-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 2

Design of XMMS2

For the older version of this page, see Design of XMMS2/pre-DrEvil.

What is played by XMMS2. This can be a file (mp3, ogg vorbis, WAVE) or network stream (mp3 streaming over HTTP)

A library containing metadata read from streams played by XMMS2. Clients may modify or add to this metadata.

The XMMS2 daemon. Referred to interchangeably as 'server' and 'daemon' here.

The XMMS2 system is split into two main components: the server, and multiple clients. There are a few reasons for this architectural model:

- It's the ultimate form of loose coupling between the part responsible for playing audio and the part controlling the former part. Therefore, users aren't restricted simply to modifying 'skins', they can interact with the player in various other ways.

- There isn't a 1:1 mapping between the player and the controller interface - the user can run as many or as few interfaces as he chooses.

An XMMS2 client provides an interface (graphical, command line, or otherwise) to:

- Allow the user to control playback (play, pause, stop)

- Allow the user to choose what to play (next, previous, add/remove to/from playlist)

- Manage a collection of audio streams (via the medialib)

- Alter the server's configuration

- Display visualisation animations

A client is not restricted to these functions - it may also do things unrelated to XMMS2 itself, such as connecting to portable digital audio players, etc

The XMMS2 daemon (xmms2d):

- Allows clients to connect to it via IPC sockets (TCP or UNIX sockets)

- Responds to client commands

- Maintains a playlist of streams to play

- Maintains metadata stored in the medialib

- Reads and decodes encoded audio data from streams before (optionally) applying effects and outputting the result to an audio device.

- Responds to configuration changes

- Provides visualisation data about the current audio data being played

Despite being written in C, the daemon's designed to be composed of a number of discrete 'objects'. This has more to do with modularisation than with object orientation, and is achieved in two ways:

- The code is organised in files such as output.c and output.h for the 'Output' object. The 'object' itself is defined as a struct, and functions to manipulate this struct are defined in the appropriate C file. From an OO perspective, the struct can be said to contain the object's attributes, and the functions to be the class methods. The API naming convention is similar to Glib's: _.

- Basic object services are provided by object.c and object.h. These services include:

- Object creation

- Reference counting

- Object destruction

- Signal emission (similar to Glib's signals) - responsible for propagating state changes to the IPC layer (see below) so that notification messages may be sent to clients.

The daemon maintains its configuration in an XML file read on startup and saved on shutdown. The configuration file itself is serialised and deserialised using Glib's GNode and GMarkupParser. In memory, the configuration data is maintained as a hashtable of keys and associated values and is accessed by all parts of the daemon itself. The configuration API is also exposed to clients via the IPC layer so that configuration values may be read and modified by client applications.

The part of the daemon responsible for serialising and deserialising messages to/from clients. Other parts of the daemon register 'IPC signals' which extend the signal service provided by object.c - whenever the objects then emit registered signals, this layer marshals an appropriate notification message and sends it to connected clients that have requested the particular notification type. (see Middleware) Parts of the daemon also register 'IPC commands' that may be activated by clients - once a message arrives, it is deserialised and the specified command is executed in the daemon. As far as implementation goes, the IPC layer listens for client connections using a GSource attached to the daemon's GMainLoop and starts a thread to service each client connection accepted.

Playback is performed in this order: transport, decoding, effects, visualisation, and finally, output. For releases up to DrDolittle, the daemon itself provided a plugin interface for each stage, so that the real work was done by a number of plugins, much like gstreamer. The main components involved in this process - transport, decoding, output - were run in their own separate thread. Following the release of DrDolittle, the internal processing stages were generalised so as to provide a 'chain' of 'transformation' plugins whose job it is to transform data from one format to another. The order of operations remains the same (transport, decoding, etc), however, the explicit layers and plugin APIs have been merged into a single 'transform' phase. For more information about this process, see Transforms.

The transport stage simply aims to read a stream from a given URL. Once a plugin is found for an appropriate URL type, the plugin is initialised and starts reading the stream. The data is buffered and the stream header used to determine the next plugin to use in the processing stream.

The decoder stage reads data buffered by the transport layer and passes it through appropriate decoder plugins so as to produce PCM audio data. (See Transforms for details about how this happens.)

Once audio data has been decoded from the stream, effects can be applied - this includes equalisation. In practice, the application of audio effects is done just after the decoding stage.

The visualisation component of xmms2d performs a fast fourier transform (fft) on the decoded audio data being sent to the output device. (This stage occurs just after the application of effects) The result of this operation can then be streamed as a 'signal' to clients, if requested. Clients may then use this data stream to display animations so the user can 'visualise' the audio.

The final stage of the playback process is the output to a certain audio device, such as ALSA, OSS, JACK, etc. In practice, it's the Output object that's responsible for starting the playback process itself. It fetches the current playlist item, creates a transform chain to transport and decode the stream, begins playback, and reads buffered data from the transform chain and sends it to the audio device.

The playlist in xmms2d is simply an ordered list of medialib IDs of the streams to be played. Storing only the ID numbers (32 bit unsigned integers) allows the playlist itself to have a small memory footprint and thus allow it to contain a large number of entries without significantly affecting performance.

see main article: The Medialib

The Medialib (media library) is where XMMS2 stores metadata about files as it plays them. It is implemented using an sqlite database, so queries and data updates are all performed using standard SQL queries. Having a media library allows XMMS2 to 'remember' the songs it has played, and thus allows users to easily re-create their favourite playlists.

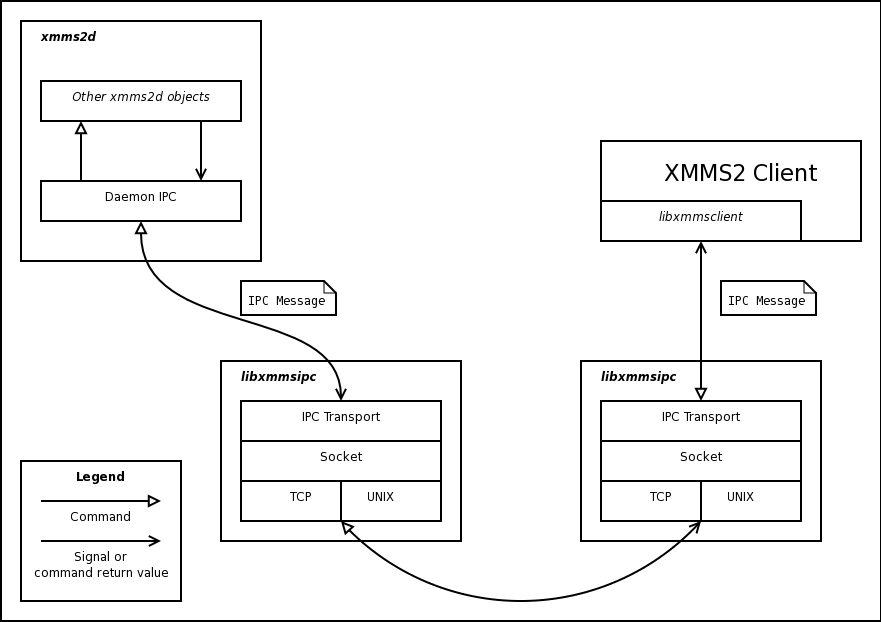

Communication between the daemon and clients is done via a couple of middleware libraries, in contrast to the MPD approach, where clients use a plaintext protocol over a TCP connection. The rationale for the middleware approach is to reduce the common overhead incurred by all clients when it comes to parsing plaintext when handling the protocol. Two libraries provide a higher level interface to client developers:

- libxmmsipc - Abstracts the lower level IPC methods (UNIX and TCP sockets) and provides a 'transport' layer for exchanging messages.

- libxmmsclient - (The client library) Provides an interface for clients to use to communicate with the daemon and handles the task of marshalling and unmarshalling messages over the IPC transport layer.

As explained above, the client library mainly provides an interface to clients and deals with the following concepts:

An XMMS2 client may communicate with the daemon in one of two modes:

The client requests a command, waits for the result, then continues processing. This mode suits some interactive clients, such as shell-type clients.

The client requests one or more commands, sets notifiers for the results of those commands, then enters a mainloop where it makes sure to push data to, or read data from, the daemon when the IPC file descriptor is ready. As data comes in (in the form of results or signals), the client library executes the result notifiers previously set - these notifiers may do actions such as updating graphical widgets, and so on. This mode especially suits graphical clients, where the process can handle events from multiple sources at various times in an asynchronous manner.

It is not a good idea to mix the two modes of communication on the same connection. If the two modes are mixed, results from commands may trigger their associated callbacks in an inappropriate or unpredictable sequence.

A command is an action requested from the daemon by a client. It can be something like 'start playback', 'add url to playlist', etc. Every command returns a result.

A result is data returned from a command - it is a generic structure that can contain various data types (int, uint, string, list, dict, propdict - much like Glib's GValue type), as well as fields to specify whether an error occurred during the execution of a command.

A signal is a type of notification which a client can request from the daemon to peek on some aspect of the daemon's state. A signal is requested much like a command, and returns a result. In fact, signals in synchronous clients work just like commands. You can wait on the result of a signal and get a value from the returned result just like any command. Signals used in asynchronous clients are different in that they must be restarted after each time the notifier is called in order to be called again. Thus, the client using signals determines the frequency at which a signal is called. In practice, signals are good for things like updating the current playback position of a song, where a client may want to be updated every second.

Similar to signals, broadcasts are a notification requested by the client to stay updated with the daemon. However, broadcasts differ from signals in that they can be called any arbitrary number of times and don't need restarting. Also unlike signals, broadcasts are called when the daemon's state changes, which means it is less like peeking in on the state since broadcasts are called as events happen. Synchronous clients can use broadcasts, however it is not common practice as waiting on a broadcast result means waiting for a specific event to occur in the daemon, which can take any arbitrary length of time. Some broadcasts are never called during the life of a client, so it generally makes more sense to use broadcasts in asynchronous clients, so that notifiers are called when an event occurs. In practice, broadcasts are useful for things like keeping playlists synchronized.

XMMS2 clients may be written in a variety of languages, using libxmmsclient and its associated bindings. There are subtle differences in the API offered by the bindings for various languages. For more information, please see Writing XMMS2 Clients; for useful code examples, see the xmms2-tutorial Git repository. xmms2-tutorial includes example client code in C, C++, Ruby, Python, Java, and Perl.

Content is available under GNU Free Documentation License 1.2 unless otherwise noted.

- Community

- Development