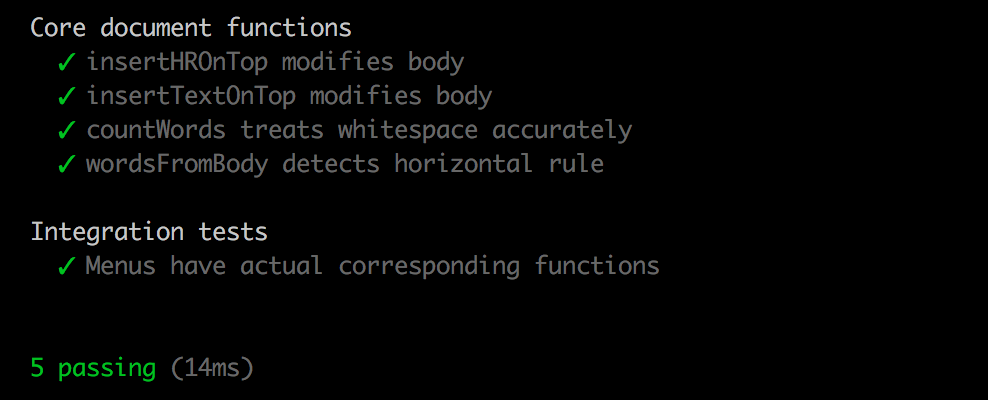

Proof of concept of a local development / push toolchain for Google Apps Scripting. This is an example Google Apps Script application developed on the local machine, complete with js linting/hinting, unit tests ... its features were even tested via a local browser.

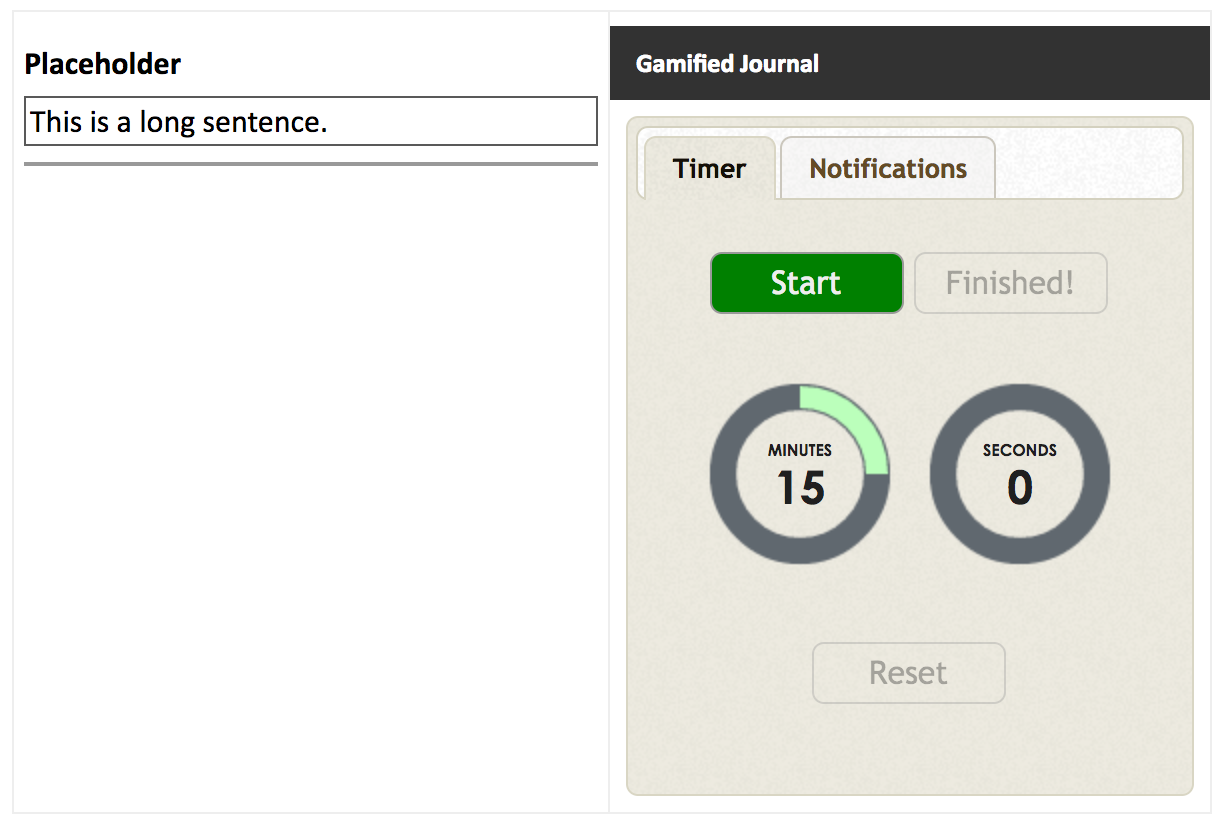

The (simple) app itself does the following for a Google Doc:

- Provides a countdown (from 15 minutes)

- Updates the document in the style of a journal

- Reports the number of words typed and how long they spent typing it

- Make a new google app standalone script on your domain, note the project ID.

- Clone this repo. Note that most of the code lives in

dev/ - Install node.js

npm install- Authenticate with gapps, init with the project ID noted above

./upload- Refresh your GAS script to see the code applied.

- Select "Project" -> "Test as add on"

You now have a gamified journal running on a document.

- Run the app, as above

- Install nodemon to your system path:

npm install nodemon -g - Run the app locally, running

test/server.sh - Load

http://localhost:8888/Sidebarin your browser of choice (must support Proxy) - Any changes in the

dev/folder automatically reflect in the browser (after refresh) - Publish to the cloud with

./upload, which copies files tosrc/and then rungapps uploadfor you (which usessrc/as the source to copy to the cloud) - Changes are now reflected in the cloud (reload and test)

Use live, functional tests in the browser:

$ test/server.sh

You can write your javascript code as if you were writing for the cloud, but locally calls to things like google.script.run are mocked.

It uses gas-local that works by putting the code that works on the cloud as expected, but can be called locally. Templates also have access to that code.

One of the key design decisions that makes this work is the templating package chosen: ejs. That uses a php-style of templating that is very similar to the templating language that Apps Script uses. The minor differences were easy to code up a work-around.

The differences in the local stack compared to the Apps Script stack can be seen most striking in getting a templating language working for both endpoints. This was only possible to do by having two different code paths happen, executing according to whether it was on a production environment (Google's cloud) or in a development environment. On a production environment we include javascript and css files by (according to best practices) using an include() function, which is hand-written App Script code function declaration living in the global scope. The templating language on node.js also has an include function, but if the include function is defined that takes precedence. So instead, we can put include function in the src/ directory, for the production side, and in dev/ the templating feature will remain intact for node.js.

This was only possible unless a strong distiction was made between the two, thus the idea to have a dev/ folder instead of developing within src/.

Entry points to display a template in the browser is simply /Name, and this features is presented in the local server-side code. The virtualization process described below is passed onto the top-level template. It can be passed on to the next layer via virtual.

Minor differences between ejs templating language and Google's templating system are worked around in the code that presents a server in the local environment, by string-replacing the relevant bits to work locally with the ejs system; thus the developer writes with the Google templating language but gets ejs for free locally. In order for the templating language to contain a copy of the virtualized server-side code, we pass it as an option on the local stack. This allows you to put css in a seperate file, per best practices:

<?= include('javascript', virtual()); ?> # note the call to virtual

On local, this will result in ejs system looking for "javascript.ejs" which is created in the server code (and deleted upon exit) but on production Google will present "javascript.html". Thus, the developer works on "javascript.html".

Using gas-local, there is a way to load them up into a context, the next step was passing it onto the templating feature, which already included a way to pass around a global context with the include() call.

So we can just set up a fake object that includes a DocumentApp property, which has a method for getActiveDocument, which return an object that has a getBody method, and so on. We also need to save state as we go, and for this, the javascript closure pattern is quite useful. If needed, we could also use the sinon package.

The client-side browser must have a way of communicating with the execution APIs in order to run server-side code, and google.script.run is the way to interface with it. Locally, we can't virtualize it, because this is client-side code running in the browser, after the template has produced the html/css/javascript. So instead the design decision was to enable the ability for the local environment to include a development.html file, but does nothing when in production. This file implements a google object with all the same properties, and withSuccessHandler and friends are implemented via Promises.

To get this two-fanged approach working right, it was decided to be able to include a file locally, and implement it as a comment. Consider this valid Google template line:

<? /* do nothing, I am just a comment */ ?>

And since we already have include code running on the local machine, I figured design-wise the most elegant way to do this would be to have a conventional statement that would get converted into a normal include statement, but in production wouldn't get converted, and would remain as a comment:

<?= /* include('development.html'); /* ?> <!-- NOTE: The equals is what is expected on the Google side, for unescaped code -->

Before sending this code onto the templating engine locally, we convert that into a normal include call, so it looks like this:

<?- include('development.html'); ?> <!-- NOTE: The hyphen is what is expected on the local side, for unescaped code -->

And it'll be included, via the process explained above. But on production, it'll do nothing since it'll still be just a comment!

Work that is left to do is to figure out how to abstract that away so we can more conveniently reuse that code, instead of having to re-invent the wheel.