cdnupload uploads your website’s static files to a CDN with a content-based hash in the filenames, giving great caching while avoiding versioning issues. cdnupload is:

- Fast and simple to integrate

- Helps you follow web best practices: use a CDN, good Cache-Control headers, versioned filenames

- Works with web apps written in any language

- Written in Python (runs on Python 2 and 3)

The tool helps you follow performance best practices by including a content-based hash in each asset filename.

Deploying is really fast too: only files that have actually changed will be uploaded (with a new hash).

cdnupload is trivial to install:

$ pip install cdnupload

It's simple to use:

$ cdnupload /website/static s3://static-bucket --key-map=statics.json uploading script.js to script_8f3283c6342816f7.js uploading style.css to style_abcdef0123456789.css writing key map JSON to statics.json

And it's easy to integrate in most languages, for example Python:

import json, settings

def init_server():

with open('statics.json') as f:

settings.statics = json.load(f)

def static_url(path):

return '//mycdn.com/' + settings.statics[path]

cdnupload is a Python package which runs under Python 3.5+ as well as Python 2.7. To install it from PyPI as a command-line script and in the global Python environment, simply type:

pip install cdnupload

If you are using a specific version of Python or want to install it in a virtual Python environment, activate the virtual environment first, then run the pip install.

Additionally, if you’ll be using Amazon S3 as a destination, you’ll need to install the boto3 package to interact with Amazon AWS. To install boto3, type the following (in your virtual environment if you’re using one):

pip install boto3

After cdnupload is installed, you can run the command-line script simply by typing cdnupload. Or, if you need to run it against a specific Python interpreter, run the script as a module with python -m, like so:

/path/to/my/python -m cdnupload

cdnupload is primarily a command-line tool that uploads your site’s static files to a CDN (well, really the CDN’s origin server). It optionally generates a JSON “key mapping” that maps file paths to destination keys. A destination key is a file path with a hash in it based on the file’s contents. This allows you to set up the CDN to cache your static files aggressively, with an essentially infinite expiry time (max age).

(For a brief introduction to what a CDN is and why you might want to use one, see the CDN section of this document.)

When you upload statics, you specify a source directory and a destination directory (or Amazon S3 URL or other origin pseudo-URL). For example, you can upload all the static files from the /website/static directory to static-bucket, and output the key mapping to the file statics.json using the following command:

cdnupload /website/static s3://static-bucket --key-map=statics.json

The uploader will walk the source directory tree, query the destination S3 bucket (or directory), and upload any files that are missing. For example, if you have one JavaScript file and two CSS files, the output of the tool might look something like this:

uploading script.js to script_0beec7b5ea3f0fdb.js uploading style.css to style_62cdb7020ff920e5.css uploading mobile.css to mobile_bbe960a25ea311d2.css writing key map JSON to statics.json

If you modify mobile.css and then run it again, you’ll see that it only uploads the changed files:

uploading mobile.css to mobile_6b369e490de120a9.css writing key map JSON to statics.json

It doesn’t delete unused files on the destination directory automatically (as the currently-deployed website is probably still using them). To do that, you need to use the delete action:

cdnupload /website/static s3://static-bucket --action=delete

Here’s what the output might be after the above uploads:

deleting mobile_bbe960a25ea311d2.css

There are many command-line options to control what files to upload, change the destination parameters, etc. And you can use the Python API directly if you need advanced features or if you need to add another destination “provider”.

You’ll also need to integrate with your web server so that your web application knows the hash mapping and can output the correct static URLs. That can be as simple as a static_url template function that uses the key map JSON to convert from a file path to the destination key. See details in the web server integration section below.

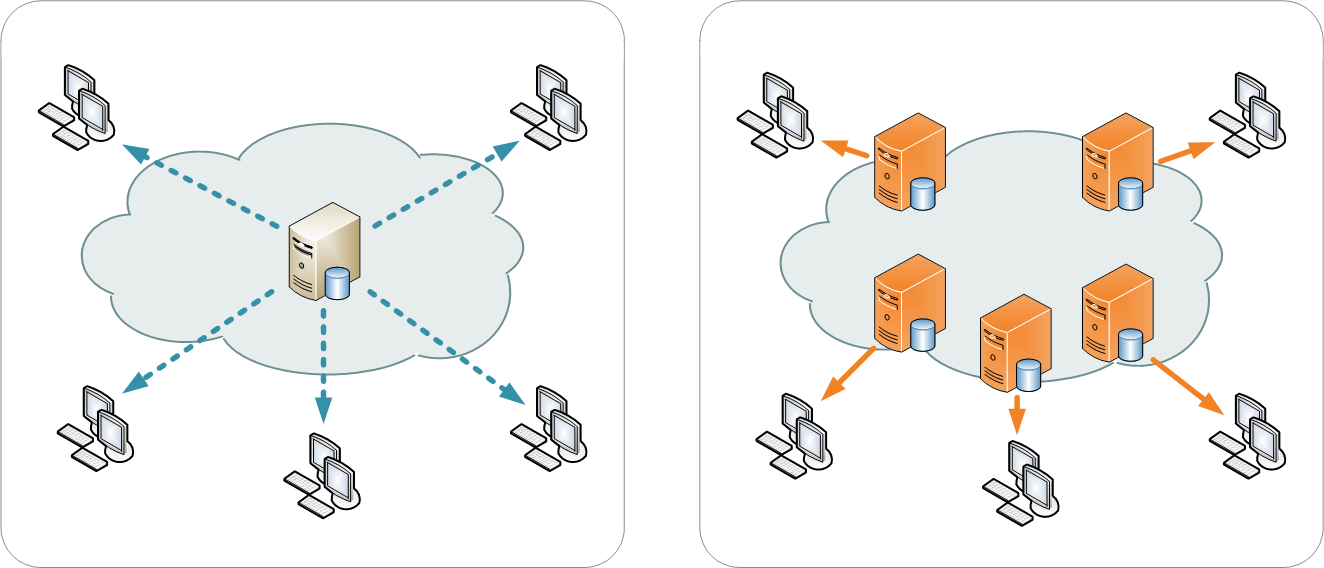

If you’re not sure what a CDN is, or if you’re wondering why you should use one, this section is for you.

CDN stands for Content Delivery Network, which is a service that serves your static files -- heavily cached, on servers around the world that are close to your users.

So if someone from New Jersey requests https://mycdn.com/style.css, the CDN will almost certainly have a cached version in an East Coast or even a local New Jersey data center, and will serve that up to the user faster than you can say “HTTP/2”.

If the CDN doesn’t have a cached version of the file, it will in turn request it from the origin server (where the files are hosted). If you’re using something like Amazon S3 as your origin server, that request will be quick too, and the user will still get the file in good time. From then on, the CDN will serve the cached version.

Because the files are heavily cached (ideally with long expiry times), you need to include version numbers in the filenames. cdnupload does this by appending to the filename a 16-character hash based on the file’s contents. For example, style.css might become style_abcdef0123456789.css, and then style_a0b1c2d3e4f56789.css in the next revision.

On one website we run, we saw our static file load time drop from 1500ms to 220ms when we starting using cdnupload with the Amazon Cloudfront CDN.

So you should use a CDN if your site gets a good amount of traffic, and you need good performance from various locations around the world. You probably don’t need to use a CDN if you have a small personal site.

Using the Amazon CloudFront CDN together with Amazon S3 as an origin server is a great place to start -- like other AWS products, you only pay for the bytes you use, and there’s no monthly fee.

The format of the cdnupload command line is:

cdnupload [options] source destination [dest_args]

Where options are short or long command line options (-s or --long). You can mix these freely with the positional arguments if you want.

source is the source directory of your static files, for example /website/static. Use the optional --include and --exclude arguments, and other arguments described below, to control exactly which files are uploaded.

destination is the destination directory to upload to, or an s3://static-bucket/prefix path for uploading to Amazon S3.

You can also specify a custom scheme for the destination (the scheme:// part of the URL), and cdnupload will try to import a module named cdnupload_scheme (which must be on the PYTHONPATH) and use that module’s Destination class along with the dest_args to create the destination instance.

For example, if you create your own uploader for Google Cloud Storage, you might use the prefix gcs:// and name your module cdnupload_gcs. Then you could use gcs://my/path as a destination, and cdnupload would instantiate the destination instance using cdnupload_gcs.Destination('gcs://bucket', **dest_args).

See the custom destination section for more details about custom Destination subclasses.

dest_args are destination-specific arguments passed as keyword arguments to the Destination class (for example, for s3:// destinations, useful dest args might be max-age=86400 or region-name=us-west-2). Note that hyphens in dest args are converted to underscores, so region-name=us-west-2 becomes region_name='us-west-2'.

For help on destination-specific args, use the dest-help action. For example, to show S3-specific destination args:

cdnupload source s3:// --action=dest-help

-h, --help Show help about these command-line options and exit. -a ACTION, --action ACTION Specify action to perform (the default is to upload):

upload: Upload files from the source to the destination (but only if they’re not already on the destination).delete: Delete unused files at the destination (files no longer present at the source). Be careful with deleting, and use--dry-runto test first!dest-help: Show help and available destination arguments for the given Destination class.-d, --dry-run Show what the script would upload or delete instead of actually doing it. This option is recommended before running with --action=delete, to ensure you’re not deleting more than you expect.-e PATTERN, --exclude PATTERN Exclude source files if their relative path matches the given pattern (according to globbing rules as per Python’s

fnmatch). For example,*.txtto exclude all text files, or__pycache__/*to exclude everything under the pycache directory. This option may be specified multiple times to exclude more than one pattern.Excludes take precedence over includes, so you can do

--include=*.txtbut then exclude a specific text file with--exclude=docs/README.txt.-f, --force If uploading, force all files to be uploaded even if destination files already exist (useful, for example, when updating headers on Amazon S3).

If deleting, allow the delete to occur even if all files on the destination would be deleted (the default is to prevent that to avoid

rm -rfstyle mistakes).-i PATTERN, --include PATTERN If specified, only include source files if their relative path matches the given pattern (according to globbing rules as per Python’s

fnmatch). For example,*.pngto include all PNG images, orimages/*to include everything under the images directory. This option may be specified multiple times to include more than one pattern.Excludes take precedence over includes, so you can do

--include=*.txtbut then exclude a specific text file with--exclude=docs/README.txt.-k FILENAME, --key-map FILENAME Write key mapping to given file as JSON (but only after successful upload or delete). This file can be used by your web server to produce full CDN URLs for your static files.

Keys in the JSON object are the original paths (relative to the source root), and values in the object are the destination paths (relative to the destination root). For example, the JSON might look like

{"script.js": "script_0beec7b5ea3f0fdb.js", ...}.-l LEVEL, --log-level LEVEL Set the verbosity of the log output. The level must be one of:

debug: Most detailed output. Log even files that the script would skip uploading.verbose: Verbose output. Log when the script starts, finishes, and when uploads and deletes occur (or would occur if doing a--dry-run).default: Default level of log output. Only log when and if the script actually uploads or deletes files (no start or finish logs). If there’s nothing to do, don’t log anything.error: Only log errors.off: Turn all logging off completely.-v, --version Show cdnupload’s version number and exit.

--continue-on-errors Continue after upload or delete errors. The script will still log the errors, and it will also return a nonzero exit code if there is at least one error. The default is to stop on the first error. --dot-names Include source files and directories that start with .(dot). The default is to skip any files or directories that start with a dot.--follow-symlinks Follow symbolic links to directories when walking the source tree. The default is to skip any symbolic links to directories. --hash-length N Set the number of hexadecimal characters of the content hash to use for destination key. The default is 16. --ignore-walk-errors Ignore errors when walking the source tree (for example, permissions errors on a directory), except for an error when listing the source root directory.

In addition to using the command line script to upload files, you’ll need to modify your web server so it knows how to generate the static URLs including the content-based hash in the filename.

The recommended way to do this is to use the key mapping JSON, which is written out by the --key-map command line argument when you upload your statics. You can load this into a key-value dictionary when your server starts up, and then generate a static URL simply by looking up the relative path of a static file in this dictionary.

Even though the keys in the JSON are relative file paths, they’re normalized to always use / (forward slash) as the directory separator, even on Windows. This is so consumers of the mapping can look up files directly in the mapping with a consistent path separator.

Below is a simple example of loading the key mapping in your web server startup (call init_server() on startup) and then defining a function to generate full static URLs for use in your HTML templates. This example is written in Python, but you can use any language that can parse JSON and look something up in a map:

import json

import settings

def init_server():

settings.cdn_base_url = 'https://mycdn.com/'

with open('statics.json') as f:

settings.statics = json.load(f)

def static_url(rel_path):

"""Convert relative static path to full static URL (including hash)"""

return settings.cdn_base_url + settings.statics[rel_path]

And then in your HTML templates, just reference a static file using the static_url function (referenced here as a Jinja2 template filter):

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{{ 'style.css'|static_url }}">

If your web server is in fact written in Python, you can also import cdnupload directly and use cdnupload.FileSource with the same parameters as the upload command line. This will build the key mapping at server startup time, and may simplify the deployment process a little:

import cdnupload

import settings

def init_server():

settings.cdn_base_url = 'https://mycdn.com/'

source = cdnupload.FileSource(settings.static_dir)

settings.static_paths = source.build_key_map()

If you have huge numbers of static files, this is not recommended, as it does have to re-hash all the files when the server starts up. So for larger sites it’s best to produce the key map JSON and copy that to your app servers as part of your deployment process.

If you reference static files in your CSS (for example, background images with url(...) expressions), you’ll need to either remove them from your CSS and generate them in an inline <style> section at the top of your HTML, or use a post-processor script on your CSS to change the URLs from relative to full hashed URLs.

For small sites, it may be simpler to just extract them from your CSS. For example, for a CSS rule like this:

body.home {

font-family: Verdana;

font-size: 10px;

background-image: url(/static/images/hero.jpg);

}

You would remove just the background-image line and put it in an inline style block in the <head> section of relevant pages, like this:

<head>

<!-- other head elements; link to the stylesheet above -->

<style type="text/css">

body.home {

background-image: url({{ 'images/hero.jpg'|static_url }});

}

</style>

</head>

However, for larger-scale sites where the CSS references a lot of static images, this quickly becomes hard to manage. In that case, you’ll want to use a tool like PostCSS to rewrite static URLs in your CSS to cdnupload URLs via the key mapping. There’s a PostCSS plugin called postcss-url that you can use to rewrite URLs with a custom transform function.

The CSS rewriting should be integrated into your build or deployment process, as the PostCSS rule will need access to the JSON key mapping that the uploader wrote out.

cdnupload is a Python command-line script, but it’s also a Python module you can import and extend if you need to customize it or hook into advanced features. It works on both Python 3.5+ and Python 2.7.

The most likely reason you’ll need to extend cdnupload is to write a custom Destination subclass (if the built-in file or Amazon S3 destinations don’t work for you).

For example, if you’re using a CDN that connects to an origin server called “My Origin”, you might write a custom subclass for uploading to your origin. You’ll need to subclass cdnupload.Destination and implement an initalizer as well as the __str__, walk_keys, upload, and delete methods:

import cdnupload

import myorigin

class Destination(cdnupload.Destination):

def __init__(self, url, foo='FOO', bar=None):

"""Initialize destination instance with given "My Origin" URL

(which should be in form my://server/path).

"""

self.url = url

self.conn = myorigin.Connection(url, foo=foo, bar=bar)

def __str__(self):

"""Return a human-readable string for this destination."""

return self.url

def walk_keys(self):

"""Yield keys (files) that are currently on the destination."""

for file in self.conn.get_files():

yield file.name

def upload(self, key, source, rel_path):

"""Upload a single file from source at rel_path to destination

at given key. Normally this function will use the with statement

"with source.open(rel_path)" to open the source file object.

"""

with source.open(rel_path) as source_file:

self.conn.upload_file_obj(source_file, key)

def delete(self, key):

"""Delete a single file on destination at given key."""

self.conn.delete_file(key)

To use this custom destination, save your custom code to cdnupload_my.py and ensure the file is somewhere on your PYTHONPATH. Then if you run the cdnupload command-line tool with a destination starting with scheme my://, it will automatically import cdnupload_my and look for a class called Destination, passing the my://server/path URL and any additional destination arguments to your initializer.

Note that when the command-line tool passes additional dest_args to a custom destination, it always passes them as strings (or a list of strings if a dest arg is specified more than once). So if you need an integer or other type, you’ll need to convert it in your __init__ method.

The top-level functions upload() and delete() drive cdnupload. You can create your own command-line entry point if you want to hook into cdnupload’s Python API. For example, you could make a myupload.py script as follows:

import cdnupload

import hashlib

source = cdnupload.FileSource('/path/to/my/statics',

hash_class=hashlib.md5)

destination = cdnupload.S3Destination('s3://bucket/path')

cdnupload.upload(source, destination)

Here we’re doing some light customization of FileSource’s hashing behaviour (changing it from SHA-1 to MD5) and then performing an upload.

The upload() function uploads files from a source to a destination, but only if they’re missing at the destination (according to destination.walk_keys).

The delete() function deletes files from the destination if they’re no longer present at the source (according to source.build_key_map).

Both upload and delete take the same set of arguments:

source: the source object; either aFileSourceinstance (or object that implements the same interface), or a string in which case it gets converted to a source viaFileSource(source)destination: the destination object; either an instance of a concreteDestinationsubclass, or a string in which case it gets converted to a destination viaFileDestination(destination)force=False: if True, same as specifying the--forcecommand line optiondry_run=False: if True, same as specifying the--dry-runcommand line optioncontinue_on_errors=False: if True, same as specifying the--continue-on-errorscommand line option

Both functions return a Result namedtuple, which has the following attributes:

source_key_map: the source path to destination key mapping, the same dict returned bysource.build_key_map()destination_keys: a set containing the destination keys, as returned bydestination.walk_keys()num_scanned: total number of files scanned (source files when uploading, or destination keys when deleting)num_processed: number of files processed (actually uploaded or deleted)num_errors: number of errors (useful whencontinue_on_errorsis true)

You can also customize the source of the files. There’s currently only one source class, FileSource, which reads files from the filesystem and produces file hashes. You can pass options to the FileSource initializer to control which files it includes or excludes, as well as how it hashes their contents to produce the content-based hash.

The dot_names, include, exclude, ignore_walk_errors, follow_symlinks, and hash_length arguments correspond directly to the --dot-names, --include, --exclude, --ignore-walk-errors, --follow-symlinks, and --hash-length command line options.

Additionally, you can customize FileSource further with the hash_chunk_size and hash_class arguments. The file is read in hash_chunk_size-byte blocks when being hashed, and hash_class is instantiated to generate the hashes (must have a hashlib-style signature).

Or you can subclass FileSource if you want to customize advanced behaviour. For example, you could override FileSource.hash_file()’s handling of text and binary files to treat all files as binary:

from cdnupload import FileSource

class BinarySource(FileSource):

def hash_file(self, rel_path):

return FileSource.hash_file(self, rel_path, is_text=False)

To use a subclassed FileSource, you’ll need to call the upload() and delete() functions with your instance directly from Python. It’s not currently possibly to use a subclassed source via the cdnupload command line script.

cdnupload functions use standard Python logging to log all operations. The name of the logger is cdnupload, and you can control log output format and verbosity (log level) using the Python logging functions.

For example, to log all errors but turn debug-level logging on only for cdnupload logs, you could do this:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.ERROR)

logging.getLogger('cdnupload').setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

If you find a bug in cdnupload, please open an issue with the following information:

- Full error messages or tracebacks

- The cdnupload version, Python version, and operating system type and version

- Steps or a test case that reproduces the issue (ideally)

If you have a feature request, documentation fix, or other suggestion, open an issue and we’ll discuss!

See also CONTRIBUTING.md in the cdnupload source tree.

cdnupload is licensed under a permissive MIT license: see LICENSE.txt for details.

Note that prior to August 2017 it was licensed under an AGPL plus commercial license combination, but now it's completely free.

cdnupload is written and maintained by Ben Hoyt: a software developer, Python contributor, and general all-round software geek. For more info, see his personal website at benhoyt.com.