In a programmable space the concept of a computer is expanded outside a little rectangular screen to fill the entire room. Interacting with the programmable space means using physical objects, not virtual ones on a screen. Bringing computing to the scale of a room makes it a communal and social experience.

The idea of a programmable space is an ongoing area of research by Jacob Haip, an independent researcher based in Boston, USA.

- Backstory

- Project Overview

- Gallery

- Setting up your own programmable space

- Getting Involved

- Inspirations

Today people can do almost everything on a computer, but "using a computer" means staring at apps on their own little rectangular screens. This is sad because it makes people tired of screens, antisocial, reduces people to button clicks, and convinces people that they "aren't good with computers".

How can we change the affordances of using a computer so that they are more humane and inviting? Computers demand all your foreground attention in a fixed position. How can we take advantage of periphery senses and the full body capabilities of people? Computer GUIs cram so much information in screens behind layers of menus and pages when there is so much space in the world! How can we take advantage of all the space in the room? People consume apps and don't feel empowered to do much besides download a better app. In some ways this makes sense when the barrier to making something new is so formal. How can we make editing the tools you use a normal and easy part of using a computer?

We explore these ideas in a long term research project under the name "programmable spaces". We seek to create a system that is:

- Gradual

- Room-scale

- Multiplayer/social

- Always-on

- Editable and understandable

Most research so far has used the idea that computer programs have a 1-1 mapping with physical objects. Physical objects have the source code written/printed on them so people in the room can read what the code does. There is no use of traditional GUI computer interface - everything is remade in the room.

Click here to see an example of a minimal programmable space that uses RFID cards as the physical representation of programs.

A programmable space is the combination of two parts:

- What the physical objects are, how people interact with them, and how they can be used as inputs to the system

- The software implementation that brings the system to life. This defines the semantics of the code, what is possible for people in a programmable space, and how it can be implemented on existing computer systems.

The code in this Github project covers the software implementation. The physical side is described in this README and is illustrated in the Gallery.

Research so far has used the idea that program source code is printed on physical objects in the room. Although this research explores more physical ways to make and mold systems, I don't imagine a world that is totally free of text and building on existing textual programming languages is a convenient starting point.

Therefore there are two main types of physical objects:

- Physical representation of code

- Auxillary physical objects used to make the system more tangible: motors, sensors, game controllers, keyboards, printers, ...

Two types of physical representations of code have been tested:

Inspired by the papers of Dynamicland, programs are represented by pieces of paper with source code and colored dots printed on it. The printed source code is so people in the room can understand what the program does. The colored dots are so a camera and computer system can identify and understand what the program does.

Each paper has four sets of colored dots in each corner. Four different colors are used for the seven dots in each corner. Each corner can uniquely identify the papers, but 3 or 4 corners are needed to get the size and orientation of a paper. A program takes in webcam images, processes them with OpenCV, and then claims what and where papers are located in the room.

The middle of the paper is also a nice canvas for projecting graphics onto the paper. The projector and camera can be calibrated together to enable projection mapping wherever papers are put in the room. Having a mini display for every program is fun and helpful.

- Pros: Takes advantage of how common 2D printers are. Programs can be sensed in any orientation. Papers can be cut and made different sizes. Supports dynamic projection mapping well.

- Cons: Camera systems have occlusion and lighting issues.

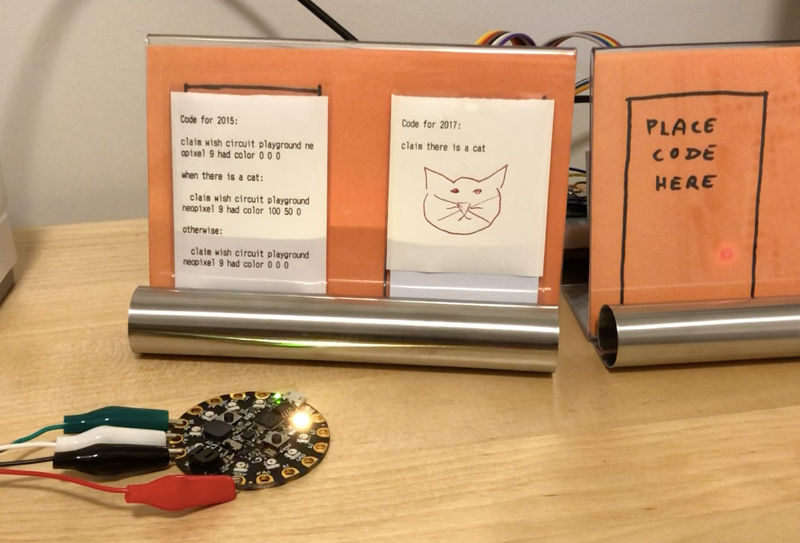

Programs are represented by standard RFID cards with printed source code attached to it. Most commonly, I have printed source code using a receipt thermal printer and used a plastic trading card case to hold both the RFID card and the receipt paper. Another variant I have tried is taping RFID cards to the back of clipboards that hold full size papers with printed source code.

The RFID cards are sensed by RFID readers. RFID sensors can only sense one card at a time and cards must be placed directly on top of the sensor so a separate sensor is needed for every program. For example, two RFID sensors can be hidden behind an angled photo frame:

- Pros: No occlusion or lighting issues. RFID cards are durable. Trading card size is nice to hold.

- Cons: Can't detect orientation. Cards can only be placed on the fixed locations of RFID sensors. More expensive to scale. Projection mapping requires more calibration.

Behind the scenes, the pieces of code with a 1-1 mapping to physical objects run on computers as normal Operating System processes. Users do not use a normal computer GUI directly, and so many low-level actions such as running programs, editing programs, printing, graphical displays, sound, etc. are remade in the physical context of the room. There is a core group of "boot programs" that form the "Operating System" layer that support all the other programs in the room.

Each process connects to a broker that manages communication within the system. The broker manages the "fact table" and communication between processes. The processes themselves handle the sensing of physical objects and all other functionality of the system.

The core software idea is that the room has a shared list of "facts" that things within the room use to communicate.

Fact = Typed list of values that reads like a sentence

Soil moisture is 50.3

[text] [text] [text] [number]

Fact Table = Shared list of all facts from objects in the room

Fact 1. Soil moisture is 50.3

Fact 2. Light should be off

Fact 3. Time is 1600909276

Programs can update the Fact Table in two ways: Claim or Retract.

Claim = Add a Fact to the Fact Table

Claim(Soil moisture is 50.3)

Retract = Remove facts matching a pattern from the Fact Table

// fully specified fact

Retract(Soil moisture is 50.3)

// $ is a single wildcard value of any type

Retract(Soil moisture is $)

// % is a postfix wildcard that matches until the end of the fact

Retract(Soil moisture %)

Programs can listen for changes to the fact table to influence their own actions via Subscriptions.

Subscription = A program's desire to get updates from the Fact Table about Facts that match a pattern. The pattern is specified as a list of typed lists. Patterns follow Datalog rules where reused variables must match in each result.

Given the fact table

Fact 1. Sensor sees red Fact 2. Light should be off Fact 3. red is Jen favorite color Fact 4. blue is Smo favorite colorExample subscriptions and results:

Light should be $value --> 1. value = offtoday is $day --> No resultsLight should be off --> 1. (one result but no values)$color is $person favorite color --> 1. color = red, person = Jen 1. color = blue, person = SmoSensor sees $color, $color is $person favorite color --> 1. color = red, person = Jen

The Fact Table is maintained by a broker.

Broker = Software system that objects and programs talk to that manages updates to the Fact Table and informs subscribers about changes. All Claims, Retracts, Subscriptions, and Subscription Results flow through it.

The Broker also performs helpful things like

- Saving a prior history of facts for new subscribers

- Performance critical code to calculate subscription results

- Consolidating Datalog query logic

The shared fact table is used as a communication mechanism between programs for this project because it:

- Allows the people writing programs to claims facts and subscriptions that read like a sentence.

- Allows programs to communicate asyncronously without needing to know about other programs.

- Maps well to the idea that programs in the same physical space share common knowledge.

When a program is stopped, all the facts and subscriptions it made in the shared fact table are removed. This keeps the shared fact table relevant only the programs that are currently visible in the room and running. Additionally all facts in the shared fact table record what program claimed the fact so the same fact claimed by two different programs is considered two unique facts.

The broker should be "local" to the programs in the room and only serve about as many programs that can fit in a single "space" or "room". For larger spaces or to connect multiple rooms together, facts can be explicitly shared to other brokers and computers. In this way data and programs are federated. Federation is useful both technically (because a single broker cannot hold all the facts in the universe) and to aid in the understanding of the people working in a space. For example, the position of a paper on a table is very important to someone reading the paper at the same table, but the position of a paper in a different room is irrelevant unless the person at the table has some special reason they care about something going on somewhere else.

Programs have been implemented in multiple programming languages (Python, Node.js, Golang, Lua, an experiemental custom langauge). The bidirectional communiation between programs and the broker is handled via Websockets.

- CircuitPython Editor. 2021-04-25

- Musical Posters. 2020-08-29

- Voice Assistant reimagined. 2020-07-15

- Recreation of the "Dangling String". 2020-04-03

- Calendar on wall and input and output using laser pointer and projector desk lamp. 2020-03-25

- Turtlebot simulation using cards as input parameters. 2020-03-10

- Desk lamp with projector inside used as output. 2020-02-16.

- Programs represented by RFID Cards and receipt paper. 2020-02-11

- Animated drawing from papers on desk. 2019-09-26

- Defining and interacting with regions on wall with a laser pointer. 2019-09-08

- Non-textual programming of robots. 2019-09-08

- Using spatial arrangement of dot papers. 2019-09-08

- Putting code onto microcontrollers. 2019-03-17

- Programs represented by RFID Clipboards. 2019-03-17

- Fixed 3x3 grid of programs + text editor. Projected on wall but no camera sensing. 2019-01-20

Every space is different and should be built to fit the needs, experience, and goals of the people that work within it. A programmable space is not an app you download and run, but something that should be built by you. But spaces do have similar baseline needs:

- A way for humans and computers to understand what programs are running and which are not.

- Some sort of display that running programs can use for visual feedback

- A way to edit programs and create new programs

After deciding on a way people will know what programs and running and which are not, an appropriate sensor can be chosen to detect that. For example if a program is represented by a piece of paper with code on it, then a running program could be when it is face-up and visible to everyone in the room. A sensor that could be used to detect face-up papers is a camera.

The easiest way of physically representing code is with papers with colored dots so I recommend starting there. This guide will assume you have a webcam and a projector to do projection mapping, but you could use a webcam and an alternative display like a computer monitor if you don't have a projector. A more immersive experience can be made by putting the cameras and projectors in the ceiling, but to begin with I'll assume you are pointing the projector and camera at a wall. A magnetic whiteboard is a nice way to attach papers to the wall, but I have also used painter's tape.

-

A computer. Preferrably running Ubuntu but I have also done some work on MacOS. It could be a cloud server but for things that happen locally to a room it makes a little more sense to keep the networking local.

- Currently I'm using a Intel NUC mini PC with 16 GB RAM, a quad-core Intel i5 at 1.30GHz, and a SSD. 16 GB RAM seems to be excessive in my tests but having multiple cores are important when many programs are running.

-

For camera sensing of papers: a webcam. I use the Logitech C922 to get HD video at 30fps.

- Some way to mount the webcam

-

When using a projector as a display: Any projector should work but HD projectors are nice when projecting small text. Projectors with higher lumens will make the projected graphics more visible in daylight. I used the Epson Home Cinema 1060 when projecting across the room and the Optima GT1080 short throw projector when projecting down at a coffee table or the ground.

- Some way to mount the projector

-

A generic color 2D printer for printing the papers that represent programs.

-

Magnetic whiteboard or painters tape to attach papers to the wall

-

A computer monitor or TV as a supplemental display.

- A monitor is useful when starting the computer and when debugging

Arrange the webcam and projector so that the webcam can see all of the projection area and a little more.

Operating system:

- Tested with Ubuntu 16.04

- Partial tests with MacOS High Sierra

Golang:

- For the broker and a few core programs

- Golang 1.12+

- Dependencies are tracked in the

broker/go.modfile and will be automatically downloaded and installed when running a Go program for the first time. - When building the Go files, you may need to copy the

broker/go.modandbroker/go.sumfiles to the root folder of this repo in order for thesrc/programs/Go files to be build properly.

Node.js:

- Used for boot programs and most regular programs

- Node.js v10.6.0

npm install

Python:

- Used for some boot programs and some special regular programs that have nicer Python libaries than Node.js libraries

- Python 3.5+

pip3 install -r requirements.txt- For camera sensing: OpenCV 3.4

- For UI of

1600and1700: wxPython4 - For playing MIDI sounds

777and capturing keyboard input648pyGame 1.9.5+

Processing for graphical output:

- Install Processing 3 from https://processing.org/

- Then install the Video library by opening Processing and going to "Sketch" > "Import Library" > "Add Library".

Printing Papers:

lprwith a default printer configured.

Lua/Love2D:

- Used for graphical output

src/programs/graphics.lua sudo apt install lua5.1sudo apt install love(for love 2d)sudo apt install luarockssudo apt install libzmq3-dev- Install https://github.com/zeromq/lzmq

sudo luarocks install lua-llthreads2sudo luarocks install lzmq

sudo luarocks install uuidsudo luarocks install lua-cjson

For moving windows around programmatically sudo apt install xdotool is needed.

When installing on a Raspberry Pi these addition things may need to be installed when running the computer vision:

sudo apt-get install libhdf5-dev sudo apt-get install libhdf5-serial-dev sudo apt-get install libcblas-dev sudo apt-get install libatlas-base-dev sudo apt-get install libjasper-dev sudo apt-get install libqtgui4 sudo apt-get install libqt4-test sudo apt-get install libczmq-dev sudo apt-get install libqtgui4

In this demo, programs are represented by printed ArUco markers taped to pieces of paper. The ArUco markers are detected by the 1631__arucoTagCv.py program that processes frames from a webcam.

- Print out ArUco tags (from the 6x6 dictionary) and tape them to papers to represent programs using aruco-grid-print.html or https://chev.me/arucogen/ . I keep a pile of blank cards on the table ready to be made into programs.

- Set up the webcam to point down at a table (or at a wall) where the paper programs will be.

- Run

./jig arucostart. This starts the broker and112__arucoEditorBoot.js- This starts a few key programs that deal with running programs, editing programs, debug views, the ArUco CV program (1631), and the ArUco to program web manager (1636, running at

localhost:3023)

- This starts a few key programs that deal with running programs, editing programs, debug views, the ArUco CV program (1631), and the ArUco to program web manager (1636, running at

- Open

localhost:3000in your browser to see the broker's fact table

- Associate ArUco cards to programs at

localhost:3023 - Make a card for 1014, a web text editor:

- print out an ArUco marker and tape it to a piece of paper

- write "1014 Web Editor" on the paper

- Place that paper and marker where the webcam can see it

- Make a card for 1246, a web graphical output and place it in view of the webcam

- Make a hello world card:

- Create a new program using the 1014 web editor at

localhost:3020 - Put in this code:

const { room, myId, run } = require('../helpers/helper')(__filename); let ill = room.newIllumination() ill.fontcolor(255, 0, 0); ill.text(0, 0, "Hello World!") room.draw(ill); run(); - Save

- Print out an ArUco ID and tape it to a paper. Write "hello world" on it. You'll need to know the ID of the aruco card.

- Open

localhost:3023to associate the aruco card ID to the program you just created. - Open

localhost:3012to view the web graphical output. - Now when you place your card on the desk, it should show hello world. When you remove the card, it shows it.

- Create a new program using the 1014 web editor at

- Associate 1014__webEditor.js to an aruco card and place that card on your desk.

- Edit, create papers, and print papers at

localhost:3020 - For new programs, you'll need to associate them to an aruco card at

localhost:3023after saving.

Read more about source code editing here.

Debugging:

- Open

localhost:3000in your browser to see the broker's fact table ./jig logto see the broker logps aux | grep programs/to see what programs are runningtail -f src/programs/logs/YOUR_PROGRAM_NAME.logto see the logs from a particular program.

As this is an informal and long-term research project, we invite everyone to make their own programmable spaces and share their thoughts. A programmable space is not an application that can just be downloaded to a computer, but this Github repository contains a broker and an example set of programs that is a good starting point for your own programmable space. Fork this repository and make pull requests if you would like to suggest an improvement.

An even more important way to contribute to this project is to build a programmable space system that is valuable to the people around you and then share your findings. What were people empowered to do? What new types of challenges were found in trying to move a computer system into the physical world? What types of edits and usage cases were valuable to the people in your space?

- Dynamicland

- "Living Room" project @ Recurse Center

- Phidgets: easy development of physical interfaces through physical widgets. UIST 2001

- Tangible Bits: Towards Seamless Interfaces between People, Bits, and Atoms. CHI 1997