simplify your code, increase readability, become more productive. This is the first compiler built for the purpose of transpiling first.

Subscribe to our User's Mailing List | Subscribe to our Dev Forum

SMPL (pronounced "simple") is the compiler for the transpiling age. Using an easy to learn syntax, compile-time scope, and a command line interface, it allows you to build a dynamic and modular transpiler in minutes.

pattern { hello world } => {

return `console.log("hello world"); `

}

hello world //compiles to console.log("hello world");

SMPL is modular, lightweight, fast, and cool of course. It is built around an entirely new paradigm which is inspired by the rise of transpiling. By giving you the ability to create compile-time patterns and code, you are able to turn that confusing source code, into beatiful, idiomatic glory.

This is the first stable release. Please keep in mind that a lot has changed since previous versions.

- Getting Started

- Motivations

- Goals

- API

- The Compiler

- Syntax

- CLI

- Package Commands

- Standard Lib

- Compiler

- Source

- Changelog

- Roadmap

- Contributing

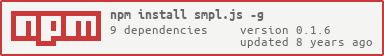

Simply install the package globally to get the command line tool

npm install smpl.js -g

smpl --help

It's in my belief that programming should not be hard. Programming languages, though they praise themselves on their buzzwords like "speed" and "concurrency", generally, one's ability to utilize these features becomes harder the more complex you make your program. And most of this problem is due to the fact that the underlying data model of your program has the ability to grow and change, but your ability to express this complexity remains stagnant. So, because of these limitations, [Programming Language X] Consortium decides they must boost their spec to meet the demands of their developers. And thus the slow cycle of spec releases and builds begins.

It's in my belief that we choose our programming languages based on the one that most closely fits the way we think and model things. It's obvious that the further away the semantics of your chosen language are from your natural thought patterns, the harder it will be to learn and apply.

All that aside, it cant be the job of the programming language to make things exactly to our individual liking. There has to be a way to modularize your libraries to "speak" like you do.

This was the motivation behind me wanting to build SMPL. The goal wasnt to make yet another parser/lexer/compiler. The idea is to create modules for your syntax, and use them to refactor, transpile, lint, or even build an entirely new language, with ease.

I've used libraries such as sweet.js and peg.js which were great, but fell short of what I was looking for. Mainly:

- Parsers like peg.js, language.js, or jison require you to build an entirely new programming language from scratch, using a syntax which, in my opinion, is more complicated then regex.

- Sweet.js has the right approach using macros, but its limited by forcing you to, well, use macros. All of your patterns are bound to a keyword, which makes more dynamic patterns harder to accomplish easily. Also, all that hygiene stuff makes my head spin.

- All of the current options make requiring npm modules to use in your compile a task that takes quite a bit of maneuvering.

- There is no way in any of these options to store arbitrary information into a compile time scope for use in other patterns and transformations.

These reasons and more make SMPL a perfect, and most importantly, easy solution for you.

SMPL doesn't try to be a full on compiler. There are some things that they may, quite frankly, do better. However, SMPL's goals help outline our approach for the future of this project.

- Easy Syntax

- Small Footprint

- Easy Interface

- A Package Ecosystem

- An Open Community

- Fun

Go to our Goals Page in the wiki to learn more about each of these.

SMPL, amongst other things, have made tremendous effort to simplify the process of compiling/transpiling. Thus we've given you a very simple syntax to construct your own grammars.

Knowing about the compiler isn't necessary, but it helps you understand whats going on when you are building your patterns. Each pattern is essentially a special tokenized version of regular expression. They can have a name, a priority, and a transform (more about each below) .

Each round of the compile loop, checks each pattern to see if there is a match in the document. the match whose position is closest to the cursor will advance the cursor to its position, then will fire the appropriate transform context. The context is given a result object which contains the matched string, and properties mapping to those found in the pattern template.

Patterns must return a string or string-like object. Patterns which do not return a result (false, null, or undefined), will be excluded from all the following cycles, until a match is found for another pattern-- then the excluded pattern will be returned to the compile loop.

Patterns which return a result, will replace its match in the input string, and progress the cursor to after the appearance of the replacement.

Every pattern must contain a template, with which it can perform its matches. A Pattern template is surrounded by {} curly braces, and utilize variables, classes, and repeats to express your desired logic. Below is the most basic form of a valid pattern:

{ hello world }

It matches the appearance of the literals "hello" and "world".

You'll obviously want to do much more than match inputs literally. For more dynamic features, pattern variables are needed.

The pattern variable gives you the ability to store pieces of the match, into properties of the context of the pattern's transform. It is denoted by a $ dollar sign followed by a literal. i.e. $VarName

A pattern variable must be declared with a variable class. variable classes are denoted by a : colon and the name of the class. More on that below.

In total, when using a pattern variable, it should look like this.

{ I am $age:num years old }

//$age is our variable

//num is our class, which in this case represents a number class.

This will match an input such as I am 10 years old where 10 would be stored into our variable age

The variable class, as stated above, represents a primitive which can be used in your match. There are 9 classes in total.

stra string, denoted using either''""or``characters.numany positive or negative whole integer.9-90187912floa float type integer with an optional decimal point10.11001423.32litan identifier constructed of legal alphanumeric characters and symbolsnamecamelCaseunder_scoredm1x3d_numb3rpuncpunctuators that are not also operators.,:?!;opmath operators+*^%&delimdelimiters()[]{}symother miscellaneous symbols#$~@bracketa special class for matching nested brackets{...}

Mix and match these to create powerful and dynamic patterns.

Repeats can cause some unexpected results and performance costs when dealing with nested structures like brackets. To combat this, we have created a special bracket class that makes some smart decisions based on the context of the pattern it is being placed in. Always use the bracket class when trying to match repeating brackets

{...},{...},{...}

Variables and Classes must always be paired together, except for when you use a repeat, denoted using a ... ellipses after your variable. A repeat can mean different things depending on how you use it. The simplest form is to merely attach it after a literal.

{hello... world}

this will match hello hello hello hello world. But that's not very fun. If you want to make something a bit more dynamic with you repeats, initialize it with a variable.

{ hello $adjectives... world }

This will first match hello then match anything until it reaches the first appearance of world. i.e. hello beautiful, amazing world

If you want to be more specific with what is repeating, it uses a slightly different syntax. If you want to specify a particular class to repeat, declare your pattern var $var:class and proceed it with a () parenthesis then your repeat. Inside the parenthesis goes a delimiter such as ,, which separates the class.

{ hello $adjs:lit(,)... world }

This will match hello beautiful, amazing, SIMPLE world . Note, the delimiters only match between the literals and there are no leading or trailing commas.

delimiters can be absolutely anything, even an entire sentence.

{ $count:num(bottles of beer on the wall)...}

This would match 99 bottles of bear on the wall 98 bottles of beer on the wall 97 bottles of beer on the wall...

When using delimiters which encapsulate values

()[]{}, variables, and repeats in conjunction, space can affect the meaning of your pattern. Placing space between the delimiters and the repeat like,( $match... )it performs a non greedy match to the first appearance of the closing brace. If there are no spaces($match...)performs a greedy match, until the number of open braces matches the number of closing braces.

/ ** Given **/ ( a ( b )( c) )The former pattern would match(a(b)while the latter would match the entire object( a ( b )( c) )

For instances where you want to match a complex pattern without declaring a separate pattern, pattern groups are you companion. They are initialized also using the $ symbol then proceeded by your pattern enclosed in () parenthesis.

{ hello $( $place:lit ) }

Pattern groups act like a variable, meaning you can use it in repeats in much the same fashion.

{ hello $( $place)(,)... }

Results matched from a pattern group get placed inside the group variable of your context, and denoted by a index number 0-n that represents the order which it appeared in your pattern.

It's important to note, that whitespace is not matched literally as it appears in your pattern. Every time there is whitespace detected in your pattern, it is counted as 0 or more spaces.

{ hello world }

//matches hello world

//hello world

/*

hello

world

*/

Also keep in mind that whitespace is a character, in fact, it even has its own secret character class $var:whitespace. You'll probably never have a good reason to use the class, which is why it's not written in the pattern class section, but, why this is important is because when doing repeats, and empty () or the equivalent ( ) are valid delimiters.

When a pattern template has been matched against, the result is applied to the context of your transform function. It can be accessed via the this keyword or by simply calling the name of your variables directly within the context. The syntax used within the context of your transform is javascript. Any value you wish to replace with your match, you would return from the context. A transform context is also denoted using the {} curly braces.

pattern { hello world } => {

//transform context

return "goodbye planet"

}

more on pattern declarations later

Any variables declared in the pattern will be applied to a variable of the same name, minus $ dollar sign, in the context.

//patterns.smpl

pattern { hello $place:lit } => {

return this.place;

}

pattern { hello $place:lit } => {

return place; //these are functionally equivalent

}

pattern { goodbye } => { return this //contains the entire match } //hello-world.js

hello world //returns world;

goodbye //returns goodbye (no change)All variables called within a group, can be found in the groups array by the index it is found in the template.

pattern { hello $( $place:lit ) } => {

return groups[0].place

}

This will execute in the same fashion as the examples above.

Nested named patterns will nest objects as you'd expect.

pattern place { $city:lit , $state:lit } => { return null }

pattern { hello $place:place } => {

return place.city;

}

hello baltimore, md //evaluates to baltimore

as you can see, city is a property of place as we've defined it.

In addition to giving you an objectified version of your pattern as context variables, you are also given access to a global scope. In the current version, scope maintains state between files in a single call to compile from the CLI. The scope contains a set of functions and objects provided to you by the compiler to help you create more dynamic patterns, as well as access to variables defined in compile time code-blocks. be aware that in the transform context, although you can get and mutate values already defined on the scope, you do not have the ability to declare new variables on the scope. All variables declared in the transform context are locally defined

The compiler provides you with the following variables:

compilergives you access to the raw compiler object and all of its methods

And the following methods:

compile( input:str )runs a local compile of the provided input. (meta!!!)addPattern( template,:str, transform:funct, options:obj)manually adds a pattern to the compiler. (more in Standard Lib section)prepend( input:str )prepends the provided string, uncompiled, to the top of your compiled document.append( input:str )appends the provided string, uncompiled, to the bottom of your compiled document.unpend( input:str )deletes all appended and prepended strings.

The entry point to developing your compiler is a pattern declaration. It tells the compiler what you would like to match, and how you would to match it by combining pattern templates with transform contexts.

The easiest and most basic form of a declaration is a standard one. It is denoted using the pattern keyword followed by a template, => operator, then a transform.

pattern { hello world } => { return `console.log("hello world")` }

//keyword -> template -> op -> transform

The above pattern will read in an instance of hello world and replace it with console.log("hello world"). The form of declaring patterns is powerful in that it allows for mutations and conditionals to happen in the body, and return dynamic results.

pattern {hello $place:lit } => {

if( place == "world" ) return `hello(${place})`

else return `greetings("${place.replace("b","B")}")`

}

hello world //compiles to hello(world)

hello baltimore //compiles to greetings("Baltimore")A named declaration allows you to reference the pattern in another pattern by name. The syntax is similar to a standard declaration, with the exception of placing a lit between the pattern keyword and the template.

pattern hello { hello world } => { return `console.log("hello world")` }

//keyword ->name -> template -> op -> transform

The above pattern is functionally equivalent to declaring it without its name, however, now it can be referenced by another pattern.

pattern age { $age:num years old } => { return age }

pattern { I am $age:age } => {

return `{ age: ${age.transformPattern() }}`

}

I am 12 years old //compiles to {age:12}Notice the use of the method transformPattern(). This method is used to perform local transforms of a matched pattern. In this case, the variable age before we transformed it, contained 12 years old. By calling the method, it calls the transform context which you defined for the age pattern.

pattern age { $age:num years old } => { return age }

pattern { I am $age:age } => {

return `{ age: ${age.T() }}`

}

I am 12 years old //compiles to {age:12}T() is an alias for transformPattern().

If you need multiple patterns to be classified under a single name, use the alternation syntax. This will take a group of templates and test against the first to match. it is declared the same as a standard or named pattern, but rather than providing a single pattern template, you give it an array denoted using [] square brackets, and your templates comma separated inside.

pattern [{...},{...},{...}] => { ... }

pattern name [{...},{...},{...}] => { ... }As they use alternation, and require a more elaborate construction, there is a slight performance cost to using these. use sparingly and try to use variables to acheive the same result where possible

Notice also that they operate on a single context, so patterns with differing set of variables must undergo a conditional check to get desired results.

pattern hello [{hello world},{hola mundo},{gutentag $worldWord:lit}] => {

if(this.worldWord) return `hello(translate('${worldWord}'))`

return "hello('world')"

}

hello world //hello("world")

gutentag blahblah //hello(translate('blahblah'))If you wanted to create a pattern that matches, but there is no need for any transform logic, use the class declaration. Its similar to declaring a named pattern, but without the transform parts.

class name {...}

class name [{...},{...},{...}]

This is functionally equivalent to declaring a pattern that returns null, except that it comes with a performance boost to the compiler. Since it doesnt have a transform context, the compiler doesnt even consider it for a match in the loop. Classes are merely used for referencing patterns in others by passage of a variable.

Use as much as possible. Patterns which return null, albeit performing the same task, causes the compile loop to take an additional cycle to negate it. By using a class, it isnt even considered, thus saving resources. (read the compiler section for more on the compile loop).

This is, by far, the most stand-out feature that SMPL provides. The capture declaration allows you to declare a pattern that not only operates like a normal pattern, but also gives you a new setter method addCapture() for adding alternations to a special form of the pattern, which can be used in other patterns.

The best way to illustrate this is through demonstration

capture var { var $name:lit } => {

addCapture(name);

}

pattern { $object:$var $props:lit()... } => {

return `${this.object}.${this.props.join(".")}`

}

boy name first //compiles to boy name first

var boy = {

name: {

first: "john",

last: "smith"

}

}

boy name first // compiles to boy.name.firstNotice that although the capture is declared with var as a name, it is referenced using $var. This is because the pattern var is the pattern which you've declared for the capture ({var $name:lit}). So if you did this instead.

pattern { $object:var $props:lit()... } => {

return `${this.object}.${this.props.join(".")}`

}

var boy = ...

boy name first // compiles to boy name first

var boy name first //compiles to var boy.name.firstYou'll notice it doesnt match things as you'd expect. The compiler will lookup your capture template directly, and use that to match against -- which will subsequently add another instance of boy to the captures list. The values you place into addCapture are stored, instead in the $ affixed version of the captures name.

addCapture( pattern:PatternTemplateString)add capture takes a single input, a pattern template. However, inside the context of the transform, pattern templates must be given in the form of a string.

There are times when you need to create global variables, or require other libraries into your compiler. Adding other npm modules, especially, can be very handy in making your compiler seem almost magical. Code blocks are initialized by surrounding your block with ---.

// .\examples\language_features

--- //code-block

prepend("var Color = require('color');");

unpend();

---

capture colors [{ color $name:lit = $value:str },{ color $name:lit = $value:flo }] => {

this.addCapture(this.name);

return ` var ${this.name} = new Color(${this.value})`;

}All variables declared in a code block are locally bound. If you would like to create a global variable, for use in patterns, use the ctx keyword instead.

--- ctx sweet = require("sweet.js"); ---

pattern { $program... } => {

sweet.compile(program); //compiler-in-compiler. INCEPTION!

}Variables declared using the ctx keyword are shared between all documents in a given compile.

NOTE because files given to the command line tool can compile in any order, it is wise that you do any variable declarations in a module, rather than in-document. This will ensure that all the documents receive the variable and its not missing from the context of any unexpectedly.

Once you have constructed your documents, use the command line tool to compile it into your target language. you start with prompt smpl

compile is your entry point. you can simply use the smpl compile command along with input glob to parse your files.

$ smpl compile ./example/*.example

optionally you can use c or p

$ smpl c ./example/*.example

this will simply compile your file into a javascript file in the same directory. You can also optionally specify different options to alter your results.

You can use the extension's flag to change the file type of your outputs

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -e .cpp

will output a c++ files from your .example's

Specify an output directory

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -o ./build

Sometimes you may want to separate your patterns from your working documents. If you have done that, you can specify the document with your patterns using the -m flag

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -m patterns.js -o ./build

if you would like your output to be in a single file, use the -c flag to join them together.

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -c example.js -o ./build

If you would like to watch a file or directory, place the -w flag in the query.

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -o ./build -w

If you dont want to compile it to a file, but want to run the file in the terminal instead (given that the resultant file is javascript), use the -r flag.

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -o ./build -r

-d outputs log messages to help you figure out where something may be going wrong.

$ smpl c ./example/*.example -o ./build -w

Use the help flag after any argument to get an overview of all of the arguments you can use.

$ smpl --help

Invalid Command. Showing Help:

Commands:

help [command...] Provides help for a given command.

exit Exits application.

compile [options] <dir> Parses the files at the given directory (node glob)

You can optionally add commands to your package.json file. smpl will read your package for the "smpl" object, and parse any expressions that you make a key for.

"name":"my_package",

...

"smpl": {

"examples": "c ./examples/**/*.smpl"

}

This will allow you to call commands without the need for the long query strings

$ smpl examples

//same as

$ smpl c ./examples/**/*.smpl

- modified pattern template syntax

- added functional transform context

- added class type pattern

- added

-rflag - added new examples

- modified core parser.js

- added new cursor with line and column information.

- added compile-time code blocks and scope

- Compiler bound patterns (patterns which can use other patterns within its transform context)

- Numeric Priority for patterns. More precise matches.

- Modify captures list

- web component for react, angular, polymer, & html5 for testing without having to compile.

- SPC - SMPL Package Control or "space", a customized package manager for SMPL modules.

- Faster Compile times

- Custom string matcher to replace regexp

- Smaller File Sizes.

- Less Dependencies