Dependency injection framework for go programs (golang).

DI handles the life cycle of the objects in your application. It creates them when they are needed, resolves their dependencies, and closes them properly when they are no longer used.

If you do not know if DI could help improve your application, learn more about dependency injection and dependency injection containers:

There is also an Examples section at the end of the documentation.

DI is focused on performance.

A definition contains at least a Build function to create the object.

MyObjectDef := &di.Def{

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

// It is possible to add a name or a type to make the definition easier to retrieve.

// But it is not mandatory. Check the "Definitions" part of the documentation to learn more about that.

MyObjectDef.SetName("my-object")

MyObjectDef.SetIs((*MyObject)(nil))The definition can be added to a builder with the Add method:

builder, err := di.NewEnhancedBuilder()

err = builder.Add(MyObjectDef)Once all the definitions are added to the Builder, you can call the Build method to generate a Container.

ctn, err := builder.Build()Objects can then be retrieved from the container:

// Either with the definition (recommended)

ctn.Get(MyObjectDef).(*MyObject)

// Or the name (which is slower)

ctn.Get("my-object").(*MyObject)

// Or the type (even slower)

ctn.Get(reflect.typeOf((*MyObject)(nil))).(*MyObject)The Get method returns an interface{}. You need to cast the interface before using the object.

The container will only call the definition Build function the first time the Get method is called. After that, the same object is returned (unless the definition has its Unshared field set to true). That means the three calls in the example above return the same pointer. Check the Definitions section to learn more about them.

You need a builder to create a container.

You should use the EnhancedBuilder. It was introduced to add features that could not be added to the original Builder without breaking backward compatibility.

You need to use the NewEnhancedBuilder function to create the builder. Then you register the definitions with the Add method.

If you add two definitions with the same name, the first one is replaced.

builder, err := di.NewEnhancedBuilder()

// Adding a definition named "my-object".

err = builder.Add(&di.Def{

Name: "my-object",

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{Value: "A"}, nil

},

})

// Replacing the definition named "my-object".

err = builder.Add(&di.Def{

Name: "my-object",

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{Value: "B"}, nil

},

})

ctn, err := builder.Build()

ctn.Get("my-object").(*MyObject).Value // BBe sure to handle the errors properly even if it is not the case in this example for conciseness.

It is only possible to call the EnhancedBuilder.Build function once. After that, it will return an error.

Also, it is not possible to use the same definition in two different EnhancedBuilder.

And you should not update a definition once it has been added to the builder.

All these restrictions exist because the EnhancedBuilder.Build function alters the definitions. It resets the definition fields to their value at the time when the definition was added to the builder. Thus the definitions are linked to the builder and to the container it generates.

A definition only requires a Build function. It is used to create the object.

// You can either use the structure directly.

&di.Def{

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

// Or use the NewDef function to create the definition.

di.NewDef(func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

})The Build function returns the object and an error if it can not be created.

panics in Build functions are recovered and work as if an error was returned.

The Build function can also use the container. This allows you to build objects that depend on other objects defined in the container.

MyObjectDef := di.NewDef(func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

})

MyObjectWithDependencyDef := di.NewDef(func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

// Using the Get method inside the build function is safe.

// Panics in this function are recovered.

// But be sure to add a name to the definitions if you want understandable error messages.

return &MyObjectWithDependency{

Object: ctn.Get(MyObjectDef).(*MyObject),

}, nil

})You can not create a cycle in the definitions (A needs B and B needs A). If that happens, an error will be returned at the time of the creation of the object.

You can add a name to the definition. It allows you to retrieve the definition from its name.

// Create a definition with a name.

MyObjectDef := &di.Def{

Name: "my-object",

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

// The SetName method can also be used.

MyObjectDef.SetName("my-object")

// Retrieve the definition from the container.

ctn.Get("my-object").(*MyObject)If you do not provide a name, a name will be automatically generated when the container is created.

Retrieving an object from its name instead of its definition requires an additional lookup in a map[string]int. That makes it significantly slower. If performance is critical for you, you should retrieve objects from their definitions.

Another advantage of using the definitions for object retrieval is that it avoids the risk of a typo in the name.

The drawback is that you need to import the package containing the definitions which may lead to import cycles depending on your project structure.

There is a shortcut to create a definition for an object that is already built.

MyObjectDef = di.NewDefFor(myObject)

// is the same as

MyObjectDef = &di.Def{

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return myObject, nil

},

}By default, the Get method called on the same container always returns the same object.

The object is created when the Get method is called for the first time.

It is then stored inside the container and the same instance is returned in the next calls.

That means that the Build function is only called once.

If you want to retrieve a new instance of the object each time the Get method is called, you need to set the Unshared field of the definition to true.

MyObjectDef = &di.Def{

Unshared: true, // The Build function will be called each time.

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

// ...

// o1 != o2 because of Unshared=true

o1 := ctn.Get(MyObjectDef).(*MyObject)

o2 := ctn.Get(MyObjectDef).(*MyObject)A definition can also have a Close function.

di.Def{

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

Close: func(obj interface{}) error {

// Assuming that MyObject has a Close method that returns an error on failure.

return obj.(*MyObject).Close()

},

}This function is called when the container is deleted.

The deletion of the container must be triggered manually by calling the Delete method.

// Create the Container.

app, err := builder.Build()

// Retrieve an object.

obj := app.Get("my-object").(*MyObject)

// Delete the Container, the Close function will be called on obj.

err = app.Delete()It is possible to set the type of the object generated by the Build function.

It is only declarative and no checks are done to ensure that this information is valid.

It can be used to retrieve an object by its type instead of its name.

You can set multiple types, for example, a structure and an interface implemented by this structure.

MyObjectDef = di.NewDefFor(myObject)

// Declare that myObject is an instance of *MyObject and implements MyInterface.

MyObjectDef.SetIs((*MyObject)(nil), (MyInterface)(nil))

// ...

// Retrieve the object from the types.

ctn.Get(reflect.TypeOf((*MyObject)(nil))).(*MyObject)

ctn.Get(reflect.TypeOf((MyInterface)(nil))).(MyInterface)It is possible to use the NewBuildFuncForType function to generate a Build function for a given structure (or pointer to a structure). When the object is created using reflection, it will try to set the fields based on their types and the other definitions. There is also a shortcut NewDefForType to create a definition based on NewBuildFuncForType.

// Definition for an already built object, declared having the type *MyObject.

MyObjectDef = di.NewDefFor(myObject).SetIs((*MyObject)(nil))

// The definition can create a *MyObjectWithDependency

// and the MyObjectWithDependency.Object field will be filled with an object

// from the container if there is one with the same type.

// NewDefForType does not set the type of the definition. You need to call SetIs yourself if you want to.

MyObjectWithDependencyDef := di.NewDefForType((*MyObjectWithDependency)(nil))

// ...

// o1 == o2

o1 := ctn.Get(MyObjectWithDependencyDef).(*MyObjectWithDependency).Object

o2 := ctn.Get(MyObjectDef).(*MyObject)Build function makes it very slow. The behavior of the NewBuildFuncForType may also change in the future if ways to improve the feature are found.

You can add tags to a definition. Tags are not used internally by this library. They are only there to help you organize your definitions.

MyObjectDef = di.NewDefFor(myObject)

tag := di.Tag{

Name: "my-tag",

Args: map[string]string{

"tag-argument": "argument-value",

},

Data: "Data is an interface{} if Args are not enough",

}

MyObjectDef.SetTags(tag)

MyObjectDef.Tags[0] == tag // trueWhen a container is asked to retrieve an object, it starts by checking if the object has already been created. If it has, the container returns the already-built instance of the object. Otherwise, it uses the Build function of the associated definition to create the object. It returns the object, but also keeps a reference to be able to return the same instance if the object is requested again (unless the definition is UnShared).

A container can only build objects defined in the same scope (scopes documentation). If the container is asked to retrieve an object that belongs to a different scope. It forwards the request to its parent.

There are three methods to retrieve an object: Get, SafeGet and Fill.

Get returns an interface that can be cast afterward. If the object can not be created, the Get function panics.

// Retrieve the object from the definition (recommended)

o1 := ctn.Get(MyObjectDef).(*MyObject)

// Or from its name (which is slower)

o2 := ctn.Get("my-object").(*MyObject)

// Or from its type (even slower)

o3 := ctn.Get(reflect.typeOf((*MyObject)(nil))).(*MyObject)

// o1 == o2 == o3Get is an easy way to retrieve an object. The problem is that it can panic. If it is a problem for you, you can use SafeGet. Instead of panicking, it returns an error.

objectInterface, err := ctn.SafeGet(MyObjectDef)

// You still need to cast the interface.

object, ok := objectInterface.(*MyObject)

// SafeGet can also be called with a definition name or type.

objectInterface, err = ctn.SafeGet("my-object")

objectInterface, err = ctn.SafeGet(reflect.typeOf((*MyObject)(nil)))The third method to retrieve an object is Fill. It returns an error if something goes wrong like SafeGet, but it may be more practical in some situations. It uses reflection to fill the given object. Using reflection makes it slower than SafeGet.

var object *MyObject

err := ctn.Fill(MyObjectDef, &object)

// Fill can also be called with a definition name or type.

err = ctn.Fill("my-object", &object)

err = ctn.Fill(reflect.typeOf((*MyObject)(nil)), &object)Definitions can also have a scope. They can be useful in request-based applications, such as a web application.

MyObjectDef := &di.Def{

Scope: di.Request,

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}The available scopes are defined when the Builder is created:

builder, err := di.NewEnhancedBuilder(di.App, di.Request)Scopes are defined from the most generic to the most specific (eg: App ≻ Request ≻ SubRequest). If no scope is given to NewEnhancedBuilder, the builder is created with the three default scopes: di.App, di.Request and di.SubRequest. These scopes should be enough almost all the time.

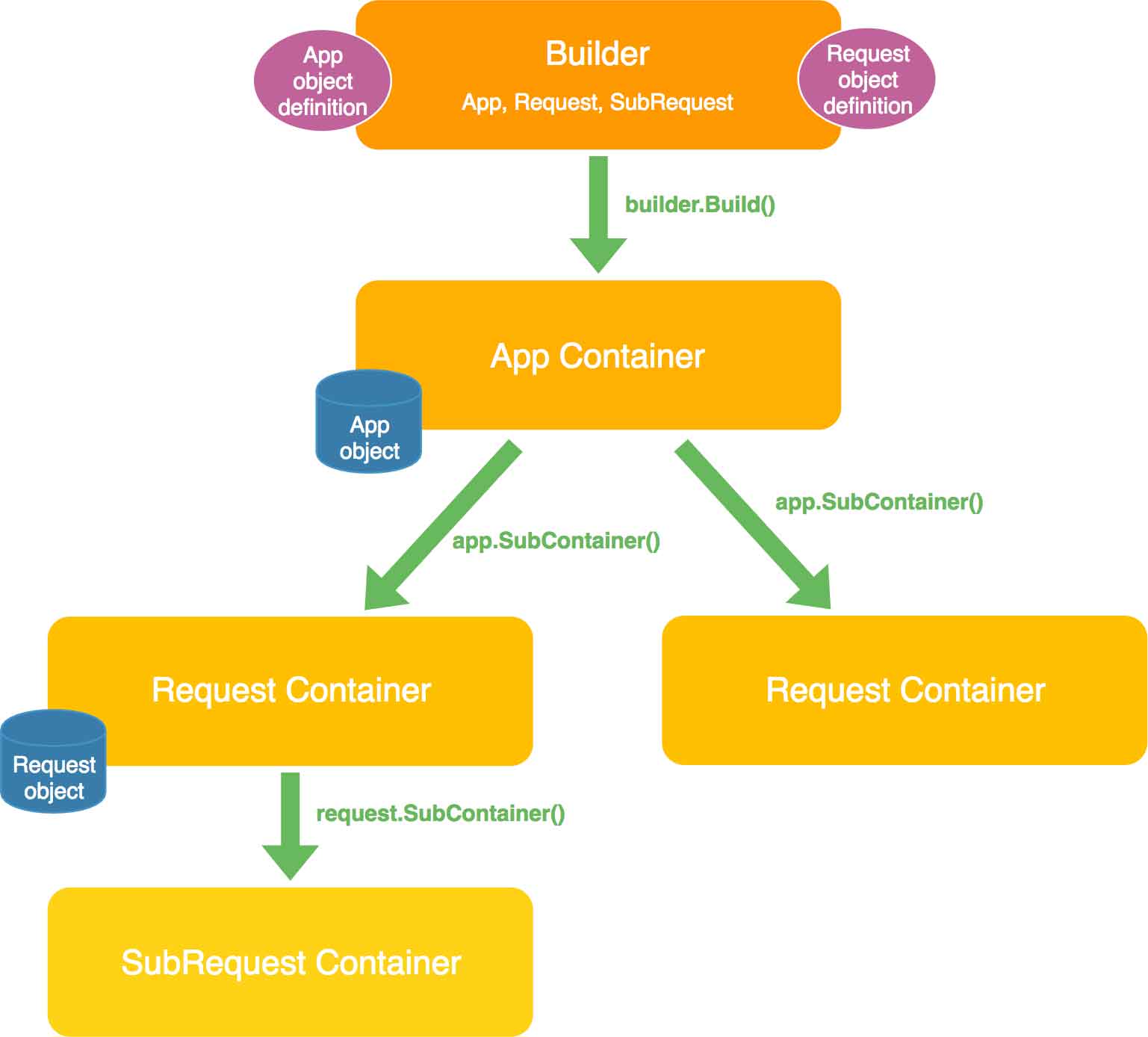

The containers belong to one of these scopes. A container may have a parent in a more generic scope and children in a more specific scope. The builder generates a container in the most generic scope. Then the container can generate children in the next scope thanks to the SubContainer method.

A container is only able to build objects defined in its own scope, but it can retrieve objects in a more generic scope thanks to its parent. For example, a Request container can retrieve an App object, but an App container can not retrieve a Request object.

If a definition does not have a scope, the most generic scope will be used.

// Create a Builder with the default scopes (App, Request, SubRequest).

builder, err := di.NewEnhancedBuilder()

// Define an object in the App scope.

AppDef := di.Def{

Scope: di.App, // this line is optional, di.App is the default scope

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

err = builder.Add(AppDef)

// Define an object in the Request scope.

RequestDef := di.Def{

Scope: di.Request,

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

err = builder.Add(RequestDef)

// Build creates a Container in the most generic scope (App).

app, err := builder.Build()

// The App Container can create sub-containers in the Request scope.

req1, err := app.SubContainer()

req2, err := app.SubContainer()

// app-object can be retrieved from the three containers.

// The retrieved objects are the same: o1 == o2 == o3.

// The object is stored in app.

o1 := app.Get(AppDef).(*MyObject)

o2 := req1.Get(AppDef).(*MyObject)

o3 := req2.Get(AppDef).(*MyObject)

// request-object can only be retrieved from req1 and req2.

// The retrieved objects are not the same: o4 != o5.

// o4 is stored in req1, and o5 is stored in req2.

o4 := req1.Get(RequestDef).(*MyObject)

o5 := req2.Get(RequestDef).(*MyObject)More graphically, the containers could be represented like this:

The App container can only get the App object. A Request container or a SubRequest container can get either the App object or the Request object, possibly by using their parent. The objects are built and stored in containers that have the same scope. They are only created when they are requested.

If an object depends on other objects defined in the container, the scopes of the dependencies must be either equal or more generic compared to the object scope.

For example the following definitions are not valid:

di.Def{

Name: "request-object",

Scope: di.Request,

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

}

di.Def{

Name: "object-with-dependency",

Scope: di.App, // NOT ALLOWED !!! should be di.Request or di.SubRequest

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &ObjectWithDependency{

Object: ctn.Get("request-object").(*MyObject),

}, nil

},

}When you no longer need a container, you can delete it.

err := ctn.Delete()Delete closes all the objects stored in the Container by calling their Close function.

Deleting the container makes it unusable, but it frees its memory. So you probably should use it even if none of your definitions have a Close function.

If there are dependencies between definitions, the Close functions are called in the right order (dependencies after).

Deleting containers is very useful when using scopes. You will want to delete the Request container at the end of each request. The App container will still be usable.

There are two delete methods: Delete and DeleteWithSubContainers

DeleteWithSubContainers deletes the children of the Container and then the Container. It does this right away. Delete is a softer approach. It does not delete the children of the Container. Actually it does not delete the Container as long as it still has a child alive. So you have to call Delete on all the children. The parent Container will be deleted when Delete is called on the last child.

You probably want to use Delete and close the children manually. DeleteWithSubContainers can cause errors if the parent is deleted while its children are still used.

The Get, SafeGet and Fill functions can retrieve an object defined in the same scope or a more generic one. If you need an object defined in a more specific scope, you need to create a sub-container to retrieve it. For example, an App container can not create a Request object. A Request container should be created to retrieve the Request object. It is logical but not always very practical.

UnscopedGet, UnscopedSafeGet and UnscopedFill work like Get, SafeGet and Fill but can retrieve objects defined in a more generic scope. To do so, they generate sub-containers that can only be accessed internally by these three methods. To remove these containers without deleting the current container, you can call the Clean method.

Build function. In this case, circular definitions are not detected. If you do this, you take the risk of having an infinite loop in your code when building an object.

builder, err := di.NewEnhancedBuilder()

err = builder.Add(di.Def{

Name: "request-object",

Scope: di.Request,

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

return &MyObject{}, nil

},

Close: func(obj interface{}) error {

return obj.(*MyObject).Close()

},

})

app, err := builder.Build()

// app can retrieve a request-object with unscoped methods.

obj := app.UnscopedGet("request-object").(*MyObject)

// Once the objects created with unscoped methods are no longer used, you can call the Clean method.

// In this case, the Close function will be called on the object.

err = app.Clean()DI includes some elements to ease its integration into web applications.

The HTTPMiddleware function can be used to inject a container in an http.Request.

// Create an App container.

builder, err := di.NewEnhancedBuilder()

err = builder.Add(/* some definitions */)

app, err := builder.Build()

handlerWithDiMiddleware := di.HTTPMiddleware(handler, app, func(msg string) {

logger.Error(msg) // Use your own logger here, it is used to log container deletion errors.

})For each http.Request, a sub-container of the app container is created. It is deleted at the end of the http request.

The container can be used in the handler:

handler := func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Retrieve the Request container with the C function.

ctn := di.C(r)

obj := ctn.Get("object").(*MyObject)

// There is also a shortcut to do that.

obj := di.Get(r, "object").(*MyObject)

}The handler and the middleware can panic. Do not forget to use another middleware to recover from the panic and log the errors.

The sarulabs/di-example repository is a good example to understand how DI can be used in a web application.

More explanations about this repository can be found in this blog post:

If you do not have time to check this repository, here is a shorter example that does not use the HTTP helpers. It does not handle the errors to be more concise.

package main

import (

"context"

"database/sql"

"net/http"

"github.com/sarulabs/di/v2"

_ "github.com/go-sql-driver/mysql"

)

var MysqlPoolDef = &di.Def{

// Define the connection pool in the App scope.

// There will be one for the whole application.

Name: "mysql-pool",

Scope: di.App,

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

db, err := sql.Open("mysql", "user:password@/")

db.SetMaxOpenConns(1)

return db, err

},

Close: func(obj interface{}) error {

return obj.(*sql.DB).Close()

},

}

var MySqlDef = &di.Def{

// Define the connection in the Request scope.

// Each request will use its own connection.

Name: "mysql",

Scope: di.Request,

Build: func(ctn di.Container) (interface{}, error) {

pool := ctn.Get("mysql-pool").(*sql.DB)

return pool.Conn(context.Background())

},

Close: func(obj interface{}) error {

return obj.(*sql.Conn).Close()

},

}

func main() {

builder, _ := di.NewEnhancedBuilder()

builder.Add(MysqlPoolDef)

builder.Add(MySqlDef)

app, _ := builder.Build()

defer app.Delete()

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Create a request and delete it once it has been handled.

// Deleting the request will close the connection.

request, _ := app.SubContainer()

defer request.Delete()

handler(w, r, request)

})

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, ctn di.Container) {

// Retrieve the connection.

conn := ctn.Get(MySqlDef).(*sql.Conn)

var variable, value string

row := conn.QueryRowContext(context.Background(), "SHOW STATUS WHERE `variable_name` = 'Threads_connected'")

row.Scan(&variable, &value)

// Display how many connections are opened.

// As the connection is closed when the request is deleted,

// the value should not be higher than the number set with db.SetMaxOpenConns(1).

w.Write([]byte(variable + ": " + value))

}Retrieving an object from a container will always be slower than directly using a variable. That being said, DI tries to minimize the cost of using containers.

The Get method accepts different types as parameters. If possible you should use a di.Def as it is the fastest.

Even if it is a bit slower (additional lookup in a map[string]int to get the associated di.Def), using the name of the definition is still pretty fast and is an acceptable choice in most applications.

When using shared objects (which is the default with Def.Unshared set to false), the first call to the Get method will create the object. After its creation, it must be stored in the container. This can be relatively slow as to avoid data races it uses a mutex and blocks the container for a brief moment.

It should not be an issue in most applications. But if you need the object retrieval to be really fast, you need to call the Get method before the critical path in your application to preload the container. After that, the next calls to Get will be much faster.

Unshared objects may also be stored in the container if they have a Close function (otherwise they could not closed). So retrieving these objects is slow as it blocks the container with a mutex. So if you are looking to improve the performance of your container, avoid using Unshared definitions with a Close function.

Definitions with a lot of dependencies at several levels (dependencies having dependencies) are likely to be slow to build compared to creating the object manually.