-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 21

UsingPure

Using the Pure interpreter is quite easy. Once the interpreter is installed, you're ready to go. You can invoke the interpreter from the command line as follows. (There are a number of other ways to run Pure if you're not a CLI fan, see below.)

$ pure

The interpreter prints its sign-on message and leaves you at its > prompt:

__ \ | | __| _ \ Pure 0.59 (x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu)

| | | | | __/ Copyright (c) 2008-2014 by Albert Graef

.__/ \__,_|_| \___| (Type 'help' for help, 'help copying'

_| for license information.)

Loaded prelude from /usr/local/lib/pure/prelude.pure.

>

The interpreter has built-in support for double precision floating point numbers, integers (both 32 bit machine ints and bigints; the latter are denoted with a trailing L symbol), strings and lists, so you can start using it as a sophisticated kind of desktop calculator right away:

> 17/12+23;

24.4166666666667

> pow 2 100;

1267650600228229401496703205376L

> "Hello, "+"world!";

"Hello, world!"

> [1,2,3]+[4,5,6];

[1,2,3,4,5,6]

> 1..10;

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

> 0:2..10;

[0,2,4,6,8,10]

Each expression to be evaluated must be terminated with a semicolon. You can also store intermediate results in variables:

> let x = 17/12; x+23;

24.4166666666667

> let x = 1..10; x!5; x!!(3..6);

6

[4,5,6,7]

(Note that ! and !! are Pure's indexing and slicing operations. These are all defined in the standard prelude. You can find a brief overview of some common operations here.)

New functions can be defined just as easily. For instance, here's the Fibonacci function (this is a really inefficient implementation, but it does the job for smaller values of n, and is good enough for illustration purposes):

> fib n = if n<=1 then n else fib (n-2) + fib (n-1);

> map fib (0..10);

[0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34,55]

(You may notice a slight delay when your function is executed for the first time. Nothing to worry about, it's just the JIT compiler kicking in, which compiles the function "just in time" to native code when it is first called.)

By default, Pure definitions are as polymorphic as it gets, so the above definition will work just as well with other types of numbers, e.g.:

> map fib (0.0..10.0);

[0.0,1.0,1.0,2.0,3.0,5.0,8.0,13.0,21.0,34.0,55.0]

> map fib (0L..10L);

[0L,1L,1L,2L,3L,5L,8L,13L,21L,34L,55L]

The show command provides a quick means to check what we have accomplished so far:

> show

fib n = if n<=1 then n else fib (n-2)+fib (n-1);

let x = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10];

It's also possible to just dump our definitions to a file, so that we can edit them in a text editor and reload them with the interpreter later:

> dump -n fib.pure

> !cat fib.pure

// dump written Sat Apr 4 05:59:05 2009

fib n = if n<=1 then n else fib (n-2)+fib (n-1);

let x = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10];

(In interactive mode, ! at the beginning of a line is the usual shell escape, so the second command above invokes the system's cat command to print the contents of the script file we just saved. This is handy if we want to check what's been written, because the dump command itself doesn't provide any feedback.)

At this point you might want to explore some of the other modules in the standard library. These can be imported with a using declaration. E.g., to do more serious math stuff, Pure provides the math.pure module:

> using math;

> map sin (-pi/2:-pi/4..pi/2);

[-1.0,-0.707106781186547,0.0,0.707106781186547,1.0]

(Besides the usual mathematical functions, math.pure also provides Pure's incarnations of complex and rational numbers.)

If you want to do some I/O, you'll need the system.pure module:

> using system;

> puts "Hello, world!";

Hello, world!

14

Yes, that's indeed the C puts function being called there. Pure makes it very easy to call C functions, you only have to tell the interpreter about the prototype of the function (in some cases you'll also have to load a shared library with a using declaration, see the manual for details). Just for fun, let's compute some random values using the rand function from the C library:

> extern int rand();

> [rand|i=1..5];

[1025202362,1350490027,783368690,1102520059,2044897763]

That's a simple example of a list comprehension at work there. List comprehensions let you create a list through "generator" and "filter" clauses, in the same way that sets are usually denoted in mathematics. In addition, Pure also provides Octave-style matrices as an alternative way of representing aggregate values, which is more efficient for many numerical applications. Matrix comprehensions can be used to construct matrices with ease. For instance:

> eye n = {i==j|i=1..n;j=1..n};

> eye 3;

{1,0,0;0,1,0;0,0,1}

Well, we barely scratched the surface here, but I guess that this should be enough to get you started, so that you can begin exploring Pure on your own. You can find more examples on the Examples page. Please also have a look at the Rewriting page which explains in more detail how function definitions work in Pure, and at the Addons page which lists the addon libraries available for doing practical programming with GUIs, graphics, databases, etc.

To exit the interpreter, just type the quit command at the beginning of a line (on Unix systems, typing the end-of-file character Ctrl-D will do the same).

> quit

When running interactively, the interpreter also offers a symbolic debugging facility. To make this work, you have to invoke the interpreter with the -g option:

$ pure -g

(This will make your program run much slower, so this option should only be used if you actually need the debugger.)

In the interpreter you then just set breakpoints on the functions you want to debug, using the break command. For instance, here is a sample session where we employ the debugger to single-step through an evaluation of the factorial:

> fact n::int = if n>0 then n*fact (n-1) else 1;

> break fact

> fact 1;

** [1] fact: fact n::int = if n>0 then n*fact (n-1) else 1;

n = 1

(Type 'h' for help.)

:

** [2] fact: fact n::int = if n>0 then n*fact (n-1) else 1;

n = 0

:

++ [2] fact: fact n::int = if n>0 then n*fact (n-1) else 1;

n = 0

--> 1

** [2] (*): x::int*y::int = x*y;

x = 1; y = 1

:

++ [2] (*): x::int*y::int = x*y;

x = 1; y = 1

--> 1

++ [1] fact: fact n::int = if n>0 then n*fact (n-1) else 1;

n = 1

--> 1

1

Lines beginning with ** indicate that the evaluation was interrupted to show the rule which is currently being considered, along with the current depth of the call stack, the invoked function and the values of parameters and other local variables in the current lexical environment. The prefix ++ denotes reductions which were actually performed during the evaluation and the results that were returned by the function call (printed as --> return value).

In the above example we just kept hitting the carriage return key to walk through the evaluation step by step. But at the debugger prompt : you can also enter various special debugger commands, e.g., to print and navigate the call stack, step over the current call, or continue the evaluation unattended until you hit another breakpoint. If you know other source level debuggers like gdb then you should feel right at home.

More information about the debugger can be found in the Pure Manual.

Of course you can also run your scripts directly from the command line, as follows:

$ pure myscript.pure

This executes the script in batch mode. Add the -i option if you prefer to run the script in interactive mode:

$ pure -i myscript.pure

It is possible to pass command line parameters to the script (these are available in Pure by means of the predefined argv variable, see the manual for details):

$ pure myscript.pure foo bar baz

On Unix systems, you can run Pure scripts as standalone programs, by making the script executable and adding a "shebang" like the following at the beginning of the script:

#!/usr/local/bin/pure

The interpreter can also create native executables which can be run from the shell without a hosting interpreter. For instance:

$ pure -c myscript.pure -o myscript

$ ./myscript

This considerably reduces startup times and lets you deploy Pure programs on systems without an installation of the Pure interpreter (the runtime library is still needed, though). Please refer to the Pure Manual for details.

A number of other command line options are available; try pure -h for a list of those.

When running interactively, the Pure interpreter usually employs the GNU readline library to provide some useful command line editing facilities. The cursor up and down keys can then be used to walk through the command history, existing commands can be edited and resubmitted with the Return key, etc. The command history is saved in the .pure_history file in your home directory between different invocations of the interpreter. Moreover, Pure's pure-readline module provides an interface to the readline library so that you can use it in your Pure programs, too.

Please note that this feature is only available if the interpreter was built with readline support (which is the default if it's available). You can also disable readline support on the command line, by invoking the interpreter with the --noediting option. This might be useful in situations where readline doesn't work properly. (In particular, it has been found that on MS Windows, readline lacks support for AltGr key combinations on international keyboards.)

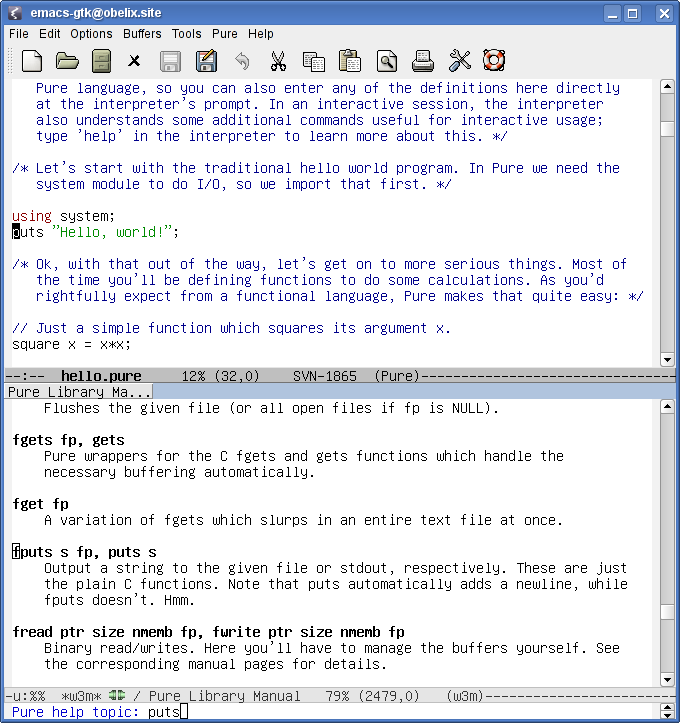

If you're friends with GNU Emacs then the Emacs Pure mode distributed with the Pure sources is probably the most convenient way to run Pure for you. Here's a screenshot showing Emacs with Pure mode in action:

Normally, the required pure-mode elisp files should be installed automatically in your emacs/site-lisp directory if Emacs is detected at configure time. You then still have to add the following lines to your .emacs startup file:

(require 'pure-mode)

(setq auto-mode-alist (cons '("\\.pure$" . pure-mode) auto-mode-alist))

(add-hook 'pure-mode-hook 'turn-on-font-lock)

(add-hook 'pure-eval-mode-hook 'turn-on-font-lock)

To get the most out of the integrated online help (C-c C-h in Pure mode), we recommend installing emacs-w3m and enabling it in your .emacs as follows:

(require 'w3m-load)

More customization options are described at the beginning of the pure-mode.el file. Once you have set things up to your liking you can invoke Emacs with your Pure script as follows:

$ emacs fib.pure

To run the script now just type Ctrl-C Ctrl-K. This will open a **pure-eval** window in Emacs in which you can execute Pure interpreter commands as usual. This has the added benefit that you can get a transcript of your interpreter session simply by saving the contents of the **pure-eval** buffer in a file. Emacs Pure mode offers many other useful features which turn it into a useful IDE for Pure programming. Try Ctrl-H M in a Pure buffer to read the online documentation of the mode for more details.

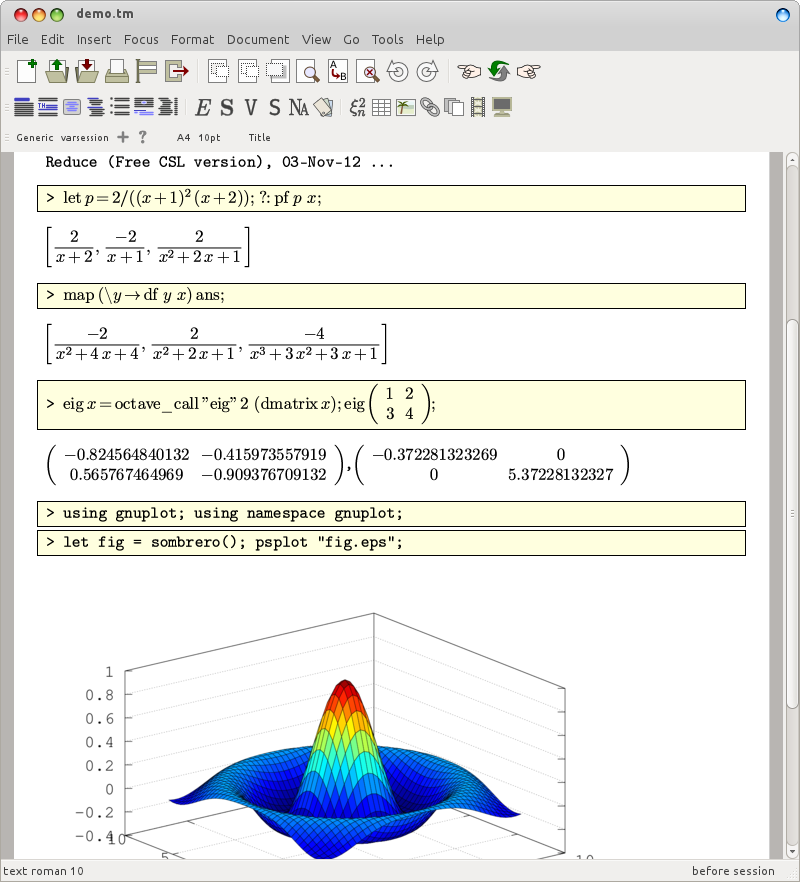

As of Pure 0.56, it's also possible to run Pure as a plugin in GNU TeXmacs, the free scientific editor. This is especially useful if you also have the Pure Octave and Reduce modules installed, which equip Pure with numeric and symbolic computing capabilities as well as plotting and mathematical typesetting functionality. Math input and output are both supported, so that you can make your Pure scripts and the printed results look like real mathematical formulas. Please check the TeXmacs wiki page for more details.

The Pure TeXmacs plugin is included in the Pure base package; information on how to get this plugin up and running can be found in the installation instructions. Here's a TeXmacs screenshot showing a Pure session with Reduce, Octave and Gnuplot:

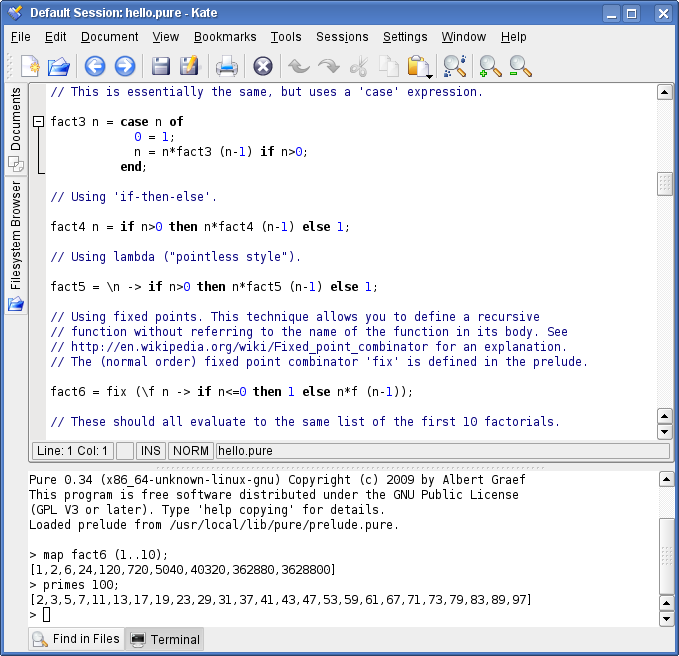

Syntax highlighting support is available for a number of other popular text editors, such as Vim, Gedit and Kate. The Kate support is particularly nice because it also provides code folding for comments and block structure. See the etc directory in the sources. Installation instructions are contained in the language files. Here's a screenshot showing Kate with a Pure script loaded:

asitdepends has implemented a Pure mode for jEdit, which provides syntax highlighting and completion for keywords.

Adam Sanderson has created a TextMate bundle for Pure, which provides syntax highlighting, some useful completions, and documentation look up in MacroMates' TextMate editor for OSX. Other supported OSX editors are BBEdit and TextWrangler; a corresponding syntax highlighting file by Hoigaard/autotelicum is available in the main Pure package.

Adam's TextMate bundle has also been ported over to Sublime Text which has gained much popularity recently and is available for all major platforms (Linux, Mac OSX and Windows). This port is named Sublime Pure and is available in its own repository on Bitbucket. It doesn't offer some of the more advanced features of the TextMate bundle yet, but adds support for the Sublime Text build system and snippets, and has been updated to the latest Pure syntax.