With the introduction of Combine and SwiftUI, we will face some transition periods in our code base. Our applications will use both Combine and a third-party reactive framework, or both UIKit and SwiftUI, which makes it potentially difficult to guarantee a consistent architecture over time.

Spin is a tool to build feedback loops within a Swift based application allowing you to use a unified syntax whatever the underlying reactive programming framework and whatever Apple UI technology you use (RxSwift, ReactiveSwift, Combine and UIKit, AppKit, SwiftUI).

Please dig into the Demo applications if you already feel comfortable with the feedback loop theory.

Summary:

- Change Log

- About State machines

- About Spin

- The multiple ways to build a Spin

- The multiple ways to create a Feedback

- Feedback lifecycle

- Feedbacks and scheduling

- What about dependencies in Feedbacks

- Using Spin in a UIKit or AppKit based app

- Using Spin in a SwiftUI based app

- Using Spin with multiple Reactive Frameworks

- How to make spins talk together

- Demo applications

- Installation

- Acknowledgements

Please read the CHANGELOG.md for information about evolutions and breaking changes.

What is a State Machine?

It's an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The state machine can change from one state to another in response to some external inputs. The change from one state to another is called a transition. A state machine is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the conditions for each transition

Guess what! An application IS a state machine.

We just have to find the right tool to implement it. This is where feedback loops come into play 👍.

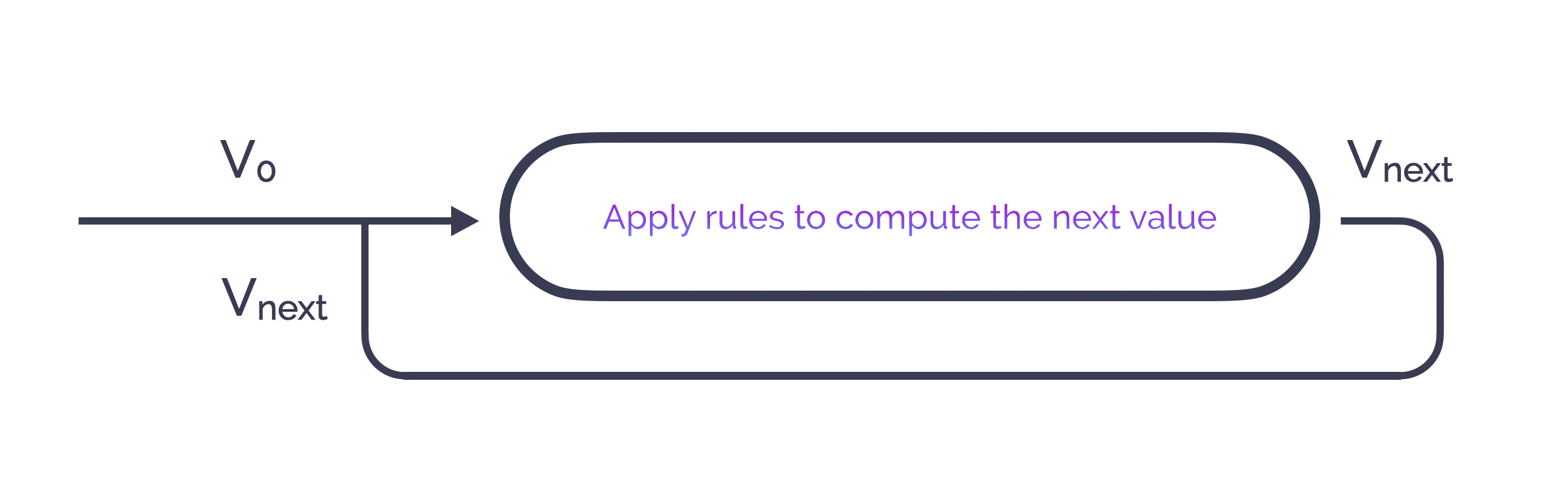

A Feedback Loop is a system that is able to self-regulate by using the resulting value from its computations as the next input to itself, constantly adjusting this value according to given rules (Feedback Loops are used in domains like electronics to automatically adjust the level of a signal for instance).

Stated this way might sound obscur and unrelated to software engineering, BUT “adjusting a value according to certain rules” is exactly what a program, and by extension an application, is made for! An application is the sum of all kinds of states that we want to regulate to provide a consistent behaviour following precise rules.

Feedback loops are perfect candidates to host and manage state machines inside an application.

Spin is a tool whose only purpose is to help you build feedback loops called "Spins". A Spin is based on three components: an initial state, several feedbacks, and a reducer. To illustrate each one of them, we will rely on a basic example: a “feedback loop / Spin” that counts from 0 to 10.

- The initial state: this is the starting value of our counter, 0.

- A feedback: this is the rule we apply to the counter to accomplish our purpose. If 0 <= counter < 10 then we ask to increase the counter else we ask to stop it.

- A reducer: this is the state machine of our Spin. It describes all the possible transitions of our counter given its previous value and the request computed by the feedback. For instance: if the previous value was 0 and the request is to increase it, then the new value is 1, if the previous was 1 and the request is to increase it, then the new value is 2, and so on and so on. When the request from the feedback is to stop, then the previous value is returned as the new value.

Feedbacks are the only place where you can perform side effects (networking, local I/O, UI rendering, whatever you do that accesses or mutates a state outside the local scope of the loop). Conversely, a reducer is a pure function that can only produce a new value given a previous one and a transition request. Performing side effects in reducers is forbidden, as it would compromise its reproducibility.

In real life applications, you can obviously have several feedbacks per Spin in order to separate concerns. Each of the feedbacks will be applied sequentially on the input value.

Spin offers two ways to build a feedback loop. Both are equivalent and picking one depends only on your preference.

Let’s try them by building a Spin that regulates two integer values to make them converge to their average value (like some kind of system that would adjust a left and a right channel volume on stereo speakers to make them converge to the same level).

The following example will rely on RxSwift, here are the ReactiveSwift and Combine counterparts; you will see how similar they are.

We will need a data type for our state:

struct Levels {

let left: Int

let right: Int

}We will also need a data type to describe the transitions to perform on Levels:

enum Event {

case increaseLeft

case decreaseLeft

case increaseRight

case decreaseRight

}Now we can write the two feedbacks that will have an effect on each level:

func leftEffect(inputLevels: Levels) -> Observable<Event> {

// this is the stop condition to our Spin

guard inputLevels.left != inputLevels.right else { return .empty() }

// this is the regulation for the left level

if inputLevels.left < inputLevels.right {

return .just(.increaseLeft)

} else {

return .just(.decreaseLeft)

}

}

func rightEffect(inputLevels: Levels) -> Observable<Event> {

// this is the stop condition to our Spin

guard inputLevels.left != inputLevels.right else { return .empty() }

// this is the regulation for the right level

if inputLevels.right < inputLevels.left {

return .just(.increaseRight)

} else {

return .just(.decreaseRight)

}

}And finally to describe the state machine ruling the transitions, we need a reducer:

func levelsReducer(currentLevels: Levels, event: Event) -> Levels {

guard currentLevels.left != currentLevels.right else { return currentLevels }

switch event {

case .decreaseLeft:

return Levels(left: currentLevels.left-1, right: currentLevels.right)

case .increaseLeft:

return Levels(left: currentLevels.left+1, right: currentLevels.right)

case .decreaseRight:

return Levels(left: currentLevels.left, right: currentLevels.right-1)

case .increaseRight:

return Levels(left: currentLevels.left, right: currentLevels.right+1)

}

}In that case, the “Spinner” class is your entry point.

let levelsSpin = Spinner

.initialState(Levels(left: 10, right: 20))

.feedback(Feedback(effect: leftEffect))

.feedback(Feedback(effect: rightEffect))

.reducer(Reducer(levelsReducer))That’s it. The feedback loop is built. What now?

If you want to start it, then you have to subscribe to the underlying reactive stream. To that end, a new operator “.stream(from:)” has been added to Observable in order to connect things together and provide an Observable you can subscribe to:

Observable

.stream(from: levelsSpin)

.subscribe()

.disposed(by: self.disposeBag)There is a shortcut function to directly subscribe to the underlying stream:

Observable

.start(spin: levelsSpin)

.disposed(by: self.disposeBag)For instance, the same Spin using Combine would be (considering the effects return AnyPublishers):

let levelsSpin = Spinner

.initialState(Levels(left: 10, right: 20))

.feedback(Feedback(effect: leftEffect))

.feedback(Feedback(effect: rightEffect))

.reducer(Reducer(levelsReducer))

AnyPublisher

.stream(from: levelsSpin)

.sink(receiveCompletion: { _ in }, receiveValue: { _ in })

.store(in: &cancellables)

or

AnyPublisher

.start(spin: levelsSpin)

.store(in: &cancellables)In this case we use a "DSL like" syntax thanks to Swift 5.1 function builder:

let levelsSpin = Spin(initialState: Levels(left: 10, right: 20)) {

Feedback(effect: leftEffect)

Feedback(effect: rightEffect)

Reducer(levelsReducer)

}Again, with Combine, same syntax considering that effects return AnyPublishers:

let levelsSpin = Spin(initialState: Levels(left: 10, right: 20)) {

Feedback(effect: leftEffect)

Feedback(effect: rightEffect)

Reducer(levelsReducer)

}The way to start the Spin remains unchanged.

As you saw, a “Feedback loop / Spin” is created from several feedbacks. A feedback is a wrapper structure around a side effect function. Basically, a side effect has this signature (Stream<State>) -> Stream<Event>, Stream being a reactive stream (Observable, SignalProducer or AnyPublisher).

As it might not always be easy to directly manipulate Streams, Spin comes with a bunch of helper constructors for feedbacks allowing to:

- directly receive a State instead of a Stream (like in the example with the

Levels) - filter the input State by providing a predicate:

RxFeedback(effect: leftEffect, filteredBy: { $0.left > 0 }) - extract a substate from the State by providing a lens or a keypath:

RxFeedback(effect: leftEffect, lensingOn: \.left)

Please refer to FeedbackDefinition+Default.swift for completeness.

There are typical cases where a side effect consist of an asynchronous operation (like a network call). What happens if the very same side effect is called repeatedly, not waiting for the previous ones to end? Are the operations stacked? Are they cancelled when a new one is performed?

Well, it depends 😁. By default, Spin will cancel the previous operation. But there is a way to override this behaviour. Every feedback constructor that takes a State as a parameter can also be passed an ExecutionStrategy:

- .cancelOnNewState, to cancel the previous operation when a new state is to be handled

- .continueOnNewState, to let the previous operation naturally end when a new state is to be handled

Choose wisely the option that fits your needs. Not cancelling previous operations could lead to inconsistency in your state if the reducer is not protected against unordered events.

Reactive programming is often associated with asynchronous execution. Even though every reactive framework comes with its own GCD abstraction, it is always about stating which scheduler the side effect should be executed on.

By default, a Spin will be executed on a background thread created by the framework.

However, Spin provides a way to specify a scheduler for the Spin it-self and for each feedback you add to it:

Spinner

.initialState(Levels(left: 10, right: 20), executeOn: MainScheduler.instance)

.feedback(Feedback(effect: leftEffect, on: SerialDispatchQueueScheduler(qos: .userInitiated)))

.feedback(Feedback(effect: rightEffect, on: SerialDispatchQueueScheduler(qos: .userInitiated)))

.reducer(Reducer(levelsReducer))or

Spin(initialState: Levels(left: 10, right: 20), executeOn: MainScheduler.instance) {

Feedback(effect: leftEffect)

.execute(on: SerialDispatchQueueScheduler(qos: .userInitiated))

Feedback(effect: rightEffect)

.execute(on: SerialDispatchQueueScheduler(qos: .userInitiated))

Reducer(levelsReducer)

}Of course, it remains possible to handle the Schedulers by yourself inside the feedback functions.

As we saw, a Feedback is a wrapper around a side effect. Side effects, by definition, will need some dependencies to perform their work. Things like: a network service, some persistence tools, a cryptographic utility and so on.

However, the side effect signature doesn't allow to pass dependencies, only a state. How can we take those deps into account ?

These are three possible technics:

class MyUseCase {

private let networkService: NetworkService

private let cryptographicTool: CryptographicTool

init(networkService: NetworkService, cryptographicTool: CryptographicTool) {

self.networkService = networkService

self.cryptographicTool = cryptographicTool

}

func load(state: MyState) -> AnyPublisher<MyEvent, Never> {

guard state == .loading else return { Empty().eraseToAnyPublisher() }

// use the deps here

self.networkService

.fetch()

.map { [cryptographicTool] in cryptographicTool.decrypt($0) }

...

}

}

// then we can build a Feedback with this UseCase

let myUseCase = MyUseCase(networkService: MyNetworkService(), cryptographicTool: MyCryptographicTool())

let feedback = Feedback(effect: myUseCase.load)This technic has the benefit to be very familiar in terms of conception and could be compatible with existing patterns in your application.

It has the downside of forcing us to be careful while capturing dependencies in the side effect.

In the previous technic, we use the MyUseCase only as a container of dependencies. It has no other usage than that. We can get rid of it by using a function (global or static) that will receive our dependencies and help capture them in the side effect:

typealias LoadEffect: (MyState) -> AnyPublisher<MyEvent, Never>

func makeLoadEffect(networkService: NetworkService, cryptographicTool: CryptographicTool) -> LoadEffect {

return { state in

guard state == .loading else return { Empty().eraseToAnyPublisher() }

networkService

.fetch()

.map { cryptographicTool.decrypt($0) }

...

}

}

// then we can build a Feedback using this factory function

let effect = makeLoadEffect(networkService: MyNetworkService(), cryptographicTool: MyCryptographicTool())

let feedback = Feedback(effect: effect)Spin comes with some Feedback initializers that ease the injection of dependencies. Under the hood, it uses a generic technic derived from the above one.

func loadEffect(networkService: NetworkService,

cryptographicTool: CryptographicTool,

state: MyState) -> AnyPublisher<MyEvent, Never> {

guard state == .loading else return { Empty().eraseToAnyPublisher() }

networkService

.fetch()

.map

}

// then we can build a Feedback directly using the appropriate initializer

let feedback = Feedback(effect: effect, dep1: MyNetworkService(), dep2: MyCryptographicTool())Among those 3 technics it is the less verbose one. It feels a little bit like magic but simply uses partialization under the hood.

Although a feedback loop can exist by itself without any visualization, it makes more sense in our developer world to use it as a way to produce a State that we be rendered on screen and to handle events emitted by the users.

Fortunately, taking a State as an input for rendering and returning a stream of events from the user interactions looks A LOT like the definition of a feedback (State -> Stream<Event>), we know how to handle feedbacks 😁, with a Spin of course.

As the view is a function of a State, rendering it will change the states of the UI elements. It is a mutation exceeding the local scope of the loop: UI is indeed a side effect. We just need a proper way to incorporate it in the definition of a Spin.

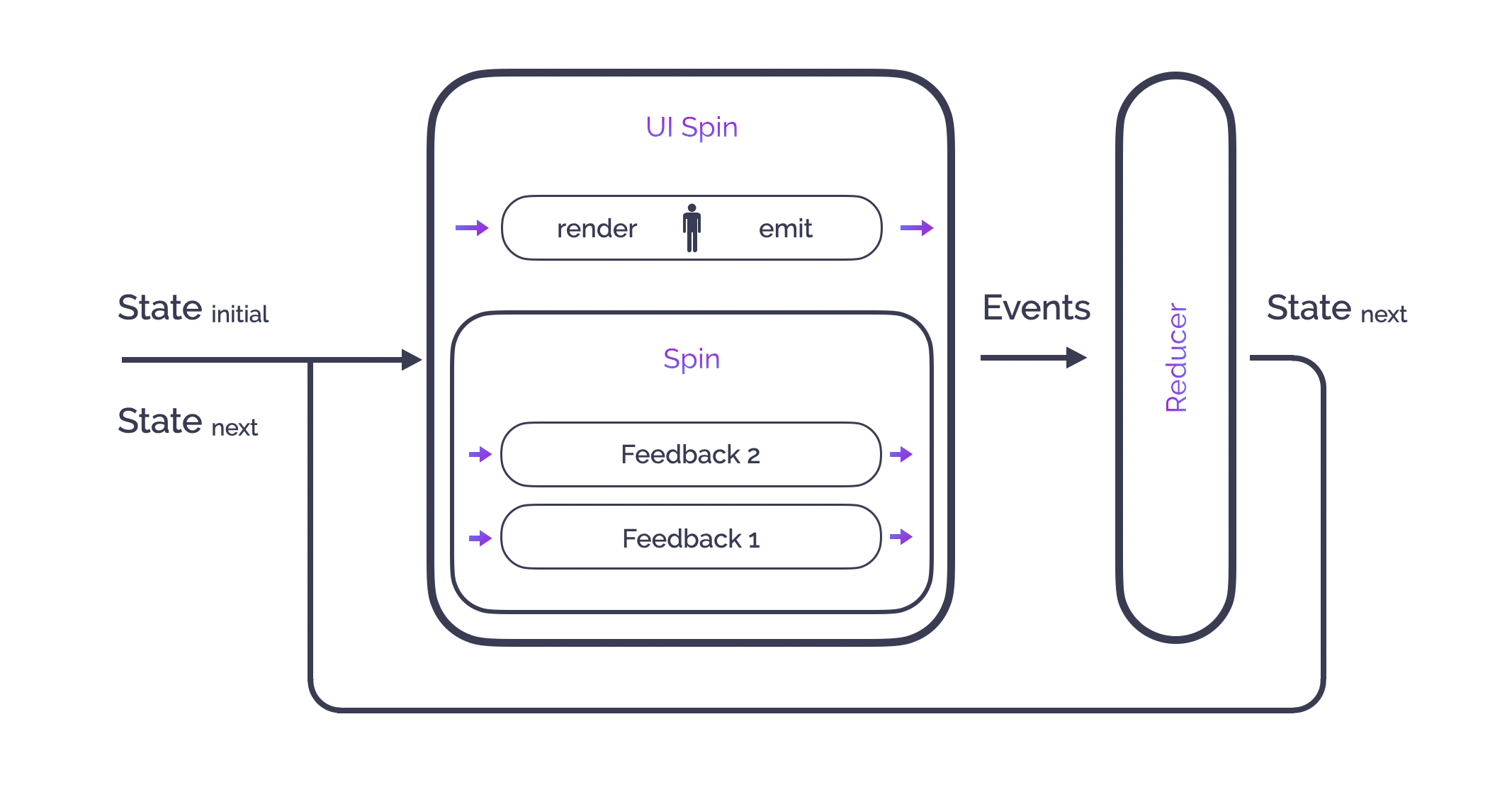

Once a Spin is built, we can “decorate” it with a new feedback dedicated to the UI rendering/interactions. A special type of Spin exists to perform that decoration: UISpin.

As a global picture, we can illustrate a feedback loop in the context of a UI with this diagram:

In a ViewController, let’s say you have a rendering function like:

func render(state: State) {

switch state {

case .increasing(let value):

self.counterLabel.text = "\(value)"

self.counterLabel.textColor = .green

case .decreasing(let value):

self.counterLabel.text = "\(value)"

self.counterLabel.textColor = .red

}

}We need to decorate the “business” Spin with a UISpin instance variable of the ViewController so their lifecycle is bound:

// previously defined or injected: counterSpin is the Spin that handles our counter business

self.uiSpin = UISpin(spin: counterSpin)

// self.uiSpin is now able to handle UI side effects

// we now want to attach the UI Spin to the rendering function of the ViewController:

self.uiSpin.render(on: self, using: { $0.render(state:) })And once the view is ready (in “viewDidLoad” function for instance) let’s start the loop:

Observable

.start(spin: self.uiSpin)

.disposed(by: self.disposeBag)or a shortest version:

self.uiSpin.start()

// the underlying reactive stream will be disposed once the uiSpin will be deinitSending events in the loop is very straightforward; simply use the emit function:

self.uiSpin.emit(Event.startCounter)Because SwiftUI relies on the idea of a binding between a State and a View and takes care of the rendering, the way to connect the SwiftUI Spin is slightly different, and even simpler.

In your view you have to annotate the SwiftUI Spin variable with “@ObservedObject” (a SwiftUISpin being an “ObservableObject”):

@ObservedObject

private var uiSpin: SwiftUISpin<State, Event> = {

// previously defined or injected: counterSpin is the Spin that handles our counter business

let spin = SwiftUISpin(spin: counterSpin)

spin.start()

return spin

}()you can then use the “uiSpin.state” property inside the view to display data and uiSpin.emit() to send events:

Button(action: {

self.uiSpin.emit(Event.startCounter)

}) {

Text("\(self.uiSpin.state.isCounterPaused ? "Start": "Stop")")

}A SwiftUISpin can also be used to produce SwiftUI bindings:

Toggle(isOn: self.uiSpin.binding(for: \.isPaused, event: .toggle) {

Text("toggle")

}\.isPaused is a keypath which designates a sub state of the state, and .toggle is the event to emit when the toggle is changed.

As stated in the introduction, Spin aims to ease the cohabitation between several reactive frameworks inside your apps to allow a smoother transition. As a result, you may have to differentiate a RxSwift Feedback from a Combine Feedback since they share the same type name, which is Feedback. The same goes for Reducer, Spin, UISpin and SwiftUISpin.

The Spin frameworks (SpinRxSwift, SpinReactiveSwift and SpinCombine) come with typealiases to differentiate their inner types.

For instance RxFeedback is a typealias for SpinRxSwift.Feedback, CombineFeedback is the one for SpinCombine.Feedback.

By using those typealiases, it is safe to use all the Spin flavors inside the same source file.

All the Demo applications use the three reactive frameworks at the same time. But the advanced demo application is the most interesting one since it uses those frameworks in the same source files (for dependency injection) and take advantage of the provided typealiases.

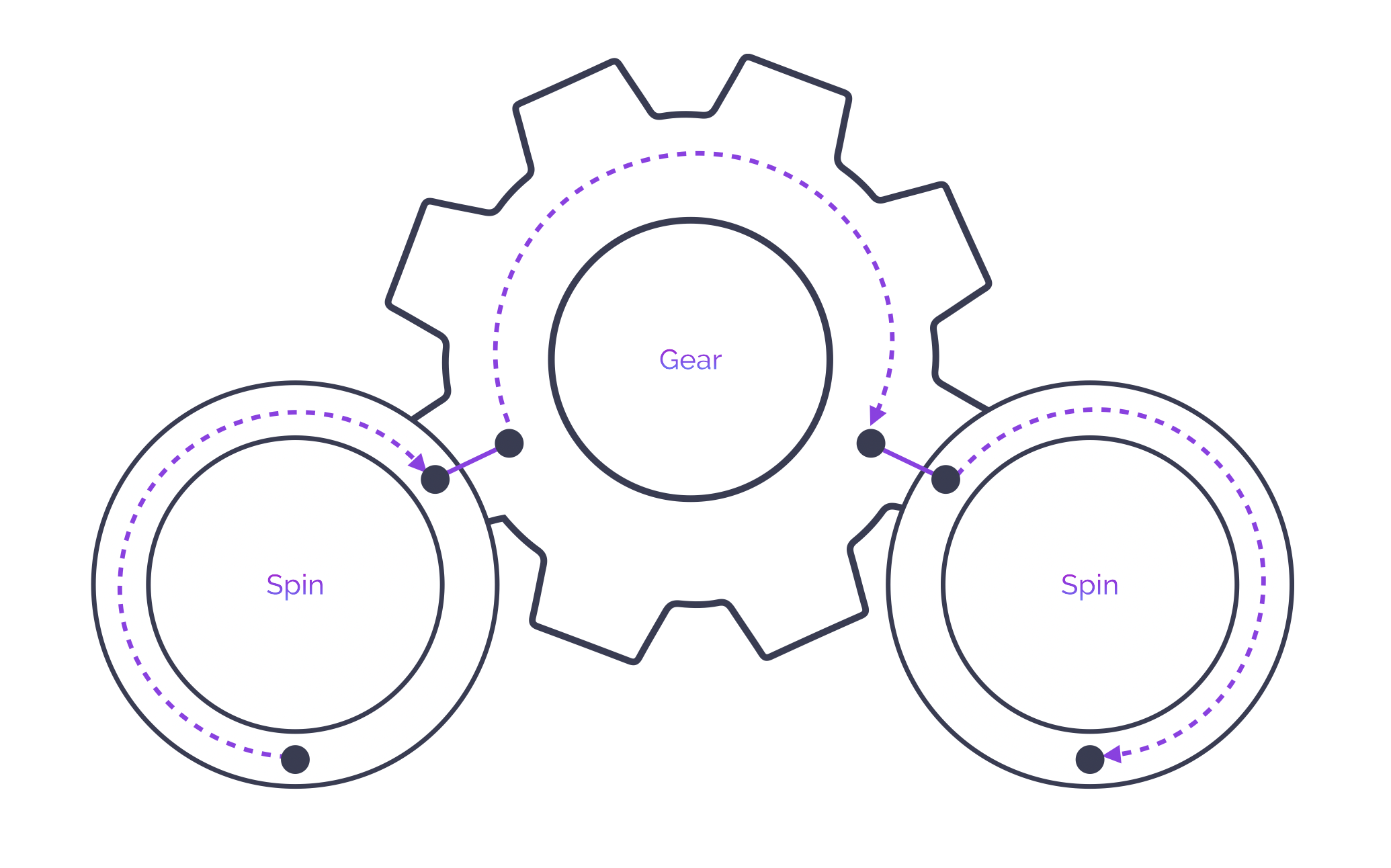

There are some use cases where two (or more) feedback loops have to talk together directly, without involving existing side effects (like the UI for instance).

A typical use case would be when you have a feedback loop that handles the routing of your application and checks for the user's authentication state when the app starts. If the user is authorized then the home screen is presented, otherwise a login screen is presented. Assuredly, once authorized, the user will use features that fetch data from a backend and as a consequence that can lead to authorization issues. In that case you'd like the loops that drive those features to communicate with the routing one in order to trigger a new authorization state checking.

In design patterns, this kind of need is fulfilled thanks to a Mediator. This is a transversale object used as a communication bus between independent systems.

In Spin, the mediator equivalent is called a Gear. A Gear can be attached to several feedbacks, allowing them to push and receive events.

How to attach Feedbacks to a Gear so it can push/receive events from it ?

First thing first, a Gear must be created:

// A Gear has its own event type:

enum GearEvent {

case authorizationIssueHappened

}

let gear = Gear<GearEvent>()We have to tell a feedback from the check authorization Spin how to react to events happening in the Gear:

let feedback = Feedback<State, Event>(attachedTo: gear, propagating: { (event: GearEvent) in

if event == .authorizationIssueHappened {

// the feedback will emit an event only in case of .authorizationIssueHappened

return .checkAuthorization

}

return nil

})

// or with the short syntax

let feedback = Feedback<State, Event>(attachedTo: gear, catching: .authorizationIssueHappened, emitting: .checkAuthorization)

...

// then, create the Check Authorization Spin with this feedback

...At last we have to tell a feedback from the feature Spin how it will push events in the Gear:

let feedback = Feedback<State, Event>(attachedTo: gear, propagating: { (state: State) in

if state == .unauthorized {

// only the .unauthorized state should trigger en event in the Gear

return .authorizationIssueHappened

}

return nil

})

// or with the short syntax

let feedback = Feedback<State, Event>(attachedTo: gear, catching: .unauthorized, propagating: .authorizationIssueHappened)

...

// then, create the Feature Spin with this feedback

...This is what will happen when the feature spin is in state .unauthorized:

FeatureSpin: state = .unauthorized

↓

Gear: propagate event = .authorizationIssueHappened

↓

AuthorizationSpin: event = .checkAuthorization

↓

AuthorizationSpin: state = authorized/unauthorized

Of course in this case, the Gear must be shared between the two Spins. You might have to make it a Singleton depending on your use case.

In the Spinners organization, you can find 2 demo applications demonstrating the usage of Spin with RxSwift, ReactiveSwift, and Combine.

- A basic counter application: UIKit version and SwiftUI version

- A more advanced “network based” application using dependency injection and a coordinator pattern (UIKit): UIKit version and SwiftUI version

Add this URL to your dependencies:

https://github.com/Spinners/Spin.Swift.git

Add the following entry to your Cartfile:

github "Spinners/Spin.Swift" ~> 0.20.0

and then:

carthage update Spin.Swift

Add the following dependencies to your Podfile:

pod 'SpinReactiveSwift', '~> 0.20.0'

pod 'SpinCombine', '~> 0.20.0'

pod 'SpinRxSwift', '~> 0.20.0'

You should then be able to import SpinCommon (base implementation), SpinRxSwift, SpinReactiveSwift or SpinCombine

The advanced demo applications use Alamofire for their network stack, Swinject for dependency injection, Reusable for view instantiation (UIKit version) and RxFlow for the coordinator pattern (UIKit version).

The following repos were also a source of inspiration: