-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 299

Threat model

End-To-End handles key management and provides end-to-end encryption, decryption, signing and verification capabilities to Web users. As end-to-end encryption is implemented differently in various other solutions, it is necessary to precisely describe the threat model in which End-To-End operates. This document lists End-To-End user assets at issue, and identifies threat sources that might compromise the user’s privacy.

End-To-End deals with the following sensitive assets:

-

Keyrings

- Secret keyring - OpenPGP secret key(s), certifying user identities. Secret keys are used to decrypt incoming messages, and sign outgoing messages. Secret keys also include one or more user identities (often e-mail addresses), each signed by the key. Owning a secret key also implies a claim by its owner to the associated identities (but the validity of such a claim is decided by other users).

- Public keyring - List of OpenPGP Transferable Public Keys imported by the user into End-To-End. Keys in the public keyring are used to encrypt outgoing messages, and verify incoming message signatures. End-to-end currently also assumes that the presence of a key in the user's public keyring implies the user trusts it, along with its associated identities. The public keyring contains the identities of the people with whom the user has exchanged messages, as well as from any imported OpenPGP keys. The public keyring is analogous to the list of contacts of a user.

-

Messages

- Plaintext messages and drafts - Plaintext content of messages encrypted to the user's public key(s) and the plaintext content of draft messages composed by the user.

-

Messages metadata - Subject and recipients of the encrypted messages, including OpenPGP Key IDs of the message recipients, as well as encrypted message attachment filenames. Just like in other OpenPGP-in-webmail implementations, the metadata is disclosed to the web application for convenience (Subject) and the purpose of routing the encrypted message to its intended recipients. OpenPGP clients traditionally encrypt each message attachment separately, exposing to the e-mail providers the number of attachments, their filenames, and ciphertext length. We follow that approach.

In the current version we do not remove the key IDs (

gpg --throw-keyids) from the encrypted messages.

The following adversaries may interfere with End-To-End in order to get access to the protected assets:

-

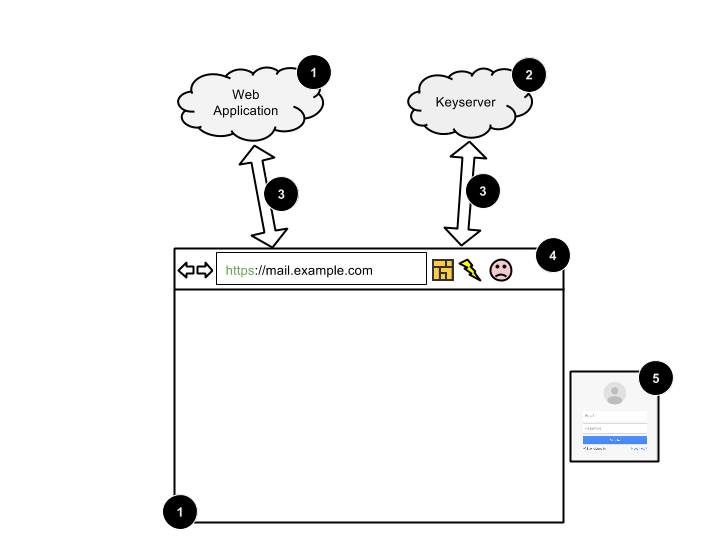

Web application. Web application used to send and receive e-mail messages or other messages protected with OpenPGP. Client-side code of the web application may be vulnerable or altered purposefully in order to attack End-To-End users. The user may be using multiple web applications written by different providers (e.g., Gmail, Yahoo! Mail, Hotmail). It is assumed the web application needs the access to messages metadata in order to deliver the messages (e.g., recipient e-mails need to be exposed for the message to be sent over SMTP).

-

Keyserver. Malicious or compromised OpenPGP keyserver. For an in-depth threat model of End-To-End keyserver integration, check this document.

-

Man-in-the middle (MITM). Attacker that has the ability to inspect and alter the SMTP/HTTP/HKP protocol traffic, circumventing or disabling the transport layer encryption. MITM attackers can modify the web application code to perform large-scale or targeted attacks.

-

Other Chrome Apps and Extensions. All Chrome Extensions installed in the same browser profile as End-To-End. Chrome Apps and Extensions typically request a subset of available platform permissions, but in this threat model we assume extensions have all available permissions, including the permissions to alter any web application and tamper with HTTP traffic. Such Chrome Extensions implicitly have the capabilities to act as a man-in-the-middle and web application threat source.

Since creating the first version of the extension, we have identified a few ways a malicious extension or Chrome App can exfiltrate assets owned by another Chrome Extension. Given that our extension is likely to be used in browsers containing many other extensions and apps we do not control, we believe it is important to identify the threats originating from other extensions and apps.

-

Compromised Google account. Adversary who has access to End-To-End user's Google account either via successful phishing for account credentials, or by breaking into the account (e.g., exploiting account recovery flows or weak passwords). Additionally, the attacker might compromise the user account by exploiting a vulnerability in one of the devices associated with that account but without the key material (e.g., malware installed on user's Android device). A compromised Google account may give the adversary possibilities to install arbitrary Chrome Apps and Extensions into the browser profile with End-To-End through Chrome sync.

We don't provide any countermeasures for threats originating from the following sources, and high-risk users may wish to use additional countermeasures against adversaries in these areas.

-

Browser. In our threat model, the Chrome browser is equivalent to a root user, so it has the capability to circumvent all security mechanisms employed in End-To-End. Users concerned with adversaries able to backdoor the Chrome browser may use End-To-End with open-source Chromium.

Chrome/Blink 0-day vulnerabilities may result in various levels of browser compromise. Adversaries exploiting vulnerabilities in the Chrome browser are explicitly outside our threat model.

-

Native applications. Various native applications installed alongside the browser can access End-To-End assets directly (e.g., via the file system or memory inspection). Asset compromise might also happen by an accidental flaw. For example, an improperly configured backup solution may leak the secret keys stored in a user's Chrome profile to a network adversary or cloud storage provider.

-

Malware. Malicious code running with the full local user privileges on the operating system (e.g., keyloggers). We do not implement any mitigations or speedbumps against malware and assume that no application can reliably protect its assets if the host it's running on is compromised. This is in line with the model adopted by GnuPG, for example. For high-risk users we recommend using an operating system that provides strong protections against malware by design (such as Chrome OS).

-

Operating system. The operating system kernel, together with all device drivers. While some types of malware could be isolated via operating system security mechanisms (e.g. different OS user accounts), if the operating system itself is compromised, all bets are off for End-To-End. As such, keeping your operating system up-to-date and configured correctly is critical.

-

Hardware. Vulnerabilities or backdoors in device hardware, including hard drives, SSD, memory chips, CPU or peripherals. For example, hardware keyloggers, TEMPEST, or even potentially a phone could be used to steal information from a user. Finally, Chrome considers hardware/physical attacks outside of their threat model.

-

Human error. Users may involuntarily expose the protected assets to the adversary, e.g., through social engineering, by giving access to keyring files, or interacting with untrusted UI elements. End-to-End mitigates this (e.g., by providing UI interactions with verifiable indicators) but cannot prevent such errors.

The following threats against the protected assets have been identified:

Chrome Apps and Extensions are capable of taking complete control over the user's browser look and feel. This means that the threats identified below can't be feasibly defended against other apps and extensions (for instance, a Chrome App can always create a window on top of other Chrome Apps).

UI threats in this section assume defending against web applications and man-in-the-middle attackers only, for which both Chrome and End-To-End intend to provide risk mitigation.

If attackers have a possibility to encrypt a message to an additional public key, it would allow them to read the contents of the message. This could be done in multiple ways, e.g., by overlaying the compose message UI element with CSS to cover an additional key, or by exploiting differences in e-mail address formatting.

One way to mitigate this threat is by displaying the compose message dialog only in a trusted, top-most UI element (for example, the Chrome Extension page action). In this trusted UI, we display e-mail addresses certified to use the OpenPGP public key the message would be encrypted to. End-To-End never embeds the compose dialog within the host page, which would permit an untrusted web application to overlay its contents.

Since encryption only uses a recipient's public key, it's trivial for the adversaries to spoof encrypted message contents sent to an End-To-End user. For example, a webmail application may pretend that an arbitrary message has been sent from a given e-mail address as a reply to an End-To-End user message. End-to-end mitigates this by showing a notification when verified OpenPGP signatures are found in the message, or an error when a verifiable signature fails to validate.

A web application or MITM attacker can spoof elements of the End-To-End UI, if such elements are displayed directly within the browser tab displaying the web application. For example, a compose message iframe embedded within the host page could be spoofed or overlaid, disclosing the message draft typed into the compose element to the adversary. Similarly, UI elements displayed in new windows may be covered by pop-ups opened by web applications.

One way End-To-End currently mitigates this is by using a popup from the extension browser action button. UI elements in such popup cannot be overlaid, and the popup itself cannot be fully spoofed by web applications. The extension icon and relevant popup serve as trust indicators for the End-To-End trusted UI. Given those indicators, the user may verify they are interacting with an End-To-End UI element, and not a malicious web application.

We do not protect against web applications using HTML5 fullscreen API, as any trust indicator can be spoofed by them. However, browsers supporting the fullscreen API display a warning when a web application activates fullscreen mode, providing users with an option to cancel their interaction.

Unlike web applications, malicious Chrome Extensions (e.g., extensions installed through a compromised user account) can re-use the End-To-End icon to trick users into thinking they are interacting with a legitimate End-To-End extension. Such an extension can then exfiltrate any draft message contents and message recipient identities. Similarly, a malicious Chrome App can spoof the whole screen imitating even the browser chrome.

However, even a spoofing extension or app does not have access to secret key material, so secret keys cannot be leaked, past messages cannot be decrypted, and the messages created in the spoofing extension cannot be signed.

Users might involuntarily disclose plaintext of the message, e.g., by composing them inside web applications (e.g., composing a draft of the message in a webmail application). This, however, is a human error outside our threat model. However, we try to mitigate the risk of disclosing the message contents in other ways by:

- not exposing an API for message decryption

- providing our own compose and read message interface in a trusted UI (Chrome Extension page action)

- using various timing sidechannel preventions (constant-time BigInteger operations, RSA blinding)

Nevertheless, we'd like to also mention the following side channels that might still leak the plaintext of the messages. For those we offer no mitigation.

-

Recipient actions. End-To-End cannot guarantee the confidentiality of the message as it is processed by its intended recipients. The recipient might disclose the message in various ways. For example, commonly e-mail message replies contain quoted contents of the original message. The reply message can be encrypted to a different set of keys (including the key an adversary has control of), or might not even be encrypted at all.

-

Clipboard. Plaintext of the message can be leaked by the user involuntarily via the OS clipboard. The web application cannot directly read the clipboard, but an adversary may use social engineering to entice the user to paste into a textarea ("Press CTRL, and press V"). However, all Chrome Extensions with the

clipboardReadpermission may read any plaintext messages copy/pasted to or from the compose window. -

Files. When using End-To-End to encrypt files, the plaintext version of the file is always stored on the filesystem. Adversaries having direct access to files are outside our threat model.

In previous versions of the extension, users could use the feature of End-To-End ("Looking Glass") that displays the plaintext of a message the user has clicked on in a web application document. It protected the plaintext of the decrypted message in the following ways:

-

Same Origin Policy - Message was displayed in an IFRAME of End-To-End

chrome-extension://origin, so web applications could not inspect the context of the iframe. - Constant-size. We did not leak the dimensions of the decrypted text by setting the size of the iframe before decryption.

- Throttling. We throttled the requests for displaying the IFRAME, to prevent side-channel attacks requiring multiple accesses to the oracle.

- Timing sidechannel prevention. Random delay for displaying an iframe was added on top of our standard timing sidechannel countermeasures.

However, we discovered that Chrome Extensions can also use chrome.tabs.captureVisibleTab to take a screenshot of current tab in any browser window. Screenshot would also include rendered contents of cross-origin iframes, potentially leaking the message plaintext displayed in Looking Glass iframes added to a web application document. To mitigate the risk of message plaintext leaks through Looking Glass, that feature was disabled in the code.

Similar to message plaintext leaks, the adversary could get access to a decryption oracle, allowing them to decrypt multiple messages without user interaction.

Countermeasures against this threat are already mentioned in Message plaintext leaks section, but it's worth noting that a malicious Chrome Extension could abuse the "Looking Glass" feature to take screenshots of arbitrary messages in the background window without user interaction. The speed of the attack would be limited only by API throttling and the time of the actual decryption. The Looking Glass feature is now disabled.

OpenPGP message format allows for limited tampering with the messages if Symmetrically Encrypted Data Packets (Tag 9) lacking integrity protection are used.

In accordance to RFC 4880, End-To-End uses Symmetrically Encrypted Integrity Protected Data Packets (Tag 18) when composing messages and verifies the MDC code when processing messages with Tag 18 packets. Messages using the tag 9 packet are still accepted due to compatibility reasons.

Additionally, messages created with End-To-End are signed with the user's private key by default (user has an option to choose the signing key or disable the signature for an individual message).

A web application (e.g., a webmail provider) can reshuffle encrypted messages or not deliver them to an End-To-End user or any of the recipients. Though it is possible to introduce additional metadata to maintain conversation integrity, it falls outside the scope of OpenPGP, so we do not mitigate this threat.

Identities present in a public keyring carry the information of who an End-To-End user has communicated with in the past. While this data may be considered private, it is worth noting that some information leaks are inevitable, as this information can be obtained from other sources.

For example, End-To-End does not remove the Key IDs from outgoing OpenPGP messages, so they are accessible to relevant web application and man-in-the-middle adversaries. In general, we believe that short of generating a throwaway OpenPGP key for every message exchange, users cannot reliably protect themselves from adversaries observing message metadata to discover communication participants.

Nevertheless, we recognize the need to limit access to all keyring identities to all components interacting with End-To-End. For example, a user (e.g., a journalist) might manually import a recipient (e.g., a whistleblower) public key into his or her keyring and intend to use End-To-End only for encryption and decryption of messages exchanged with this recipient over a non-web-based external channel. In this case the presence of the key should not be disclosed to the keyserver or various web applications.

We mitigate this threat by not exposing the API to reveal identities in user's public keyring to web applications. Additionally, only a user's own public key is uploaded to the keyserver, and only upon a key generation.

Web applications can initiate a message compose flow using an API, specifying various initial intended recipients of a message, to check for the presence of certain identities in a public keyring. The compose dialog is displayed in the trusted UI, allowing the user to review and modify the list of recipients (only e-mail addresses are displayed). Upon encryption, a user can transfer the encrypted message and reviewed recipient list back to the web application. Potentially this allows the web application to extract unintended identities through the compose flow, but this attack would be visible to the user.

Public keys imported into the user's keyring are not exported into the keyserver. Public keys can be exported into a file by using "Export public key" or "Export keyring" functionality in the End-To-End settings page. We do not expose an API to web applications to export public keys.

Keys are stored in the extension's Local Storage. If the user has set a passphrase, the keys are encrypted. We use AES128 with a random per-installation salt and the string-to-key function uses SHA1 with 65,536 iterations. A SHA256 HMAC with a random IV is used to ensure integrity. Keys are never exposed to the web application or other extensions. We do not expose an API to export secret keys; they are not uploaded to Keyservers. However, Local Storage can be potentially accessed by Chrome Extensions able to use debugging APIs.

If an attacker inserts a secret key into the user's secret keyring, the user could then be accused of owning a given identity. As such, ownership of a secret key doesn't imply the user owns such an identity. To mitigate the threat of impersonation, secret key import to End-To-End requires user confirmation.

This threat is mitigated by providing the cryptographic operations using the End-To-End library designed to minimize timing side-channels. All secret key-based computations are performed in the extension background page, providing process separation from web applications (in Google Chrome, extensions are executed in a separate OS process).

An adversary might exploit a vulnerability in a cryptographic primitive or the protocol. We mitigate this threat in the following ways:

- End-To-End uses the standard OpenPGP (RFC 4880) protocol with the ECC extensions defined in (RFC6637).

- For random number generation, End-To-End uses cryptographically secure RNG (WebCrypto

getRandomValues). - End-To-End only generates ECC keys, and accepts keys with OpenPGP-compatible algorithms.

- All cryptographic code has been rewritten from scratch and reviewed multiple times. We do not depend on third-party crypto libraries.

- We use only chosen message digest, symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms. End-To-End rejects keys with weak key parameters. For example, RSA keys with moduli length < 1022 bits are rejected.

- All cryptographic code is open-source, subject to a public review.

- End-To-End is in-scope for the Google Vulnerability Reward Program that rewards security researchers for responsibly disclosing vulnerabilities. Two vulnerabilities have been reported and rewarded in the past.

Various Chrome Extensions and Apps can request debugging permissions that allow them to attach to an End-To-End background page, option page, or iframes, and execute code to exfiltrate or modify protected assets. We identified two dangerous APIs in that regard: Debugger API and DevTools API. Both of them allow an adversary to compromise End-To-End. Some of the potential security issues with Debugger API have already been addressed in the current Chrome version. We are aware of an attack vector allowing a malicious extension using DevTools API to run in a context of an End-To-End document, however this requires user interaction (opening DevTools). Unfortunately, from within the End-To-End extension we can offer no mitigations against this threat.

End-To-End code (or the code of its dependencies) may be backdoored to leak assets to an adversary. We mitigate this threat by open-sourcing End-To-End. All the dependencies used in End-To-End are also open-source. Additionally, any code added to the extension undergoes an internal peer review process.

The final version of End-To-End will be available on Chrome Web Store, signed with our internal developer key. Code signing prevents man-in-the-middle attackers from altering the code while it's being downloaded from the Chrome Web Store.

Extension source code and build tools are publicly available at our GitHub code repository. High-risk users may wish to download the code, build, and package the extension without relying on the build provided by the Google team, keeping in mind though that downloading the build toolchain may introduce additional risks. End-To-End is written in JavaScript with no binary code components, so the code can also be inspected client-side.

Additionally, we plan to add remote private key support in the future. When support for that is ready, high-risk users could protect their secret keys (stored, e.g., in a hardware USB device) from compromise even when an adversary introduces a backdoor in the source code.

An adversary might launch a denial-of-service attack against End-To-End using various vectors, e.g., by triggering decryption of large, compressed messages, import of large keyrings, blocking HTTP traffic, or abusing the Chrome messaging API. We do not mitigate this threat.