We implemented a simulation of realistic spatial sound on the HoloLens, an augmented reality headset, that considers the topology of the environment when calculating reverberations. The only hardware on the HoloLens that is available to developers is a small Intel Atom CPU with 4 cores. We used Unity and C# to interface with the HoloLens and broke down the virtual space into subsections that could be calculated independently of each other, and achieved parallelism using a combination of multithreading and SIMD. To simulate the movement of sound waves around the room, we used a modified ray tracing algorithm to create a virtual sound field in the environment.

Video: https://youtu.be/TppSbkVxA1w

The Microsoft HoloLens utilizes spatial audio to create the illusion that sounds are coming from specific places in the augmented reality environment. However, the HoloLens does not consider any properties of the room during audio processing. The size and shape of a room can significantly influence sound, and taking these parameters into consideration can improve immersion in an augmented reality environment.

Our plan is to develop a parallel ray tracing algorithm on the HoloLens GPU, and use it to trace sounds in the augmented reality environment in real time. The HoloLens is already capable of detecting walls in the room by detecting planes, and we will use this information to model size and shape of the room the user is currently in.

Ray tracing clearly lends itself to parallelism because the calculations for each ray are independent. Each ray bounces off a surface in the room, and a new ray is created from this and so on, so the behavior of a ray is recursive and limited only by setting a maximum recursion depth. Because we would be doing the same calculation on each ray, we can exploit data parallelism. By processing each ray to some max recursive depth, we can compute which direction each ray points to relative to the user’s head, and group rays with similar directions together, scaling each ray for volume. We can then calculate the contribution to the overall sound from each ray grouping in parallel.

We performed a raycasting of soundwaves to create realistic reverberation and spatial sound that can run in real time on the Microsoft HoloLens while maintaining 60 frames per second. The HoloLens calculates a spatial map of the space it is in as well as the position of the user relative to the space. We modeled how sound travels in a room similarly to how light reflects off objects, which is a close approximation to how sound will travel in the room when a large number of rays are spawned, despite light being a ray and sound being a wave. Each sound source spawns many rays travelling in random directions around the room which ricochet off the walls, and the sound dampens every time the sound ray bounces off the wall. When a ray passes by the user’s head, the sound plays.

The most compute-intensive operation is going through all the rays and checking which enter the user’s earshot. Rays are independent of each other, and so the raycasts can be computed entirely in parallel. However, the small core count available on the HoloLens’ Intel Atom CPU make it difficult to compute rays at 60fps. In addition to this, we must also account for the fact that the user’s head is constantly changing position, and that the HoloLens updates the mesh of the space roughly once per second, which affects how sound should be reverberating in the room.

Parallelizing tasks on a HoloLens in Unity/C# is complicated on its own because the Unity API is not thread safe. Therefore, we could not use any Unity data structures or Library functions outside of the main thread. This meant that we had be strategic about how and when we access the HoloLens APIs. The HoloLens does support parallelism, but only using the Microsoft Universal Windows Platform (UWP) threading library, which was introduced in the .NET 4.0 framework. Unity only supports .NET 3.5 and earlier, making the build from Unity incompatible with the HoloLens.

Our raytracing algorithm was specifically geared to run optimally on the Microsoft HoloLens. We used Unity and C# so we could take advantage of Microsoft’s low level APIs for interacting with the spatial map of the room and using the HoloLens’ ASICs. For parallelism, we used Unity’s Mono.Simd library and C#’s native System.Threading.Tasks library.

To approach the problem, we divided the augmented reality space into a custom data structure we called Quadrants. Each quadrant was responsible for keeping track of the spatial mapping data relevant to that section of the room and the rays that intersect it. When the HoloLens grabs more spatial mapping data, which can be represented as Add, Remove, or Change; we asynchronously request the new information regarding the mesh and send it to the relevant Quadrant. That way, we keep most Quadrants free and ready to do work if they are needed. The mesh data is stored in a dictionary with unique identifiers for each of the mesh objects, so if a mesh object is deleted or updated, we can easily remove the old piece of the mesh and replace it with the updated mapping.

When a new sound source is spawned, we use Unity’s Physics.Raycast to spawn 75 rays originating from the source and getting back where the sound rays collide with the walls of the room. On every collision, we spawn a new sound ray reflecting off the object it collided with and dampen the associated volume by a factor of 0.8. We allow this to continue up to our maximum recursion depth, which is set to 30 reflections. We then cache the results, since these will stay the same unless the mesh gets updated in a location that is relevant to the ray. This means that at steady state (once all the sound sources are placed and the room has been scanned), we won’t need to do any additional computation surrounding how the sound rays are created.

Whenever a ray crosses through a Quadrant, we add it to the Quadrant’s list of active rays. On every frame, we check what Quadrant the user is in and loop through its active rays to compute which rays come close enough to be heard. This eliminates the majority of the rays from the loop. When a sound has completed playing or time has elapsed past its source's endpoint, it is no longer active, so we can remove it from the Quadrant and destroy the ray.

Since Unity itself is not thread-safe, we could not use any Unity data structures or library functions anywhere but the main thread. To get around this, we created a rayData class that contains the relevant information about each ray that we calculated when we spawned the sound sources. We wrote our own version of Unity's Bounds.Intersect() function to calculation intersections between rays and Quadrants, and utilized the Mono.Simd library, which supports 4-byte wide vector operations, to parallelize the intersection checks across the different quadrants for each ray. We also implemented our own thread-safe collision detection method, which is used to calculate which rays should be heard. To work around the problem of incompatible .NET frameworks, we had to put in compiler guards of to micromanage what parts of the code should be compiled by Unity and what parts should be ignored until it is compiled in Microsoft Visual Studio.

The computation done by our raytracing algorithm occurred in two places: on the creation of a new sound object, and in the user position update function. Therefore, when measuring performance, we put timing markers at the beginning and end of these sections to calculate the time spent in each. Since our goal was to maintain a framerate of 60fps, our main goal was to limit the latency of user update function. Our goal was to limit the audio processing time to 2ms, leaving enough time in each 16.67ms frame for other computational tasks. For benchmarking and demoing, we implemented a gesture recognizer in Unity that allowed the user to place sound objects in their environment with a tap. We performed tests with 10 sound sources running at once, each emitting 75 rays with a maximum depth of 30. We did separate tests for both long (25 second) and short (5 second) sound sources. The hardware for all tests was the 4 core Intel Atom processor on the HoloLens.

The above graph represents the latency of initializing and raytracing a single sound source at various stages of our implementation. Note that we did not split up results between short and long clips, as the actual length of the clip does not influence this section of the algorithm. The baseline implementation was a sequential raytracer made using Unity’s built in Physics.Raycast() function. The quadrants bar shows the speed-up from our custom room-sectioning data structure, which only considers rays that pass through the quadrant the user is occupying. The final bar shows the latency obtained from replacing Unity’s built in intersection detection function with our own implementation. Our implementation parallelizes the computation, utilizing the Mono.Simd library to perform 4-byte wide vector calculations to determine the intersections for each ray. Our best latency for computing a single source is a bit high at 3.5ms, limiting the number of audio sources we can initialize in one frame to 4. However, since this method is only called when a new audio source is created it, it does not significantly affect the overall framerate.

The second graph shows the amount of time spent processing the user's position in the space and determining what sounds should be played. Since this function is being consistently called each frame, this is where the majority of execution is spent. The baseline implementation loops through all the rays and detects collisions with the user using the built-in Physics.Raycast function. The second set of bars represents the improvement from processing only the rays intersecting the user’s quadrant, and from deleting rays that are no longer audible. Finally, the multithreading bars represent the speedup obtained from replacing Unity’s Physics.Raycast function with our own thread-safe implementation that made multithreading across 4 threads possible. Using the multithreaded approach, we were able to achieve a latency of about 1.1ms per frame, which outperforms our target latency by 50%.

In the user update graph, there is a large difference between the performance on long and shorter sources. When using longer sound clips, there is a lot more overlap of ray sounds, which takes up a larger amount of the CPU’s resources for audio processing. The multithreaded implementation allows for collision detection calculations to be performed off the main thread, so they are not affected by the strain of audio processing. For shorter clips, there is less overlap in the rays so the benefits of multithreading are minimal.

The main limit to our speedup was our reliance on the Unity API. To access the mesh data on the HoloLens, we needed to use Unity built in functions, which are not thread safe. Because of this we were unable to parallelize our code by simply treating each raytrace as an independent event, since the rays are interacting with the mesh which can only be done on the main thread. Starting audio could also only be done on the main thread, forcing us to preprocess collisions in parallel and then sequentially start sound each update frame. Furthermore, the Mono.Simd library, which is the only SIMD library that Unity supports, utilizes at most 4-byte wide vector instructions, while the Intel Atom on the Hololens has 12 execution contexts. We could have benefited from being able to use all 12 these execution contexts when calculating the intersections of rays with quadrants, as the data parallelism of the intersection calculations could have benefited from up to 16 execution contexts, one for each quadrant.

Raytracing algorithms naturally lend themselves to parallelization, but due to limitations in the Unity and HoloLens APIs the trivial multi-threading solution is not viable for collision detection. To efficiently simulate room reverberations on the HoloLens, we utilized data parallel approaches such as SIMD and a custom Quadrants data structure to circumvent the main thread of the Unity API. Additionally, we were able to achieve four concurrent threads on the Atom CPU by implementing our own thread-safe raycasting method. Our implementation can simulate 10 simultaneous audio sources at 60fps making it viable for games with smaller sound libraries. Further investigation needs to be done to evaluate the performance of raytracing outside of the Unity environment.

Intel Geometric Sound Propogation

Currently, the Microsoft HoloLens utilizes spatial audio to create the illusion that sounds are coming from particular places in the augmented reality environment. However, the HoloLens does not take into account any properties of the room during audio processing. The size and shape of a room can significantly influence sound, and taking these parameters into consideration can improve imersion in an augmented reality environment.

Our plan is to develop a parallel ray tracing algorithm on the HoloLens GPU, and use it to trace sounds in the augmented reality environment in real time. The HoloLens is already capable of detecting walls in the room by detecting planes, and we will use this information to model size and shape of the room the user is currently in.

Ray tracing clearly lends itself to parallelism because the calculations for each ray are independent. Each ray bounces off a surface in the room, and a new ray is created from this and so on, so the behavior of a ray is recursive and limited only by setting a maximum recursion depth. Because we would be doing the same calculation on each ray, we can exploit data parallelism. By processing each ray to some max recursive depth, we can compute which direction each ray points to relative to the users head, and group rays with similar directions together, scaling each ray for volume. We can then calculate the contribution to the overall sound from each ray grouping in parallel.

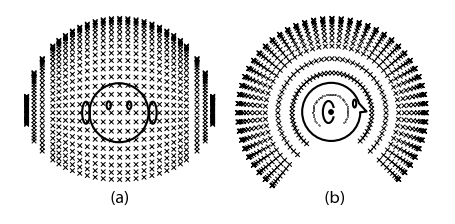

All possible directions affecting the user. Each ray contributes to a number of these directions. (Image from mattmontag.com)