorant of this, assuming all Firefox instances on the system are sharing the same Firefox icon. macOS does a much better job because icons are stored inside each application, rather than at one central place in the filesystem.

Similarly, when a HTML file is about to be opened, then there is no clear concept which version of Firefox will get to open it under the current XDG regime.

Current workarounds in AppImage

As an AppImage-specific workaround for the inflexible, static way of how applications are integrated with the system, we have (at least) 4 different, inclomplete ways to integrate AppImages with the system (which still suffer from the shortcomings of the status quo described above but try to work around them):

appimageddaemon which needs to be installed in the system. This will watch certain directories (most notably,/Applicationsand$HOME/Applications) for AppImages, and will integrate them into the system automatically. By design, it will never move anything anywhere and will never ask the user any questions. (Compared to the Mac, this solution is not yet ideal because it does not integrate AppImages stored in random locations yet and watching the entire system with inotify would be computationally too expensive.)appimaged). It will ask the user with a popup to move every AppImage into$HOME/Applicationwhenever an AppImage is launched that is not in that location yet. (Personally I find this too intrusive as I keep my AppImage in non-standard locations but apparently some users like this.)Current workarounds in snapd

(to be written)

Current workarounds in Flatpak

(to be written)

What needs to be done

To come up with a much better (and more seamless) system than what we have now, we should

systemd. We should do this in an open discussion involving the greater Desktop Linux community, including desktop environment projects, application authors, etc.systemd(but possibly hook into them using the existing interfaces they provide as of today, such as dbus, thumbnailers, and such)The objective should be to get proper dynamic desktop integration for applications (like on the Mac) into the default installation of distributions. This pretty much excludes any solution that is AppImage-specific.

Learning from the Mac

Classic Mac OS, the various NeXT systems, and Mac OS X are still unparalleled in terms of ease-of-use when it comes to integrating applications into the system by mere drag-and-drop. It just seems to work phenomenally well, without the user having to fiddle around with desktop files, icon files, and the like.

I have written about this before.

It is about time that Desktop Linux gets the same level of usability, almost two decades later.

We have been attempting to re-create a similar level of simplicity with

appimaged, but frankly, so far we have not reached the same level of "it just works" (and performance) yet. Possibly some changes are required on deeper levels of the system and the file managers.Almost two decades ago, then Apple User Experience Architect @arnog gave insight into some of the concepts of how Mac OS X does what we would call "system integration" today in the WWDC 2000 Session 144, Application Packaging and Document Typing. The man must know, as he has been the "Architect and lead engineer of a complete rewrite of the Finder for Mac OS X", and according to his CV "Participated in weekly design meetings with Steve Jobs (and had a good time doing it)".

Applications on Mac OS X live in application directories, a subclass of what they interchangeably referred to as "bundles" and "packages" back then. Our equivalent would be AppDir. Those are often shipped inside dmg disk images, our rough equivalent of which would be AppImages.

How the system recognizes an application bundle

.app. Our equivalent would be.AppDir. It is explicitly mentioned that you are not forced to use that extension, since there is also a third optionPkgInfoin the top-level diretory of the bundle. It is explicitly mentioned that this holds type and creator information redundant what is stored elsewhere, for performance reasonsWhat triggers system integration

/Applications,/Network/Applications,/Users/$USER/Applications. Our equivalent would be to watch/Applications,$HOME/Applications, and possibly/Applicationson each newly mounted partition usinginotify. Note that the Downloads directory is not part of those. It is explicitly mentioned that while applications get integrated into the system immediately when you put them there, you can also put them into other locations where they will be picked up by the following additional measuresRegisters an application, designated by URL, in the Launch Services database.

According to (Singh, 2006) system integration is also triggered

Additionally,

LSRegisterURL(_:_:). Note that one cannot rely on applications doing this. Our equivalent would be to offer a dbus message that when called would trigger system integration.What happens when you double-click

Info.plistfile, containing, among other things, the file types the application can handle and the application version. Our equivalent would roughly be thedesktopfile amended with theX-AppImage-Versionfield. (Possibly we should settle on a YAML file that would combine what is in .desktop and AppStream metainfo files today.) The database is populated by the triggers described aboveNote that the only time the system asks the user something is when it doesn't know which application to open a file with, which rarely happens in practice, given the combination of the three triggers described above.

The database

The Launch Services registration database can be dumped like this:

(Singh, 2006)

Additional information

A year later, the concepts were covered again in WWDC 2001 Session 114, Application Packaging and Document Binding.

In Desktop Linux, we are not doing this "on the fly" yet. We should!

Bindings Database

Note that applciations also can make use of "packages", that is folders displayed as files.

The relevant Property List keys start with CFBundle (it's all defined by Core Foundation).

It gets populated by reading the

Info.plistfiles that travel inside the applications (and other types of packages). Today, one would probably use YAML or JSON instead of XML.Applications and documents have type and creator codes. The type of an application is always APPL. The creator code is what generally binds, e.g., text files which have the type TEXT (roughly equaling a MIME type) to one certain application that can handle text files (e.g., the SimpleText application). This concept seems to be missing in Desktop Linux entirely, which is why documents of the same MIME type never get opened by the application that created them, but rather by some "random" application that happens to also handle the same MIME type.

Do we need to invent/specify "MIME creators" in addition to MIME types to match what the Mac has had for a long time?

"Launch Services is the engine that does document binding." "It maintains the Bindings Database." (Not to be confused by the deprecated Classic Mac OS "DesktopDB".) On Desktop Linux, xdg-open is similar to using Launch Services to open something ("Essentially the same as double-clicking"), and mimeinfo is similar to using Launch Services to get the binding (but not quite yet!).

TODO: Check LaunchServices.h header documentation and the Launch Services TechNote.

How do you ensure that you are in the Bindings Database?

The Finder (file manager) is solely responsible for updating the Bindings Database. Whenever the user logs in, the Finder looks in some well-known places auch as the main Applications folder and the user's application folder. It scans the sub-folders as well. Other applications are added to the database when launched from the Finder.

On Desktop Linux, file managers don't do this (yet). So we have to have some other part do this job, e.g, something like appimaged in combination with thumbnailers?

Application installers can send kAFSync AppleEvent. The Desktop Linux equivalent would be to send a dbus message to appimaged.

Linux needs a bindingsd to handle

and how they work together, DYNAMICALLY ON THE FLY.

Without the collaboration of file managers, we can abuse thumbnailers to do part of the job.

How can we "properly" achieve similar results on Desktop Linux?

systemdbe a place for it? I've talked about this at https://media.ccc.de/v/ASG2018-174-2018_desktop_linux_platform_issuesSingh, A. (2006). Mac OS X Internals. Boston: Addison Wesley Professional, pp. 828-830.

Possible stakeholders

System integration for applications and "document binding" a.k.a. file association is a community-wide topic and should be addressed as such. Possible stakeholders might be:

/System/Applications. Does it work like the real deal, though?What would be a suitable forum for driving this topic community-wide?

So, on first sight it appears that freedesktop.org might be a suitable place for this kind of discussion and standardization, if we can get "non-distribution" people (like application authors and users) involved there, too.

Scope

What exactly would be the scope of "this topic"?

Somewhat related, but we should take care to keep this separate:

The text was updated successfully, but these errors were encountered: