-

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 4

A.01 Vectors

A coordinate system (or frame) is a system that uses one or more numbers (also called coordinates) to uniquely determine a position, provided that we define an origin, a unit of measurement and a positive direction. The use of a coordinate system allows problems in geometry to be translated into problems about numbers, and vice versa.

We can determine a position

For example,

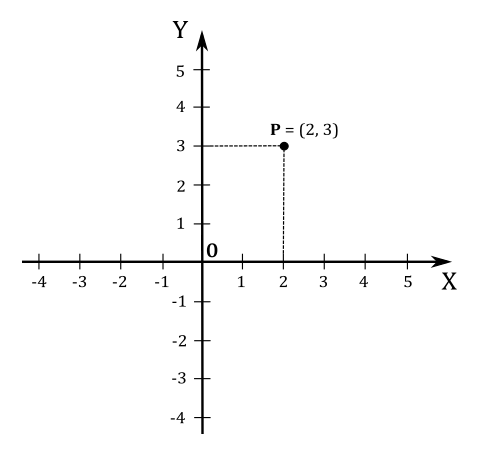

In the plane, two perpendicular lines (also called axes) are chosen, and the coordinates

For example, the point

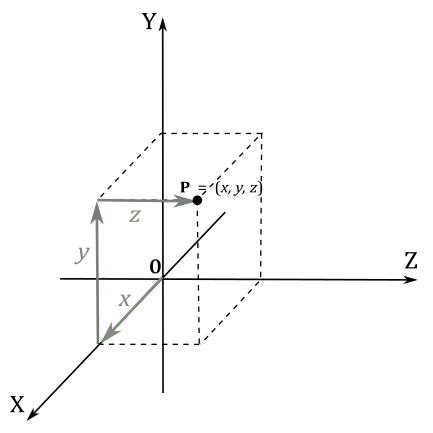

In three dimensions, three mutually orthogonal axes are chosen and the three coordinates

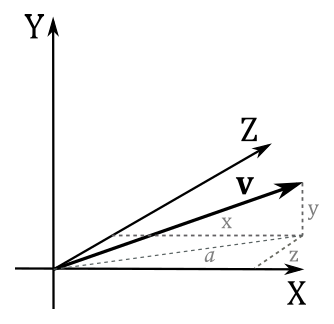

You can also see the coordinates

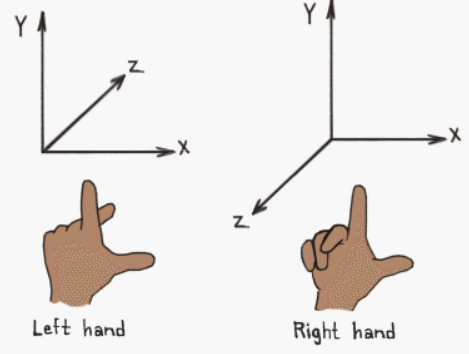

Depending on the direction and order of the axes, a three-dimensional system may be a right-handed or a left-handed system.

Usually the y-axis points up, the x-axis points right while the z-axis points forward in a left-handed coordinate system (backward in a right-handed frame). That’s not a strict rule, though. Sometimes, you can have the z-axis points up. In that case, the y-axis points backward in a left-handed system (forward in a right-handed one). You can always switch from a y-up to a z-up configuration with a simple transformation, but there's no point in providing further details here as we will mostly use a y-up configuration. Typically, with DirectX we will use a left-handed coordinate system. However, again, that’s not a strict rule: you can also use a right-handed coordinate system.

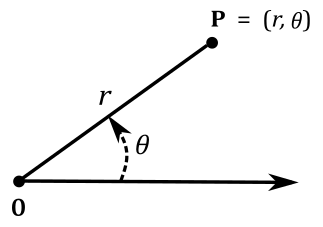

In the plane, a ray from the origin is chosen (the ray is often called polar axis, while the origin is called pole). The coordinates

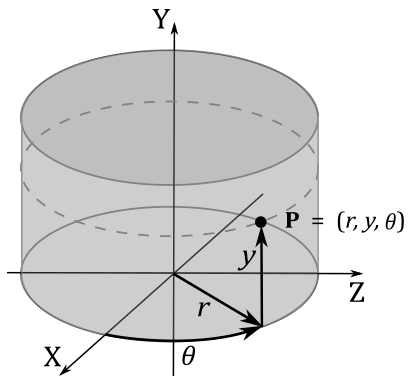

In three dimensions, with the coordinates

Spherical coordinates take this a step further by converting the pair of cylindrical coordinates

A point in the plane may be represented in homogeneous coordinates by a triple

Vectors describe quantities that have both a magnitude and a direction, such as displacements, forces and speed. In computer graphics, vectors are extensively used to specify the location of objects in the scene and the direction of their movements (as well as the direction of light rays, or the normal of surfaces). Moreover, vectors are also used to specify force and speed (especially if you are going to implement a physics engine).

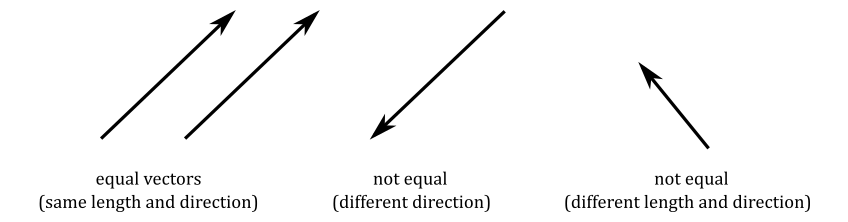

A vector can be represented geometrically by an arrow, where the length indicates the magnitude and the aim indicates the direction of the vector.

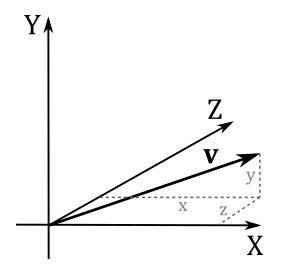

Since we need to manipulate vectors with a computer, we are not particularly interested in this geometric definition, although. Fortunately, we can also define vectors numerically with tuples (a finite sequence of numbers). To do that, we need to bind vectors to the origin of a Cartesian system (that is, you have to translate a vector without changing magnitude and direction until its tail coincides with the origin).

At that point, we can use the coordinates

When only magnitude and direction of a vector matter, then the point of application is of no importance, and the vector is called free vector. On the other hand, a vector bound to a point is called bound vector. The numerical representation of a bound vector is only valid in the system where you bind it. If you bind the same free vector to different systems, the numerical representation changes as well.

This is an important point because if you define a vector by its coordinates, those coordinates are relative to a specific frame of reference. Then, we can conclude that two vectors

We can also define some interesting operations that can be done with vectors. For example, addition, subtraction, and three different types of multiplication.

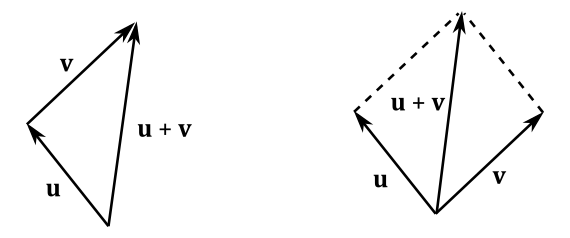

Numerically, the sum of two vector

The addition may be represented geometrically by placing the tail of the arrow

The difference of two vector

The subtraction may be represented geometrically by bounding

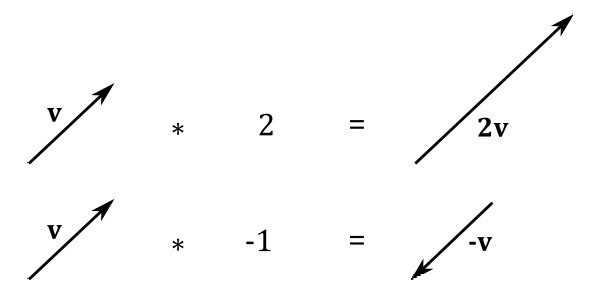

We can multiply a vector

Geometrically, this is equivalent to scale a vector (that’s why real numbers are often called scalars). If

Below are some of the properties of vector addition and scalar multiplication:

| Commutative (vector) | |

| Associative (vector) | |

| Additive Identity |

|

| Distributive (vector) | |

| Distributive (scalar) | |

| Associative (scalar) | |

| Multiplicative Identity |

|

Now we can define the length of a vector

We have that

Sometimes, only the direction of a vector is important. In that case, we can normalize the vector so as to make its length 1. Usually, the symbol

We can verify that

Three unit vectors are of particular importance:

This form of vector multiplication results in a scalar value (that’s why it’s also called scalar product). The dot product of two vector

So, the dot product of two vectors is a sum of products of the corresponding components. Below are some of the properties of the dot product:

| Commutative | |

| Distributive | |

| Square of a vector length |

The associative property doesn’t apply since

From the law of cosines

Indeed, if we set

From equation

- If

$(\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}) = 0$ then the angle$\theta$ between$\mathbf{u}$ and$\mathbf{v}$ is$90°$ (that is, they are orthogonal:$\mathbf{u}\ \bot\ \mathbf{v}$ ) - If

$(\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}) > 0$ then the angle$\theta$ between$\mathbf{u}$ and$\mathbf{v}$ is less than$90°$ - If

$(\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}) < 0$ then the angle$\theta$ between$\mathbf{u}$ and$\mathbf{v}$ is greater than$90°$

To conclude this section we will prove the law of cosines

Let

$\mathbf{a}$ be the vector from$C$ to$B$ ,$\mathbf{b}$ the vector from$C$ to$A$ , and$\mathbf{c}$ the vector from$A$ to$B$ .

We have that

$\mathbf{c}=\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b}\quad$ (subtration of two vectors)Squaring both sides and simplifying

$|\mathbf{c}|^2=|\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b}|^2$

$|\mathbf{c}|^2=(\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b})\cdot (\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b})\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad$ (square of a vector length)

$|\mathbf{c}|^2=|\mathbf{a}|^2+|\mathbf{b}|^2-2\ \mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b}\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad$ (distributive law of the dot product)

$|\mathbf{c}|^2=|\mathbf{a}|^2+|\mathbf{b}|^2-2|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}| \cos{\theta}\quad\quad\quad\quad$ (equation (1))

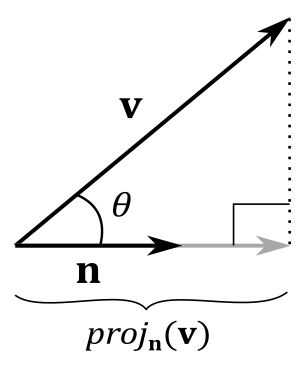

We can define the orthogonal projection of a vector

From trigonometry, we know that the adjacent side can be derived from the hypotenuse, multiplied by the cosine of the angle between adjacent side and hypotenuse. In this case, we have

with

Thanks to the orthogonal projection, we can write a generic bound vector

Indeed, we have

Also, note that

You can also see it as a sum of scaled vectors: we scale

Remember that you can also see it as a sequence of three translations: starting from the origin of the frame, we move

As stated earlier, the components of a bound vector are the coordinates of the arrowhead inside a frame. This implies we can use bound vectors to uniquely identify all the points of a frame. And indeed, we will use vectors to specify points as well. However, we still need a way to differentiate between vectors and points as they are not interchangeable. Observe that, for vectors, only direction and magnitude are important, so the point of application is irrelevant. On the other hand, points uniquely identify a location, so they only make sense if bound to the origin of a frame. Moreover, you can subtract points to get a vector that specifies how to move from a point to another. And you can also add a point and a vector to get a vector that specifies how to move a point to another location. However, unlike vectors, the addition of points doesn’t make any sense: you get the diagonal of a parallelogram, which doesn't mean anything geometrically. In short, think of vectors as free vectors, while considering points as bound vectors. So, if you have a vector

A computer cannot exactly represent all the elements in the infinite set of real numbers because it uses a finite number of bits to store values in memory. This means we have to settle for a good approximation. The downside is that, if you need to perform many calculations with approximate values, the outcome could differ significantly from the exact result. For example, a set of vectors

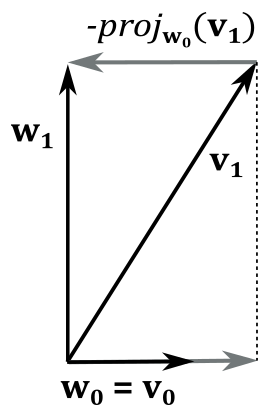

Suppose we have an un-orthonormal set of vectors

So, we have that

where

To prove that

In the 3D case, we have a third vector

Consider the following illustration. If we subtract

The last step is to normalize

This type of multiplication is also called vector product as the result is a vector (unlike the dot product which evaluates to a scalar). The cross product is defined as

A way to remember this formula is to notice that the first component of the vector

We can also use matrices to calculate the cross product. For example, the cross product

Also, the cross product can be computed multiplying a row by a matrix.

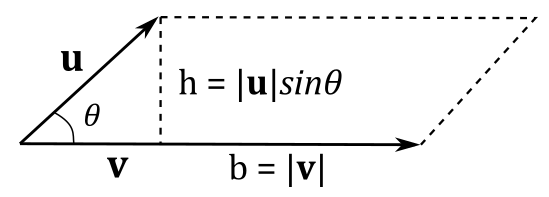

We will cover matrices in the next appendix, where we will show that the determinant of a matrix is related to the concept of hypervolume (that is, length in 1D, area in 2D, and volume in 3D). In this section we can use this information to find something interesting. We know that two vectors always lie in a plane (that is, we are in 2D), and that to calculate the area of a parallelogram we multiply its base times the height. Then, we are supposed to find a similar formula for the cross product because, to compute it, we can use the determinant of a matrix, which is related to the concept of hypervolume. Indeed, we can also write the cross product as

with

We know that

since

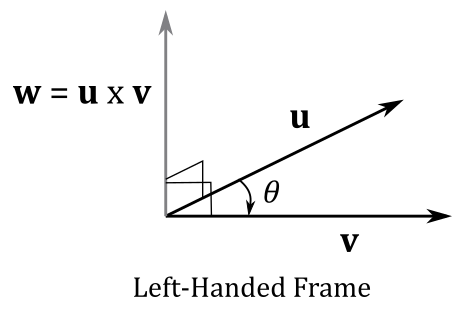

As stated above, the vector

In right-handed systems, the correct side is the one that makes

The commutative property doesn’t apply

And we also have that

A way to remember the above equivalences is to consider the unit vectors

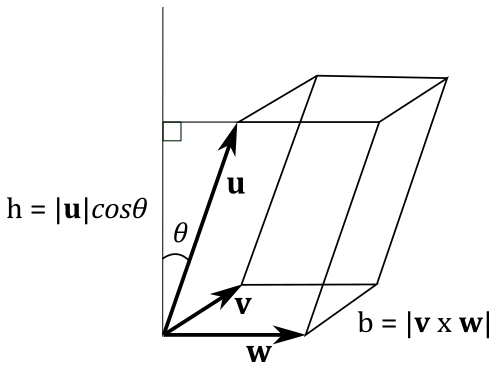

The scalar triple product is nothing really new, as it’s just a mix of the dot and cross products. It’s defined as

where

As you know, the length of the cross product is the area of a parallelogram. Also, the volume of a parallelepiped is

with

From equation

which is the scalar triple product. If you expand it you have

which is exactly the determinant of the

We conclude this section pointing out that a vector triple product

$\mathbf{a}\times (\mathbf{b}\times\mathbf{c})=(a_x, a_y, a_z)\times [(b_x, b_y, b_z)\times (c_x, c_y, c_z)]=$

$(a_x,, a_y,, a_z)\times (b_yc_z-b_zc_y,; b_zc_x-b_xc_z,; b_xc_y-b_yc_x)=$

$\big({\color{#FF6666}{a_y (b_xc_y-b_yc_x)-a_z (b_zc_x-b_xc_z)}},\ {\color{#44FF66}{a_z (b_yc_z-b_zc_y)-a_x\ (b_xc_y-b_yc_x)}},\ {\color{#44AAFF}{a_x (b_zc_x-b_xc_z)-a_y(b_yc_z-b_zc_y)}}\big)$

Below we can see that the first component of

$\mathbf{b}(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{c})-\mathbf{c}(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b})$ is equivalent to the first component of$\mathbf{a}\times(\mathbf{b}\times\mathbf{c})$

$(\mathbf{b}(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{c})-\mathbf{c}(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b}))_x = b_x (a_xc_x+a_yc_y+a_zc_z)-c_x (a_xb_x+a_yb_y+a_zb_z)=$

$a_xb_xc_x+a_yb_xc_y+a_zb_xc_z-a_xb_xc_x-a_yb_yc_x-a_zb_zc_x=$

${\color{#FF6666}{a_y (b_xc_y-b_yc_x)-a_z (b_zc_x-b_xc_z)}}$

The same applies to the other two components.

In HLSL, we simply use the built-in types float2, float3 and float4 to represent vectors of two, three and four floating-point components, respectively. Similarly, we use int2, int3 and int4 for vectors of integers. Alternatively, we can use the keyword vector to declare vectors of various components and types. The shader model defines 128-bit shader core registers to hold both integer and floating-point vectors to perform SIMD operations (more on this shortly).

To access a specific component of a vector we can use indexing, or one of two naming sets:

The position set:

The color set:

Specifying one or more vector components is called swizzling. For example:

vector<int, 1> iVector = 1; // int iVector = 1;

vector<double, 4> dVector = { 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 }; // float4 dVector = { 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 };

float4 u = { 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 0.0f };

float f0 = u.x; // f0 = 1.0f

float f1 = u.g; // f1 = 2.0f

float f2 = u[2]; // f2 = 3.0f

u.a = 4.0f; // u = (1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f)

float4 v = { 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f };

float3 vec1 = v.xyz; // vec1 = (1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f)

float2 vec2 = v.rb; // vec2 = (1.0f, 3.0f)

float4 vec3 = v.zzxy; // vec3 = (3.0f, 3.0f, 1.0f, 2.0f)

vec3.wxyz = vec3; // vec3 = (3.0f, 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f)

vec3.yw = vec1.zz; // vec3 = (3.0f, 3.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f)

float4 w = float4(vec1, 5.0); // w = (1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 5.0f)

In C++, the following definition specifies we can use the type XMVECTOR to define variables that can be mapped to 128-bit CPU registers.

typedef __m128 XMVECTOR;That is, a variable of type __m128 is backed by a memory region of 128 bits that the compiler can use as a source\destination to load\store data in\from XMM[0-7] registers, which are used in SIMD instructions. SIMD (single instruction multiple data) allows us to perform more operations with a single instruction. To better understand how SIMD works, it’s useful to consider a practical example. First, it is worth noting that in DirectX it is common to use vectors of four components, where each of them is a 4-byte floating point or integer value.

You may wonder why we have vectors of four components if we mostly work in 3D space (where only 3 coordinates are needed). Well, as we will see in a later tutorial, at some point we will introduce an extra coordinate to distinguish between free vectors and bound vectors. That is, we will work in a special homogeneous coordinate system to use both points and vectors.

Now consider the following sum of vectors, which means four sums of the corresponding components.

With SIMD we can perform the four sums in a single instruction. In general, the math API of DirectX, called DirectXMath, takes advantage of SIMD to let the CPU perform four operations (OPs) in a single instruction. That is, DirectXMath can use SIMD instructions to perform the same operation on the corresponding components of a couple of XMVECTORs used as operands\sources, as shown in the following illustration.

The only problem is that __m128 variables need to be aligned on 16-byte boundaries in memory. That’s not really an issue if you declare a global or local variable of this type because the compiler will automatically align them. Problems arise when you use a XMVECTOR (which is an alias for __m128) as a member of a structure or a class, where the C++ packing rules can misalign it. For this purpose, DirectXMath provides the following types, which allow us to use integer or floating-point vectors as class members.

// 32-bit signed floating-point components

struct XMFLOAT2

{

float x;

float y;

};

struct XMFLOAT3

{

float x;

float y;

float z;

};

struct XMFLOAT4

{

float x;

float y;

float z;

float w;

};// 32-bit signed integer components

struct XMINTT2

{

int x;

int y;

};

struct XMINT3

{

int x;

int y;

int z;

};

struct XMINT4

{

int x;

int y;

int z;

int w;

};These types can be used without worrying about alignment issues. However, we can’t take advantage of SIMD if you use them, as they don’t map to XMM registers. So, you must remember to convert to XMVECTOR before performing any calculations on vectors. DirectXMath also provides some helper functions to convert from XMFLOAT to XMVECTOR.

XMVECTOR XMLoadFloat2(const XMFLOAT2* pSource);

XMVECTOR XMLoadFloat3(const XMFLOAT3* pSource);

XMVECTOR XMLoadFloat4(const XMFLOAT4* pSource);And back from XMVECTOR to XMFLOAT (similar functions are defined for XMINT as well).

void XMStoreFloat2(XMFLOAT2* pDestination, FXMVECTOR V);

void XMStoreFloat3(XMFLOAT3* pDestination, FXMVECTOR V);

void XMStoreFloat4(XMFLOAT4* pDestination, FXMVECTOR V);If a function takes one or more XMVECTORs as parameters then:

- FXMVECTOR must be used for the first three parameters.

- GXMVECTOR must be used for the fourth parameter.

- HXMVECTOR must be used for the remaining ones.

This allows to use the appropriate calling conventions for each platform supported by the DirectXMath Library. To learn more about calling convections you can refer to the official documentation (see [3] and [4] in the reference list at the end of the tutorial).

As stated above, XMVECTOR is just an alias for __m128, which identify a type mapped to XMM registers. This means we should not use XMVECTOR to operate with vectors without using SIMD instructions. For this reason, DirectXMath provides many helper functions that take advantage of SIMD to initialize XMVECTORs and operate with them. We will examine most of these functions in the upcoming tutorials.

If you want to declare a vectorized-constant (const XMVECTOR) then it is recommended to use XMVECTORF32 for floating-point values, and XMVECTORU32 (or XMVECTORI32) for integer values. That’s because these types are defined as the union of a XMVECTOR and an array. This allows us to use the initialization syntax, and let the compiler use SIMD instructions for other operations.

__declspec(align(16)) struct XMVECTORF32

{

union

{

float f[4];

XMVECTOR v;

};

inline operator XMVECTOR() const { return v; }

inline operator const float* () const { return f; }

};

static const XMVECTORF32 vZero = { 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f };[1] Practical Linear Algebra: A Geometry Toolbox (Farin, Hansford)

[2] Library Internals (Microsoft Docs)

[3] __vectorcall (Microsoft Docs)

If you found the content of this tutorial somewhat useful or interesting, please consider supporting this project by clicking on the Sponsor button. Whether a small tip, a one time donation, or a recurring payment, it's all welcome! Thank you!