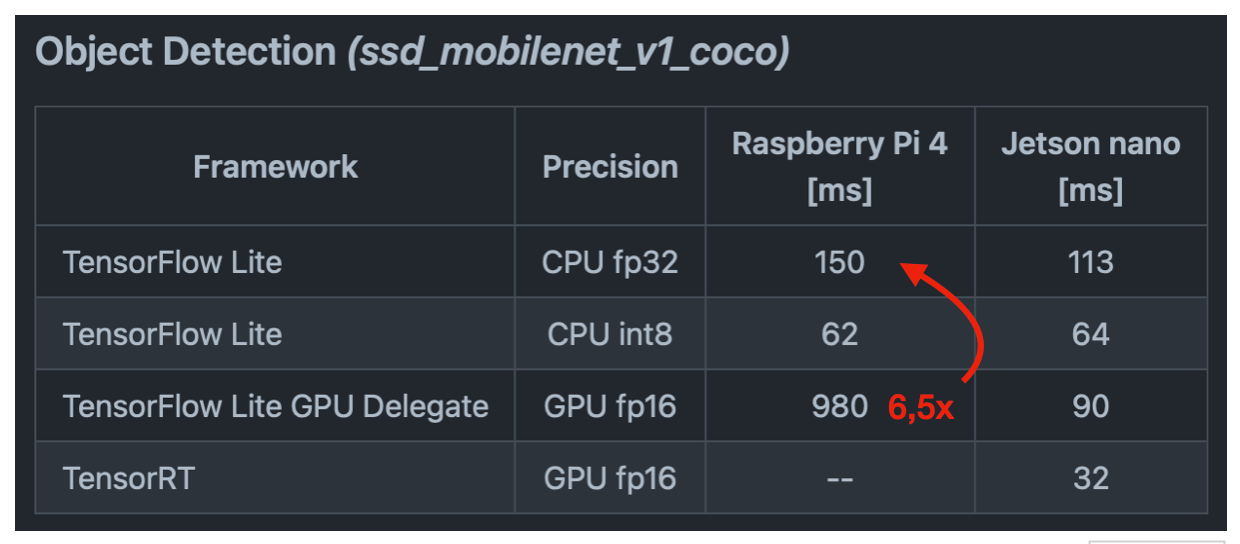

This repository contains code and benchmark results for compute workloads on constrained (non-desktop) GPUs. We started this project after seeing abysymal performance of TensorFlow Lite on embedded systems and after doing some research we noticed we are not alone with this problem:

This seems to be a recurring theme: GPU performance seems to be good on NVidia SoCs and on everything else the ARM CPU is up to 10x faster than the GPU at deep learning inference.

We decided to dive deeper and understand where are the performance limits of mobile GPUs and see how we can push them using Open Source drivers and software. All this to deliver faster and more energy efficient deep learning on embedded systems. (we are also working on Open Sourcing NPUs, see Machine Learning with Etnaviv and OpenCL)

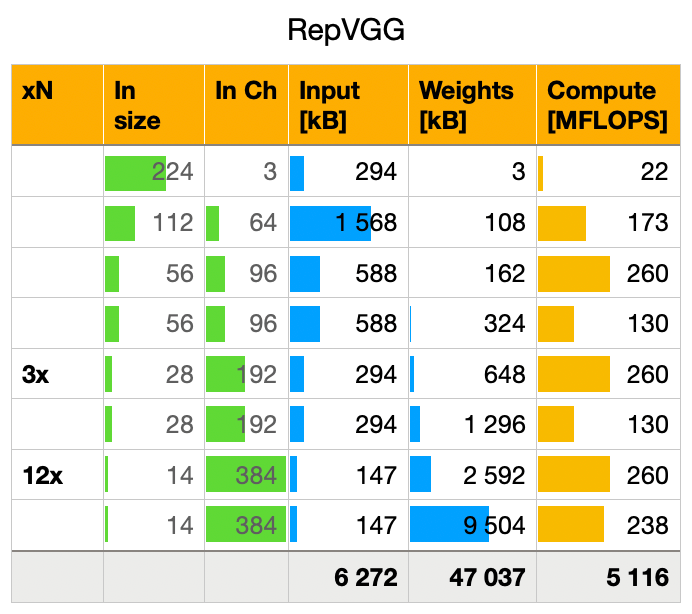

Before we dive into the microbenchmarks we should look into how neural network workloads differ from other compute. Here is a breakdown of a highly effective convolutional neural network (RepVGG A2 which was the precursor to MobileOne the SotA mobile-friendly backbone):

It is composed of 21 convolutional layers (with a nonlinear activation function applied to each output). The layers which do not change the shape of their input were compressed into a single line but in reality they have to be executed multiple times with different parameters.

If you are coming from a DSP background one thing to watch out for is

that the inputs (to all but the first layer) are not monochrome or RGB

but multi-channel images (In size ^ 2 * In Ch). This means that the

convolutional kernels which calculate each output channel using every

input channel end up being pretty big (i.e. 2.5MB for each of the most

compute-intensive 12 layers).

To process the whole network the weights and intermediate outputs have to be transfered between the registers and main memory at least once (most likely hundrends of times unless the on-chip memory is very large). The total size of all the intermediate values is around 6MB and the parameters (kernels) – 47MB.

To process a single 224x224 RGB image with this network we would need 5GFLOPs.

We started on the ARM Mali-G52 which is a widely implemented low-end GPU. The lessons learned should transfer easily to other mobile GPUs since they are (un)suprisingly very similar to each other. Our current findings about the G52 inside the Amlogic A311D:

Compute:

- 76,8 gigainstructions/s (which gives a maximum 38,4 GFLOPS if care only about multiplications)

Memory/cache:

- 128kB of L2 cache

- 16kB L1 cache for the texture unit and another for the load/store unit (64kB of L1 cache for the whole GPU)

- the L1 caches should have up to 95GB/s of peak memory bandwidth (we currently achieved 19,5GB/s)

Register file (the fastest memory):

- there are 768 threads multiplexed onto each core (when they use < 64 registers, half of this otherwise)

- this means the register file has to be 768 ✕ 64 ✕ 32bit = 192kB per core and 384kB for the whole GPU (more then the size of the caches!)

We are still working to verify some of these numbers (especially the cache memory bandwidths) but this already brings an interesting perspective to what we should keep in which memory region if we want to run neural networks efficiently on such a GPU.

Over the coming weeks we will release our micro-benchmarks, hunt down the missing L1 memory bandwidth (or figure out why our estimate is unrealistic) and work on an implementation strategy for some fundamental neural network operators (like the fused convolution+activation and attention).