fastcall is a foreign function interface library which aim is to provide an easy to use, 100% JavaScript based method for developers to use native shared libraries in Node.js, without needing to touch anything in C++ and without sacrificing too much performance. It's designed with performance and simplicity in mind, an it has comparable function call overhead with hand made C++ native modules. See the benchmarks.

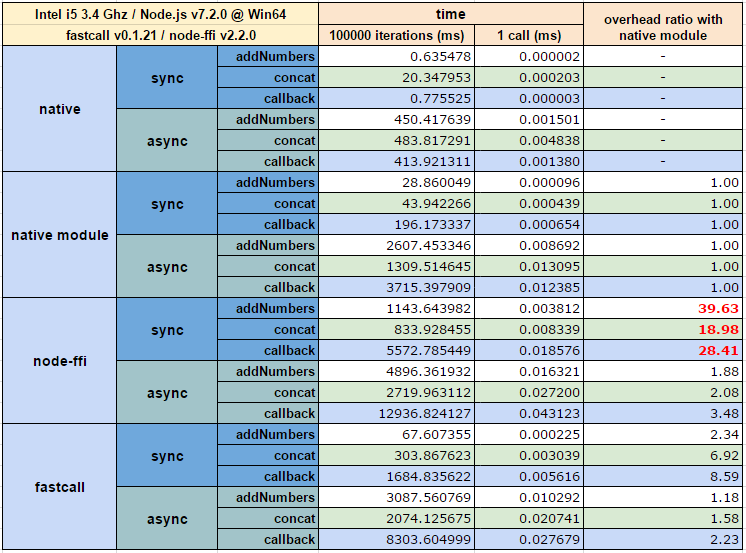

There is a a popular dynamic binding library for Node.js: node-ffi. Then why we need another one could ask? For performance! There is a good 20x-40x function call performance overhead when using node-ffi compared to hand made C++ native module, which is unacceptable in most cases (see the benchmarks).

- uses CMake.js as of its build system (has no Python 2 dependency)

- based on TooTallNate's excellent ref module and its counterparts (ref-struct, ref-array and ref-union), it doesn't try to reinvent the wheel

- has an almost 100% node-ffi compatible interface, could work as a drop-in replacement of node-ffi

- RAII: supports deterministic scopes and automatic, GC based cleanup

- supports thread synchronization of asynchronous functions

- CMake

- A proper C/C++ compiler toolchain of the given platform

- Windows:

- Visual C++ Build Tools or a recent version of Visual C++ will do (the free Community version works well)

- Unix/Posix:

- Clang or GCC

- Ninja or Make (Ninja will be picked if both present)

- Windows:

npm install --save fastcallgit clone --recursive https://github.com/cmake-js/fastcall.git

cd fastcall

npm installFor subsequent builds, type:

cmake-js compileBut don't forget to install CMake.js as a global module first:

npm install -g cmake-jsTo run benchmarks, type:

node benchmarksResults:

There are 3 tests with synchronous and asynchronous versions:

- addNumbers: simple addition, intended to test function call performance

- concat: string concatenation, intended to test function call performance when JavaScript string to C string marshaling required, which is costly.

- callback: simple addition with callbacks, intended to test how fast native code can call JavaScript side functions

All tests implemented in:

- native: C++ code. Assuming function call's cost is almost zero and there is no need for marshaling, its numbers shows the run time of test function bodies

- native module: Nan based native module in C++. This is the reference, there is no way to be anything to be faster than this. fastcall's aim is to get its performance as close as possible to this, so the overhead ratio got counted according to its numbers

- node-ffi: binding with node-ffi in pure JavaScript

- fastcall: binding with fastcall in pure JavaScript

Yeah, there is a room for improvement at fastcall side. Improving marshaling and callback performance is the main target of the future development.

Central part of fastcall is the Library class. With that you can load shared libraries to Node.js' address spaces, and could access its functions and declared types.

class Library {

constructor(libPath, options);

isSymbolExists(name);

release();

declare(); declareSync(); declareAsync();

function(); syncFunction(); asyncFunction();

struct();

union();

array();

callback();

get functions();

get structs();

get unions();

get arrays();

get callbacks();

get interface();

}Constructor:

libPath: path of the shared library to load. There is no magical platform dependent extension guess system, you should provide the correct library paths on each supported platforms (osmodule would help). For example, for OpenCL, you gotta passOpenCL.dllon Windows, andlibOpenCL.soon Linux, and so on.options: optional object with optional properties of:defaultCallMode: either the defaultLibrary.callMode.sync, which means synchronous functions will get created, orLibrary.callMode.asyncwhich means asynchronous functions will get created by defaultsyncMode: either the defaultLibrary.syncMode.lock, which means asynchronous function invocations will get synchronized with a library global mutex, orLibrary.syncMode.queuewhich means asynchronous function invocations will get synchronized with a library global call queue (more on that later)

Methods:

isSymbolExists: returns true if the specified symbol exists in the libraryrelease: release loaded shared library's resources (please note thatLibraryis not aDisposablebecause you'll need to call this method in very rare situations)declare: parses and process a declaration string. Its functions are declared with the default call modedeclareSync: parses and process a declaration string. Its functions are declared as synchronousdeclareAsync: parses and process a declaration string. Its functions are declared as asynchronousfunction: declares a function with the default call modesyncFunction: declares a synchronous functionasyncFunction: declares an asynchronous functionstruct: declares a structureunion: declares an unionarray: declares an arraycallback: declares a callback

Properties:

functions: declared functions (metadata)structs: declared structures (metadata)unions: declared unions (metadata)arrays: declared arrays (metadata)callbacks: declared callbacks (metadata)

Let's take a look at ref before going into the details (credits for TooTallNate). ref is a native type system with pointers and other types those are required to address C based interfaces of native shared libraries. It also has a native interface compatible types for structs, unions and arrays.

In fastcall there are a bundled versions of ref, ref-array, ref-struct and ref-union. Those are 100% compatible with the originals, they are there because I didn't wanted to have a CMake.js based module to depend on anything node-gyp based stuff. Bundled versions are built with CMake.js. The only exception is ref-array, fastcall's version contains some interface breaking changes for the sake of a way much better performance.

const fastcall = require('fastcall');

// 100% ref@latest built with CMake.js:

const ref = fastcall.ref;

// 100% ref-struct@latest

const StructType = fastcall.StructType;

// 100% ref-union@latest

const UnionType = fastcall.UnionType;

// modified ref-struct@latest

const ArrayType = fastcall.ArrayType;ref-array changes:

See the original FAQ there: https://github.com/TooTallNate/ref-array

There are two huge performance bottleneck exists in this module. The first is the price of array indexer syntax:

const IntArray = new ArrayType('int');

const arr = new IntArray(5);

arr[1] = 1;

arr[0] = arr[1] + 1;Those [0] and [1] are implemented by defining Object properties named "0" and "1" respectively. For supporting a length of 100, there will be 100 properties created on the fly. On the other hand those indexing numbers gets converted to string on each access.

Because of that, fastcalls version uses get and set method for indexing:

const IntArray = new ArrayType('int');

const arr = new IntArray(5);

arr.set(1, 1);

arr.set(0, arr.get(1) + 1);Not that nice, but way much faster than the original.

The other is the continous reinterpretation of a dynamically sized array.

const IntArray = new ArrayType('int');

const outArr = ref.refType(IntArray);

const outLen = ref.refType('uint');

myLib.getIntegers(outArr, outLen);

const arr = outArr.unref();

const len = outLen.unref();

// arr is an IntArray with length of 0

// but we know that after the pointer

// there are a len number of element elements,

// so we can do:

for (let i = 0; i < len; i++) {

console.log(arr[i]);

}So far so good, but in each iteration arr will gets reinterpreted to a new Buffer with a size that would provide access to an item of index i. That's slow.

In fastcall's version array's length is writable, so you can do:

arr.length = len;

for (let i = 0; i < len; i++) {

console.log(arr.get(i));

}Which means only one reinterpret, and this is a lot of faster than the original.

Unfortunately those are huge interface changes, that's why it might not make it in a PR.

The interface uses ref and co. for its ABI.

For declaring functions, you can go with a node-ffi like syntax, or with a C like syntax.

Examples:

const fastcall = require('fastcall');

const Library = fastcall.Library;

const ref = fastcall.ref;

const lib = new Library('bimbo.dll')

.function('int mul(int, int)') // arg. names could be omitted

.function('int add(int value1, int)')

.function('int sub(int value1, int value2)')

.function({ div: ['int', ['int', 'int']] })

.function('void foo(void* ptr, int** outIntPtr)')

.function({ poo: ['pointer', [ref.types.int, ref.refType(ref.types.float)]] });Declared functions are accessible on the lib's interface:

const result = lib.interface.mul(42, 42);Sync and async:

About sync and async modes please refer for fastcall.Library's documentation.

If a function is async, it runs in a separate thread, and the result is a Bluebird Promise.

const lib = new Library(...)

.asyncFunction('int mul(int, int)');

lib.interface.mul(42, 42)

.then(result => console.log(result));You can always switch between a function's sync and async modes:

const lib = new Library(...)

.function('int mul(int, int)');

const mulAsync = library.interface.mul.async;

const mulSync = mulAsync.sync;

assert.strictEqual(mulSync, library.interface.mul);

assert.strictEqual(mulAsync, mulSync.async.async.sync.async);You get the idea.

Concurrency and thread safety:

By default, a library's asynchronous functions are running in parallel distributed in libuv's thread pool. So they are not thread safe.

For thread safety there are two options could be passed to fastcall.Library's constructor: syncMode.lock and syncMode.queue.

With lock, a simple mutex will be used for synchronization. With queue, all of library's asynchronous calls are enqueued, and only one could execute at once. The former is a bit slower, but that allows synchronization between synchronous calls of the given library. However the latter will throw an exception if a synchronous function gets called while there is an asynchronous invocation is in progress.

Metadata:

In case of:

const lib = new Library(...)

.function('int mul(int value1, int value2)');lib.functions.mul gives the same metadata object's instance as lib.interface.mul.function.

- properties:

name: function's nameresultType: ref type of the function's resultargs: is an array of argument objects, with properties ofname: name of the argument (arg[n] when the name was omitted)type: ref type of the given argument

- methods

toString: gives function's C like syntax

Easy as goblin pie. (Note: struct interface is ref-struct, and union is ref-array based.)

You can go with the traditional (node-ffi) way:

const fastcall = require('fastcall');

const StructType = fastcall.StructType;

// Let's say you have a library with a function of:

// float dist(Point* p1, Pint* p2);

const Point = new StructType({

x: 'int',

y: 'int'

});

const lib = new Library(...)

.function({ dist: ['float', [ref.refType(Point), ref.refType(Point)]] });

const point1 = new Point({ x: 42, y: 42 });

const point2 = new Point({ x: 43, y: 43 });

const dist = lib.interface.dist(point1.ref(), point2.ref());But there is a better option. You can declare struct on library interfaces, and this way, fastcall will understand JavaScript structures on function interfaces.

Declaring structures:

// object syntax

lib.struct({

Point: {

x: 'int',

y: 'int'

}

});

// C like syntax

lib.struct('struct Point { int x; int y; }');After that the structure is accessible on library's structs property:

const pointMetadata = lib.structs.Point;metadata properties:

name: struct's nametype: struct's ref type (exactly likePointin the first example)

The real benefit is that, by this way - because the library knows about your structure - you can do the following:

lib.function({ dist: ['float', ['Point*', 'Point*']] });

// --- OR ---

lib.function('float dist(Point* point1, Point* point2)');

// --- THEN ---

const result =

lib.interface.mul({ x: 42, y: 42 }, { x: 43, y: 43 });Way much nicer and simpler syntax like the original, ain't it?

About unions:

Declaring unions is exactly the same, except 'union' used instead of 'struct' on appropriate places. (Note: struct interface is ref-union based.)

lib

.union('union U { int x, float y }')

.function('float pickFloatPart(U* u)');

const f = lib.interface.pickFloatPart({ y: 42.2 });

// f is 42.2Declaring arrays is not much different than declaring structures and unions. There is one difference: arrays with fixed length are supported.

// C code:

// a struct using fixed length array

struct S5 {

int fiveInts[5];

};

// a astruct using an arbitrary length array

struct SA {

int ints[]; // or: int* ints;

};

// example functions:

// prints five values

void printS5(S5* s);

// print length number of values

// length is a parameter, because SA knows nothing about

// the length of SA.ints

void printSA(SA* s, int length);Access those in fastcall:

lib

.array('int[] IntArray') // arbitrary length

.struct('struct S5 { IntArray[5] ints; }')

.struct('struct SA { IntArray[] ints; }') // or: IntArray ints

.function('void printS5(S5* s)')

.function('void printSA(SA* s, int len)');

lib.interface.printS5({ ints: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] });

lib.interface.printSA({ ints: [1, 2, 3] }, 3);Of course object syntax is available too:

lib

.array({ IntArray: 'int' }) // arbitrary length

.struct({ S5: { ints: 'IntArray[5]' } })

.struct({ SA: { ints: 'IntArray' } })

.function({ printS5: ['void', ['IntArray[5]']] })

.function({ printSA: ['void', ['IntArray', 'int']] });After that the array is accessible on library's arrays property:

const intArrayMetadata = lib.arrays.IntArray;metadata properties:

name: array's namelength: number if fixed length, null if arbitrarytype: array's ref type

Of course you can declare fixed length arrays directly:

lib.array('int[4] IntArray4');And any fixed or arbitrary length array type could get resized on usage:

lib

.struct('struct S5 { IntArray4[5] ints; }')

.struct('struct SA { IntArray4[] ints; }')fastcall.Library's declare, declareSync and declareAsync functions could declare every type of stuff at once.

So the array example could be written like:

lib.declare('int[] IntArray;' +

'struct S5 { IntArray[5] ints; };' +

'struct SA { IntArray[] ints; };' +

'void printS5(S5* s);' +

'void printSA(SA* s, int len);');You can create native pointers for arbitrary JavaScript functions, and by this way you can use JavaScript functions for native callbacks.

// C code

typedef int (*TMakeIntFunc)(float, double);

int bambino(float fv, double dv, TMakeIntFunc func)

{

return (int)func(fv, dv) * 2;

}To drive this, you need a callback and a function on your fastcall based library defined. It could get declared by object syntax:

lib

.callback({ TMakeIntFunc: ['int', ['float', 'double']] })

.function({ bambino: ['int', ['float', 'double', 'TMakeIntFunc']] });

const result = lib.interface.bambino(19.9, 1.1, (a, b) => a + b);

// result is 42Or with a familiar, C like syntax:

lib

.declare('int (*TMakeIntFunc)(float, double);' +

'int bambino(float fv, double dv, TMakeIntFunc func)');

const result = lib.interface.bambino(19.9, 1.1, (a, b) => a + b);

// result is 42Callback's metadata are accessible on library's callbacks property:

const TMakeIntFuncMetadata = lib.callbacks.TMakeIntFunc;- metadata properties:

name: callbacks's nameresultType: ref type of the callbacks's resultargs: is an array of argument objects, with properties ofname: name of the argument (arg[n] when the name was omitted)type: ref type of the given argument

- methods

toString: gives callbacks C like syntax

If you wanna use you callbacks, structs, unions or arrays more than once (in a loop, for example), without being changed, you can create a (ref) pointer from them, and with those, function call performance will be significantly faster. Callback, struct, union and array factories are just functions on library's property: interface.

For example:

// ref-struct way

const StructType = require('fastcall').StructType; // or require('ref-struct')

const MyStruct = new StructType({ a: 'int', b: 'double' });

const struct = new MyStruct({ a: 1, b: 1.1 });

const ptr = struct.ref(); // ptr instanceof Buffer

lib.interface.printStruct(ptr);

// fastcall way

lib.declare('struct StructType { int a; double b; }');

const ptr = lib.interface.StructType({ a: 1, b: 1.1 });

// ptr instanceof Buffer

// You can create the modifyable struct instance of course

// by using the metadata property: type

const structMetadata = lib.structs.StructType;

const struct = structMetadata.type({ a: 1, b: 1.1 });

// ...

struct.a = 2;

struct.b = 0.1;

// ...

const ptr = struct.ref();

// or

const ptr = lib.interface.StructType(struct);Or with callbacks:

lib.declare('void (*CB)(int)');

const callbackPtr = lib.interface.CB(x => x * x);

// callbackPtr instanceof Buffer

lib.interface.someNativeFunctionWithCallback(42, callbackPtr);

// that's a slightly faster than:

lib.interface.someNativeFunctionWithCallback(42, x => x * x);string pointers:

For converting JavaScript string to (ref) pointers back and forth there are ref.allocCString() and ref.readCString() methods available.

However for converting JavaScript strings to native-side read-only strings there is a much faster alternative available in fastcall:

fastcall.makeStringBuffer([string] str)

Example:

const fastcall = require('fastcall');

// ...

lib.declare('void print(char* str)');

const ptr = fastcall.makeStringBuffer(

'Sárgarigó, madárfészek, ' +

'az a legszebb, aki részeg');

lib.interface.print(ptr);

// that's faster than writing:

lib.interface.print(

'Sárgarigó, madárfészek, ' +

'az a legszebb, aki részeg');Native resources must get freed somehow. We can rely on Node.js' garbage collector for this task, but that would only work if our native code's held resources are memory blocks. For other resources it is more appropriate to free them manually, for example in try ... finally blocks. However, there are more complex cases.

Let's say we have a math library that works on the GPU with vectors and matrices. A complex formula will create a bunch of temporary vectors and matrices, that will hold a lot memory on the GPU. In this case, we cannot rely on garbage collector of course, because that knows nothing about VRAM. Decorating our formula with try ... finally blocks would be a horrible idea in this complex case, just think about it:

const vec1 = lib.vec([1, 2, 3]);

const vec2 = lib.vec([4, 5, 6]);

const result = lib.pow(lib.mul(vec1, vec2), lib.abs(lib.add(vec1, vec2)));

// would be something like:

const vec1 = lib.vec([1, 2, 3]);

const vec2 = lib.vec([4, 5, 6]);

let tmpAdd = null, tmpAbs = null, tmpMul = null;

let result;

try {

tmpAdd = lib.add(vec1, vec2);

tmpAbs = lib.abs(tmpAdd);

tmpMul = lib.mul(vec1, vec2);

result = lib.pow(tmpMul, tmpAbs);

}

finally {

tmpAdd && tmpAdd.free();

tmpMul && tmpMul.free();

tmpAbs && tmpAbs.free();

}So we need an automatic, deterministic scoping mechanism for JavaScript for supporting this case. Like C++ RAII or Python's __del__ method.

The good news is all three mentioned techniques are supported in fastcall.

For accessing fastcall's RAII features you need a class that inherits from Disposable. It's a very simple class:

class Disposable {

constructor(disposeFunction, aproxAllocatedMemory);

dispose();

resetDisposable(disposeFunction, aproxAllocatedMemory);

}disposeFunction: could be null or a function. If null, thenDisposabledoesn't dispose anything. If a function, then it should release your object's native resources. It could be asynchronous, and should return a Promise on that case (any thenable object will do). Please note that this function has no parameters, and only allowed to capture native handles from the source object, not a reference of the source itself because that would prevent garbage collection! More on this later, please keep reading!aproxAllocatedMemory: in bytes. You could inform Node.js' GC about your object's native memory usage (calls Nan::AdjustExternalMemory()). Will get considered only if it's a positive number.dispose(): will invokedisposeFunctionmanually (for the mentioned try ... catch use cases). Subsequent calls does nothing. You can override this method for implementing custom disposing logic, just don't forget to call its prototype'sdispose()if you passed adisposeFunctiontosuper. IfdisposeFunctionis asynchronous thendipsose()should be asynchronous too by returning a Promise (or any thenable object).resetDisposable(...): reinitializes the dispose function and the allocated memory of the givenDisposable. You should call this, when the underlying handle changed. WARNING: the originaldisposeFunctionis not called implicitly by this method. You can rely on garbage collector to clean it up, or you can calldispose()explicitly prior calling of this method.

Example:

const lib = require('lib');

const fastcall = require('fastcall');

const ref = fastcall.ref;

const Disposable = fastcall.Disposable;

class Stuff {

constructor() {

const out = ref.alloc('void*');

lib.createStuff(out);

const handle = out.defer();

super(

() => {

// you should NEVER mention "this" there

// that would prevent garbage collection

lib.releaseStuff(handle);

},

42 /*Bytes*/);

this.handle = handle;

}

}

// later

let stuff = null;

try {

stuff = new Stuff();

// do stuff :)

}

finally {

stuff && stuff.dispose();

}

// replace the underlying handle:

const stuff = new Stuff();

// get some native handle from anywhere

const out = ref.alloc('void*');

lib.createStuff(out);

const someOtherHandle = out.defer();

// now, stuff should wrap that

// you should implement this in a private method:

stuff.dispose(); // old handle gets released

stuff.resetDisposable(() => lib.releaseStuff(someOtherHandle), 42);

stuff.handle = someOtherHandle;For prototype based inheritance please use Disposable.Legacy as the base class:

function Stuff() {

Disposable.Legacy.call(this, ...);

}

util.inherits(Stuff, Disposable.Legacy);When there is no alive references exist for your objects, they gets disposed automatically once Node.js' GC cycle kicks in (lib.releaseStuff(handle) would get called from the above example). There is nothing else to do there. :) (Reporting approximate memory usage would help in this case, though.)

For deterministic destruction without that try ... catch mess, fastcall offers scopes. Let's take a look at an example:

const scope = require('fastcall').scope;

// Let's say, we have Stuff class

// from the previous example.

scope(() => {

const stuff1 = new Stuff();

// do stuff :)

return scope(() => {

const stuff2 = new Stuff();

const stuff3 = new Stuff();

const stuff4 = fuseStuffs(/*tmp*/fuseStuff(stuff1, stuff2), stuff3);

return stuff4;

});

});Kinda C++ braces.

Rules:

- scope only affects objects whose classes inherits from

Disposable, we refer them as disposables from now on - scope will affect implicitly created disposables also (like that hidden temporary result of the inner

fuseStuffcall of the above example) - all disposables gets disposed on the end of the scope, except returned ones

- returned disposables are propagated to parent scope, if there is one - if there isn't a parent, they escape (see below)

Escaping and compound disposables:

A disposable could escape from a nest of scopes at anytime. This will be handy for creating classes those are a compound of other disposables. Escaped disposable would become a free object that won't get affected further by the above rules. (They would get disposed manually or by the garbage collector eventually.)

class MyClass extends Disposable {

constructor() {

// MyClass is disposable but has no

// direct native references,

// so its disposeFunction is null

super(null);

this.stuff1 = null;

this.stuff2 = null;

scope(() => {

const stuff1 = new Stuff();

// do stuff :)

this.stuff1 = scope.escape(stuff1);

const tmp = new Stuff();

this.stuff2 = scope.escape(fuseStuffs(tmp, stuff1));

});

// at this point this.stuff1 and

// this.stuff2 will be alive

// despite their creator scope got ended

}

dispose() {

// we should override dispose() to

// free our custom objects

this.stuff1.dispose();

this.stuff2.dispose();

}

}

// later

scope(() => {

const poo = new MyClass();

// so this will open a child scope in

// MyClass' constructor that frees its

// temporaries automatically.

// MyClass.stuff1 and MyClass.stuff2 escaped,

// so they has nothing to do with the current scope.

});

// However poo got created in the above scope,

// so it gets disposed at the end,

// and MyClass.stuff1 and MyClass.stuff2 gets disposed at that point

// because of the overridden dispose().Result:

scope's result is the result of its function.

const result = scope(() => {

return new Stuff();

});

// result is the new StuffRules of propagation is described above. Propagation also happens when the function returns with:

- an array of disposables

- a plain objects holding disposables in its values

- Map of disposables

- Set of disposables

This lookup is recursive, and apply for scope.escape()'s argument, so you can escape an array of Map of disposables for example with a single scope.escape() call.

Async:

If a scope's function returns a promise (any then-able object will do) then it turns to an asynchronous scope, it also returns a promise. Same rules apply like with synchronous scopes.

const result = scope(() =>

lib.loadAsync()

.then(loaded => {

// do something with loaded ...

return new Stuff();

}));

result.then(result => {

// result is the new Stuff

});Coroutines:

Coroutines supported by calling scope.async. So the above example turns to:

const result = yield scope.async(function* () {

const loaded = yield lib.loadAsync();

return new Stuff();

})Way much nicer, eh? It does exactly the same thing.

If you happen to have a node-ffi based module, you can switch to fastcall with a minimal effort, because there is a node-ffi compatible interface available:

const fastcall = require('fastcall');

// in

const ffi = fastcall.ffi;

// you'll have

ffi.Library

ffi.Function

ffi.Callback

ffi.StructType // == fastcall.StructType (ref-struct)

ffi.UnionType // == fastcall.UnionType (ref-union)

ffi.ArrayType // == fastcall.ArrayType (ref-array)Works exactly like node-ffi and ref modules. However there are some minor exceptions:

- only

asyncoption supported in library options asyncPromiseproperty is available in functions along withasync, you don't have to relyPromise.promisify()like features- fastcall's version of Library doesn't add default extensions and prefixes to shared library names, so

"OpenCL"won't turn magically to"OpenCL.dll"on windows or"libOpenCL.so"on Linux - fastcall's version of ref-array is modified slightly to have better performance than the original

- NOOOCL: I have recently ported NOOOCL from node-ffi to fastcall. It took only a hour or so thanks to fastcall's node-ffi compatible interface. Take a look at its source code to have a better idea how ref and fastcall works together in a legacy code.

- ArrayFire.js: as soon as I finish writing this documentation, I'm gonna start to work on a brand new, fastcall based version of ArrayFire.js. That will get implemented with fastcall from strach, so eventually you can take a look its source code for hints and ideas of using this library.

- Daniel Adler and Tassilo Philipp - for dyncall

- TooTallNate - ref, ref-array, ref-struct, ref-union and of course node-ffi for inspiration and ideas

Copyright 2016 Gábor Mező (gabor.mezo@outlook.com)

Licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0 (the "License");

you may not use this file except in compliance with the License.

You may obtain a copy of the License at

http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0

Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software

distributed under the License is distributed on an "AS IS" BASIS,

WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied.

See the License for the specific language governing permissions and

limitations under the License.